There’s nothing like watching Banjo Paterson’s poem come to life with footage from the 1982 movie ‘The Man from Snowy River’. Listen to the poem while watching the daring brumby chase unfold.

Introduction

The Man from Snowy River is one of the most popular poems in Australia’s history. It may not be recited as much now but it is embedded in our folklore and in the imaginations of many. People still ask; “Who is The Man from Snowy River[i]?” and 129 years after the legendary verse was first published in ‘The Bulletin’ in 1890, the issue is still one of intense debate and speculation.

The Undying Question

The question of The Man’s identity has fascinated and occupied the minds of countless Australians from the city and bush, high country, low country, even the coast. Some people are adamant in their thinking of who The Man is using ‘evidence’ of stories handed down through families and friends of families and friends of friends. Even a postscript on a letter was used to lay claim to The Man.[ii]

The question has been posed in books, articles and television programs. W.F Refshauge in his thoroughly researched and engaging book ‘Searching for the Man from Snowy River’ didn’t come to a definitive conclusion. However, he certainly managed a comprehensive analysis of a field of candidates by testing them against Paterson’s criteria and coming up with a most likely contender, but not a definite one.[iii]

By leaving his hero’s identity ‘up in the air’ Paterson ensured the question will never die because it can never be answered. This is despite an attempt late in his life to clear up the question by saying that The Man was imaginary and not based on any one individual.[iv] This didn’t stop the speculation. Many believe they know the answer and defend their candidate to the hilt. Many probably believe he is ‘Jim Craig’, played by Tom Burlinson in the 1982 movie ‘The Man from Snowy River.’

Proof the Poem is Still Alive

I recently experienced the force of the undying question. Staying on Victoria’s Surf Coast the subject of the Upper Murray and Corryong came up with some locals over drinks. It didn’t take long for the subject to turn to the Man from Snowy River. 74 year old Patrick, who reminisced about the Man from Snowy River Festival in Corryong, said it was Jack Riley for sure and for certain. Pat’s decisive statement showed me that Paterson’s poem is still alive, still a topic of conversation and still controversial when it comes to the question of; Who is The Man?

There’s no doubt that Paterson himself, remains embedded in the hearts of many Australians with his verses and stories. I asked Hector, my 92 year old friend who was hosting the drinks, if he liked Banjo Paterson and he said: “Of course. I named my Kelpie, after him!” But there is doubt about the identity of the real Man from Snowy River. If indeed he has a singular identity.

Rides Became Legendary and the Horsemen Legends

Momentous rides by individuals were forever remembered by mountain men and women who would stake a claim on a mountain horseman near them as being The Man. Riding feats were often the talk of the town between men at the pub and women at a tea party. Horse talk in the latter part of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century was like car talk today. A horse might have been the most valuable asset a person had and riding a horse an integral part of their life – certainly a means of transportation or crucial to their livelihood. Cleaning up wild horses was a common activity in the bush not only for work purposes, but early settlers regarded it as a sport. As far as our pioneering property owners were concerned wild horses were pests to be dealt with.

Wild Horses

Paterson provides us with the best explanation of why Australia has wild horses in one of his talks in the 1930s. The original mobs of wild horses formed after they got away or were dropped at the wayside by original settlers and explorers. Later on, horses might get away from properties in outlying areas due to damaged or broken down fences and form more mobs. Old stallions not liking young colts hanging about and posing a leadership challenge, drove them out of the mob and with a few mares in tow another mob started. Horses left by owners to feed on township commons were another boon to wild mobs. These horses would often move on if the grass got too low or they wanted a change. If owners put off the task of retrieving their horses, which many did, before they ventured too far away their horse would be off to join the wild bush brumbies.

He said:

“So the stallion would establish himself up in the hills with a few mares and, when the spring came on, he would come down to the common and drive off any mares that were there and add them to his harem. Incidentally, he might murder any gelding that tried to go with the mares, for a stallion is a very good imitation of a pirate king when he gets the chance to run things his own way.”

