Snowy Construction Camp Capers

'Construction Camp Capers' by Betty Mattner AM (1999) - Life in the Camps on the Snowy Scheme 1958-1967

Introduction

Construction Camp Capers is a story about ‘modern-day’ pioneering women in Australia. Women who helped build the ‘Snowy Scheme’ not on construction teams but in construction camps. Moving with their husbands to the remote high country they built communities from nothing.

Many of the ‘Snowy’ women had young families or were starting families in the isolated communities set amongst the snow gum trees. Separated from close knit relatives and many times from their husbands, they were often alone during times of crisis and celebration. They endured the harshest of weather and coped without services and facilities taken for granted by women in the cities.

Review

Construction Camp Capers is a colourful memoir about Betty’s (‘Bet’s) life in the ‘Snowy’ camps from 1958 to 1967. It’s a heart-warming book about people coming together to help achieve one of the world’s greatest engineering feats in one of nature’s harshest environments. Importantly, it’s a recording of a moment in history when Australia became a melting pot of cultures. Men arrived from all parts of Europe, Scandinavia, Ireland, Great Britain, New Zealand, America and Canada but “integration was easy and embraced without any consciousness”. More importantly, it’s about women. Women reaching out, helping each other, being resourceful, creating safe and nurturing places for their children and themselves.

The book covers life in three camps, Tantangara (1958-1961), Island Bend (1961-1965) and Jindabyne 1965-1967). Each camp had its own unique character, challenges, hardships, joys and sorrows. Bet writes in an engaging style and captures the mood and moment. Lots of moments. Bet’s tales are mostly funny. I laughed most of the way through. How could you not laugh at the story about one of the wives, Edie, who set up her sewing machine in the front yard during summer and sewed in her bikini. The small book has a movie written all over it.

Starting a New Life

Bet’s story starts when she and husband Dick, a mining engineer, leave South Australia in September 1958 with their young son Paul, to start a ‘new and exciting life’. Dick had been appointed Tunnel Engineer on the Murrumbidgee-Eucumbene project. Their first taste of ‘Snowy’ life was in the construction camp at Tantangara.

She writes how her ‘new and exciting life’ started with tears of despair. After driving into the camp and passing the men’s barracks housing 650 single men, the Utah trailer park, caravan park and Utah houses sitting on blocks with no garages, fences or gardens, Bet wrote:

“The camp was so bleak and bare with dirt roads, no facilities and houses looking like they were just dumped in the bush. It all seemed so forlorn and godforsaken. I thought ‘My God, what am I doing here’. Worse was to come.

As we turned the corner at the end of the street, Dick said ‘That’s our house on the left hand block’. I just sat in the car and stared. Our house on timber posts, without garage or fences, had been erected on a sloping block with the front door six feet off the ground and there were no steps! Dick sensing my dismay, hurried to find a box to climb on to reach the front door. After turning the key, the door would open only a few inches. My spirits fell further. The baby was tired and hungry and there was nowhere else to stay. We then tried the back door which was only two feet off the ground with a timber box already in place and gained entry.

Once inside, we found the refrigerator had been pushed against the door and our few bits of furniture dumped in the lounge room. Apparently, the removalists had been in a hurry to leave. I felt the same way.

The Snowy Mountain Authority (SMA) workmen and the removalists had trampled mud and dirt everywhere. The bath and hand basin were half full of dirty water and cigarette butts. The kitchen sink and laundry tub were in the same condition. It was all too much. I started to cry and said, ‘Enough is enough’. I’m not staying here! I’m going back to my parents in Cootamundra.’ However, Dick convinced me things would look better in the morning, so we set about unloading the car and shifting our bits of furniture into the various rooms.”

Housing provided by the SMA was basic. The houses were used and reused. As soon as a camp wound up, the houses were moved to other locations taking their history and stories with them. Bet and Dick’s first house came from the ‘Happy Jack’ Construction Camp between Eucumbene Dam and Tumut Pond Dam which someone recognised as their previous house. Their house in Jindabyne was the former office in Tantangara, “two sections of which had fallen off the low-loaders on its way out of Island Bend, spending the winter in the snow”.