“Sometimes riding through the bush, you would catch sight of a mob of them and then off they’d go full split, their hoofs sounding like a cavalry charge, manes and tails flying, the stallion driving the mares and foals in front of him and looking over his shoulder at you as much as to say that for two pins he’d come back and take a fall for you.”

“Sometimes there would be casual mobs of dry mares and geldings without any stallion and, as these had no foals to delay them, they would set the best rider in Australia a task to get them out of that rough country where they had no weight on their backs and knew every foot of the going. In some rough country stations in the early days, the wild horses got to be as big a plague as the wallabies and rabbits were in later times, and they used to put up trap yards with wings running out into the bush and the riders would start a mob going and would try to go with it fast enough to keep on the wings of the mob and crack the whips and send the mob into the trap yard. Then they would shoot them just like vermin. It seems a terrible thing to us nowadays to think of shooting horses wholesale … but it had to be done for, if they didn’t get rid of the horses, the horses would get rid of them.”[v]

It was rather pointless trying to break in these feral horses and selling them as Paterson explains:

“The horse shooting days were pretty well done when I came into the business, and we used to run them in with the mistaken idea of breaking them in and making some money out of them. Half a dozen of us would go out and we’d ride half a dozen good horses blind getting the mob in. Then the crack riders amongst us would pick out a horse each and start to break it in. By the time that it had kicked every dog in the place, or those that it had missed it had kicked others twice for, by the time that it had broken every bridle and rolled in every saddle on the place and by the time that every rider had been run against at least one tree in every paddock, then it was saleable at about thirty bob if anyone could be found fool enough to buy it. You see they were mostly old, and breaking in old horses, especially when they have been wild, is like teaching an old cannibal to be a vegetarian.”

The Poem had Pride of Place on Many Occasions

For decades after it was penned by Patterson the stirring poem was recited at concerts, celebrations, around campfires and in elocution competitions. It’s not the easiest poem to recite, but if done with “consummate skill” as Mr J Morrison did at the Yackandandah Presbyterian Church’s Anniversary in November 1897 it can “make even the dullest imagination follow … with bated breath.”[vi]

People couldn’t get enough of the poem. It was even recited on the top of Mount Kosciusko, the highest peak in Australia. Writing as ‘The Tourist’ in the Sydney Mail in 1894 W.L.E. wrote how he and his friends hired Mr Spencer and set out on horseback from Jindabyne with the aim of seeing the sun rise from the top of Mount Kosciusko. Around the campfire on Ramshead Range, after dinner and songs the poem was recited. W.L.E wrote that the reciter, “who had made a special study of this word picture of a wild horse hunt … delivered it with all the pathos, force, vigour, and realism that characterise the poem.”

The poem came to life for the party as they rode through the same country where mobs of wild horses were seen fleeing in the distance and the “instinct and knowledge” of mountain men like Spencer and their horses were essential to avoid sinking in the “green deceitful quagmires or bogs” hidden naturally in the landscape. (Sydney Mail, 30 March 1895)[vii]

Corryong’s Jack Riley

‘The Man’ question has created division within and between communities. Corryong for instance has claimed exclusive rights to The Man and the township holds an annual bush festival in his name. Thanks largely to the efforts of Thomas (Tom) Mitchell (1906-1984), Jack Riley was crowned The Man. Mitchell genuinely believed in the Riley legend. A legend probably formed from stories passed down by his father Walter, who accompanied Paterson on a camping trip to Tom Groggin station where he met and yarned with Jack Riley.

Riley’s Grave

When he was Shire President of the Upper Murray council between 1945-1947, Mitchell turned Jack Riley’s grave, unmarked for forty years, into a local shrine by erecting a headstone made from “a rough-hewn semi-circular piece of granite that had been intended for the new bridge at Jingellic years before, but not used,” along with “a small plinth, suitably inscribed, mounted on this tough granite.”[viii]

Keeping the Riley Legend Alive by Changing the Story

To add further credence to his belief that Jack was The Man, Tom Mitchell wrote in the Corryong Courier in 1962 about meeting Paterson socially in 1936 and asking him who was The Man. Paterson reportedly said that “he was to a large extent imaginary – but was woven around Jack Riley.” [ix] The “woven around” eventually became a singular and definite “Jack Riley” in 1983 in a letter to the Royal Australian Historical Society where Mitchell wrote: “I asked ‘Banjo’ point blank who was the man from Snowy River, and he replied ‘Jack Riley.’”[x]

The Man from Snowy River Festival

In the 1960s Mitchell shared his idea that the Man from Snowy River could put Corryong on the map just as the Dog on the Tuckerbox had put Gundagai on the map.[xi] It was a clever idea and it did put Corryong on the map. The annual ‘Man From Snowy River Bush Festival’ is a testament to Mitchell’s enthusiasm and determination. The festival celebrates Australia’s skilled horsemanship, bush heritage, culture and spirit. But it also keeps the legend of Jack Riley as The Man alive.

Since 1995 thousands of people gather each year in Corryong with its mountainous backdrop to watch and honour Australia’s unique bush horsemen. It will be an extra special gathering in 2020 as it marks the 25th anniversary of the event. Corryong has much to thank Tom Mitchell for his enduring legacy and for keeping the Riley legend intact despite his wife Elyne Mitchell, famous writer of the ‘Silver Brumby’ books, believing The Man to be a “composite character.”[xii]

Did Jack Really Have the Credentials?

It didn’t seem to matter to Tom Mitchell that Jack Riley didn’t live near the Snowy River but lived at Tom Groggin Station on the Murray River. Or that he wasn’t a stripling when Paterson wrote the poem but a grown man. Or that he wasn’t mountain bred but born in Ireland. Or that he immigrated to Australia at around 13 years and most likely worked in an Omeo store with his sister when mountain bred boys were out on their nags. Some say he worked as a tailor. What this all seems to suggest is that Jack wasn’t born in the saddle.

Jack obviously learned to ride like most young men did in the bush because for the early part of his adult life he worked as a casual stockman. He became a permanent station hand on John Pierce’s ‘Greg Greg’ station in 1884 when he was 43 years old[xiii] and around five years later in 1899 he acquired (or dummied) a piece of Pierce’s Tom Groggin run. During that period Tom Groggin was the summer grazing place for Pierce’s cattle. There’s no doubt he probably developed into a competent bush horseman over the years and no doubt he developed riding skills, but nothing “uniformly described in glowing terms.”[xiv] (Refshauge, 2012). Pat Daley, who had lived at both Towong and Brigenbrong stations for 72 years said he’d never heard “Jack Riley as a champion bush rider.”[xv]

The Monaro – Most Likely Home of The Man

‘Banjo’ might have met Jack Riley with Tom Mitchell on one of his High Country visits, but he also enjoyed visiting Monaro pastoral properties and stayed on many occasions at Bolaro Station, formerly Rosedale and home to the McKeahnie family, which lies north of Adaminaby on the Murrumbidgee River.[xvi] The Monaro is the most likely area from where The Man originated. Cooma citizens seem to think so with their statue in Centennial Park commemorating Paterson and his poem. I’m afraid I don’t think the statue does, the Poet, the Horse or The Man justice. Others however, probably think differently.

A Long Line of Candidates and Claimants

Candidates and claimants to the title of The Man came from ‘everywhere’. The Gundagai Independent in 1898 reported that Mr Laurence Harnett, Sergeant-at-Arms of the New South Wales Parliament was The Man.

“It is not generally known that the hero of Patterson’s (sic) ‘Man from Snowy River’ is none other than ‘Lawrie’ Harnett, the fleshy Sergeant-at-Arms in our Assembly. In his young days Mr Harnett was one of the most fearless horsemen in the colony and can now recount many interesting wild rides over unbroken country.” (Gundagai Independent etc, 7 Sept 1898, p2)

Before that report appeared, Mr Harnett was among a party of gentlemen[xvii] guided by the trusted Mr Spencer to the snow-capped Summit of Mt Kosciusko on another Christmas excursion in 1897. After the ‘Red Ensign’ was hoisted to be the highest flag in Australia and the Queen was given three hearty cheers, Mr Harnett recited The Man from Snowy River. Bernard Ingleby writing for the Evening News said:

“This poem had, besides its intrinsic merit, a double interest – firstly, on account of the ride described having taken place in the Monaro district, and secondly, the Man from Snowy River is actually Mr Harnett himself, so to mention that his rendering was realistic would be superfluous.” (Evening News, 5 Jan 1898, p3)

Refshauge identifies other horsemen including; Jindabyne’s ‘Hellfire’ Jack Clarke; Dargo’s Owen Cummins[xviii]; Tumut’s Jim Troy; Cooma district’s Lachlan Cochrane[xix], the Monaro’s Jim Spencer[xx]; Snowy River district’s George Hedger and Binalong’s A.B. ‘Banjo’ Paterson. These contenders are considered by Refshauge and dismissed with evidence provided. But there is one other horseman that Refshauge writes about and you can’t help thinking that perhaps he is most likely The Man. His name is Charlie McKeahnie from Adaminaby. More about Charlie later.

A Bit About ‘Banjo’

A question sometimes asked; Is ‘Banjo’ himself The Man? Refshauge posed the question but dismissed it. Paterson most likely took part in, or at least observed, wild horse chases in his home area near Binalong, NSW, which captured his imagination. In fact, he said the poem was written to describe the clean-up of feral horses in his own district. He may have aspired to be his own hero, but his horseman character had to be better tested than himself.

In fact, his horseman had to be the best horseman imaginable, riding in the roughest and toughest country imaginable just like the Snowy high country with its rugged peaks and troughs, granite boulders, rock crevices, fallen timber, fens, bogs and swamps. What better landscape than this to set his story and the horseman who could best ride in this landscape would be the best horseman imaginable. Paterson knew how harsh the environment was in Snowy country as he had travelled through on horseback on more than one occasion and met mountain folk and heard momentous stories about horse riding feats.

Paterson in ‘Looking Backward’ (1938),[xxi] written by him to try and quell speculation said as much:

“‘The Man from Snowy River’ was written to describe the cleaning up of the wild horses in our own district, which was rough enough for most people, but not nearly as rough as they had it on the Snowy. To make any sort of job of it I had to create a character, to imagine a man who would ride better than anybody else, and where would he come from except from the Snowy? And what sort of horse would he ride except a half-thoroughbred mountain pony? Kipling felt in his bones that there must have been a well in his mediaeval fortress, and I felt equally convinced that there must have been a man from the Snowy River. I was right. They have turned up from all the mountain districts – men who did exactly the same ride and could give you chapter and verse for every hill they descended and every creek they crossed. It was no small satisfaction to find that there really had been a Man from Snowy River – more than one of them.” (Song, p758-759)

When it came to horses, there wasn’t much that Paterson didn’t know. He understood them, loved them and was a competent and noted rider, also a champion polo player. Rudyard Kipling wrote that he met Paterson in South Africa during the Boer War and with regard to his horsemanship, he said Paterson “rode like an angel.”[xxii] (SMH, 20 June 1900) In the First World War Paterson commanded a Remount Unit squadron in Egypt. When the war ended many of the horses were destroyed leaving Paterson so distressed that he required sick leave to recover.