While husbands worked six days (and some nights) a week, wives turned their houses into homes by adding their own personal touches with curtains, paint, floor coverings and gardens. The wild lupins in the Snowy Mountains today are a reminder of the ‘Snowy’ women.

Women United

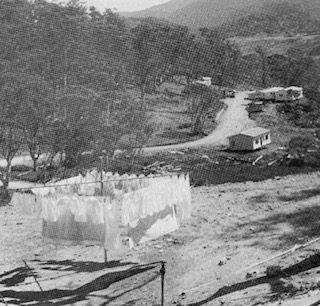

The isolation, Bet said helped bring the women together and broke down barriers. They rarely drove anywhere alone and communal shopping trips were organised to share the driving and child care. There was no pre-school, baby health centre, sporting facilities, fire brigade or entertainment. Most women made their own clothes and their children’s. Zippers, buttons and tapes were saved from the old clothes and then reused. As more and more babies were born there were more and more clotheslines of white nappies fluttering in the wilderness.

The American company Utah – the contractors building Tantangara Dam and the 10-mile diversion tunnel from the dam to Providence Portal on the Eucumbene River – helped improve life in the camp by establishing a supermarket and a community hall. It didn’t take long for the Utah personnel and the SMA personnel and families to get to know each other and start socialising and supporting each other. There were plenty of parties, shower teas, dances, balls and celebrations. Bet said:

“Despite the isolation, we were all clothes conscious. When invited out for morning or afternoon tea or for drinks at night, we always put on our best clothes and wore flatties, carrying our high heeled shoes in a bag to put on when we arrived. Otherwise, the camp would have been full of women with broken legs or ankles or ruined shoes.”

Winters were harsh and trying to keep warm in uninsulated portable houses was a major problem for families. Winter brought with it snow showers, snow storms, blizzards, hazardous roads, frozen water pipes and gumboots. Summer brought March flies, alpine daisies, wildflowers and glittering mountain streams.

There was a Primary School at Tantangara with over thirty children and Bet soon found herself elected onto the P & C and was given lots of jobs because she only had one child! It wasn’t long, however, before two more babies arrived on the scene, Christopher in 1960 and then James in 1962. She ended up remaining with the Association until March 1981 and was made a life member in 1979.

In 1959 Tantangara camp women were commandeered to form the All Women Tantangara Fire Brigade known as the ‘Fire Belles’. If a fire broke out the ‘Fire Belles’ had to deal with it until the fire engine arrived from seven miles away. Only a woman could organise a fire duty roster so perfectly, where women on duty left their children with the unrostered mothers. Their training wasn’t wasted because in 1961 they managed to contain a fire burning towards the SMA offices until the fire engine arrived.

Women learned to master their circumstances on the ’Snowy’ rather than be mastered by them. They set up a Ladies Association and lobbied the powers-that-be for finance and buildings to set up pre-schools and Baby Health Centres. Fundraising events from fashion parades to cabarets were organised to purchase school equipment. Each event has a story attached which Bet recalls with great humour.

Her story starts with tears and it ends in tears. In June 1967 after parts of old Jindabyne were drowned Bet and Dick were notified, they had been allocated a house in Cooma North. Bet realised that her construction camp years had come to an end. She wrote:

“My life would never be the same again. I knew I would miss the mountains, life in construction camps, and the close bonds formed with friends in the Regions. It was the end of an era. After shedding a few tears, it was now time for us to pack up the car with the last few things, put in the three boys and head for Cooma; only a short distance but a whole world away.”

I loved reading this book. I’ve had it for twenty years but somehow it got lost in the bookshelves and moves. I found it again just recently and sat down with a cuppa and started reading. I couldn’t put it down. The story was so engaging, written with warmth and authenticity. I now want to go and look for the poplars and lupins at Tantangara, a sure sign of where Bet and Dick once lived with the other wonderful people of the ‘Snowy’ construction camp era.

My family lived at Tantangara settlement and my father managed Nungar camp during the period that Betty Mattner was there.

I would be interested in whether Betty knew them.

Could you pass this reply to Betty?

She may contact me via email if she so wishes.

Cheers.

Hi Marshall

Great to hear. I’ll certainly let Betty know and pass on your email. Thanks for your reply.

Regards

Sue