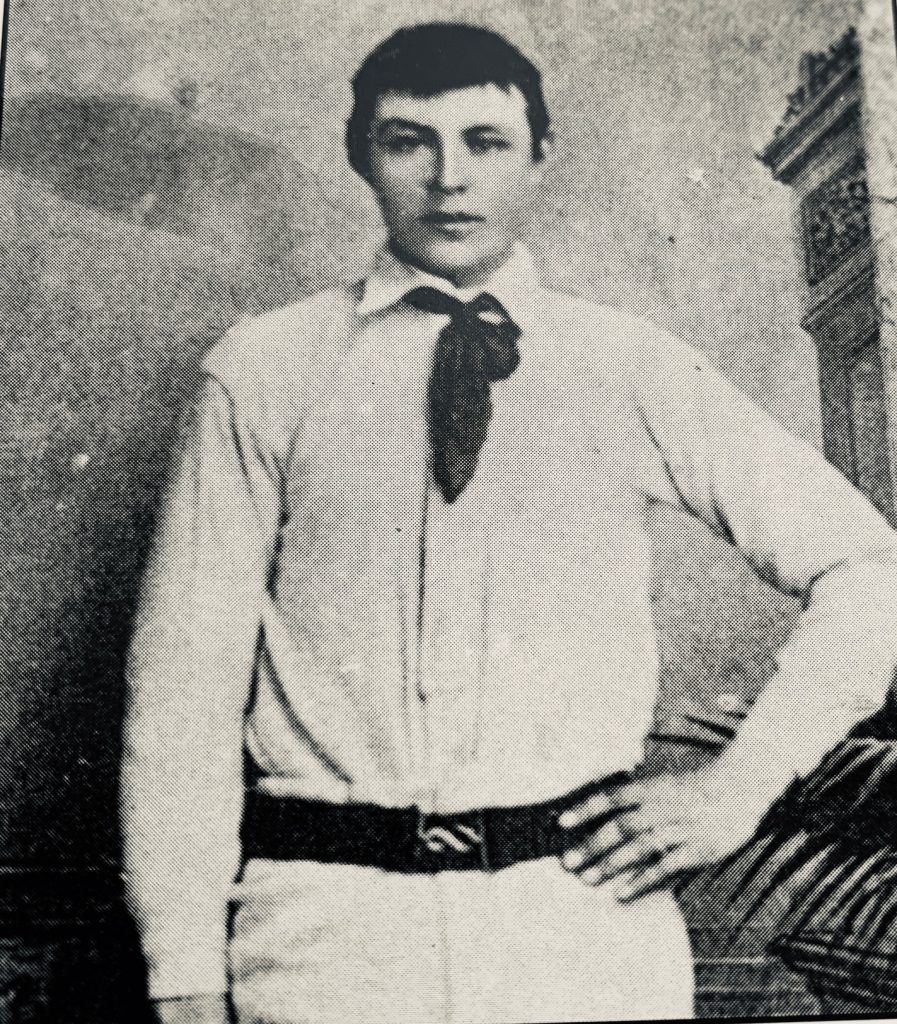

Adaminaby’s Charlie McKeahnie

Charlie was definitely a “stripling” – defined in the Oxford dictionary as a “youth approaching manhood” – which instantly qualifies him as a serious contender. However, given the definition that a “stripling” isn’t yet a man how can a stripling be The Man from Snowy River? A tricky contradiction in terms, but maybe poetic licence.

A sign at the Old Adaminaby Cemetery says that:

“Many men who were familiar with the high country and snow lease areas built trap yards and drove brumbies into them to control the wild horse population and supplement their income. Brumby running parties were organised by groups of stockmen and the group located around Yaouk which included Charlie McKeahnie of Rosedale, hearsay has it that they referred to themselves as ‘The Men from Snowy River.”[xxiii]

But Charlie Mac stood out. If he wasn’t the original hero of Paterson’s poem, he was certainly the hero of Barcroft Boake’s Ballad ‘On The Range’ written in 1891 and published in the Bulletin a year after Paterson’s ‘The Man from Snowy River’. Comparing the two poems I am in no doubt that Banjo’s is the best. However, I am no poetry expert.

Charlie, a fearless rider, was only 17 years when he chased a wild stallion into the rugged mountains north-west of Bolaro around 1885 which became the subject of Boake’s poem. Like Paterson, Boake stayed with the McKeahnie’s when he visited the Monaro, probably to spend time with Charlie’s sister rather than go on brumby hunts with young Charlie.

Paterson heard about Charlie’s infamous ride from Mrs Jim Hassall when they were both visiting mutual friends and Paterson was said to have written down details of the ride. Years later writing to an Adaminaby friend, Harold Locker, Charlie’s sister, Lem (Emily) said in a postscript:

“Forgot to tell you Charlie was the original of the Man from Snowy River. Mrs Jim Hassall was staying with friends and they told the author of the poem (Paterson) the story of Charlie’s ride and he wrote it (the details) there in her presence.”[xxiv]

Maybe Charlie’s ride when he was a stripling did originally inspire Paterson. The ride was certainly extraordinary, thrilling and momentous. He was a hero of the Monaro and his horsemanship was held in the highest regard.

The saddest part of this story is that 10 years after that dashing, dangerous ride Charlie died as a result of a head injury after falling from his horse while cantering across the Bredbo bridge on a wintry August night. He was only 27. His horse stumbled and slipped on an icy patch. Unfortunately Charlie was unable to keep the horse upright and came off hitting his head on the wooden bridge. The accident sounds so innocuous. You could more easily understand if Charlie was fatally injured in a risky brumby chase – but cantering over a bridge? It’s impossible to fathom. Such a cruel irony.

After his death there was a tribute to the fearless rider in a Monaro newspaper which said:

“‘Charlie Mac’ was a great horseman. Australia has produced many fine horsemen and he is entitled to take rank among the greatest of them. He was famous throughout the Monaro country in his day as the champion horseman of a region which bred many of his type – fearless, resourceful, and dashing, capable of riding anything, anywhere, and under any conditions.”[xxv]

Charlie’s Grave

Charlie lies in rest at the Old Adaminaby Cemetery facing the rising sun with Lake Eucumbene and the Snowy Mountains as a backdrop . He has a modest grave with the words:

“In

Loving Remembrance

of

CHARLIE L. McKEAHNIE

Born 29th April 1868

Died 3rd Aug. 1895

AGED 27 YEARS 4 MONTHS

REST”

Another tragedy that preceded Charlie’s death was the death of Barcroft Boake at his own hand. Apparently at the time he was suffering from a broken heart. He was only 26.

Was Charlie The Man?

So was ‘Charlie Mac’ the Man from Snowy River? I think Paterson had him foremost in his mind when he wrote the poem and the poem immortalises not only Charlie but the brave, fearless and thrilling horsemen who were the Men from Snowy River. If I was having money on it however, I’d say Charlie stands out as the real ‘Man from Snowy River’.

‘Banjo’s’ Final Words

When ‘Banjo’ says in the final words of his poem:

“The man from Snowy River is a household word today, …”

He is correct. The Man from Snowy River is still a household word today as is his creator

Wild Horses Today

There are still wild horses in the Snowy Mountains – thousands of them. A recent survey has the number at around 20,000 in the Kosciusko National Park. Across the entire Australian Alps the number is a staggering 25,000 plus. One could say that the horses are now in plague proportions. They are no longer a pest to property owners but a disaster for the natural environment. The crisis has deepened over the past five years with the numbers tripling.

The growing horse population means that our native animals are no longer safe in the Kosciusko National Park. One of the reasons the Park was established in October 1967 was to protect the habitats of these native animals and keep our water sources clean.

Today we are seeing the “hard hooves of over 25,000 feral or wild horses destroying the headwaters of the iconic Snowy, Murray and Murrumbidgee rivers.”* Each horse weighs approximately 400kgs. Times that by 25,000 and you don’t have to be a mathematician or physicist to realise that the delicate alpine grasses, meadows, bogs, fens and waterways don’t have a chance. Let alone the last remaining habitat of the endangered frogs and mammals like the Broad Toothed Rat who survive in the under story of the grasslands.

The brumbies leave little feed for the kangaroos, wallabies and wombats (there is truth in the old saying “to eat like a horse” – they do have big appetites) and the numbers of native animals are diminishing as fast as the horses are breeding and eating.

(* Words of ANU Professor Jamie Pittock. The survey data on the number of feral horses in the Kosciusko National Park was released on 16 December, 2019)

Compare the Boake and ‘Banjo’ Poems

ON THE RANGE by Barcroft Boake (1866-92)

On Nungar the mists of the morning hung low,

The beetle-browed hills brooded silent and black,

Not yet warmed to life by the sun’s loving glow,

As through the tall tussocks rode young Charlie Mac.

What cared he for mists at the dawning of day,

What cared he that over the valley stern ‘Jack’,

The monarch of frost, held his pitiless sway? –

A bold mountaineer, born and bred, was young Mac.

A galloping son of a galloping sire –

Stiffest fence, roughest ground, never took him aback;

With his father’s cool judgement, his dash and his fire,

The pick of Monaro, rode young Charlie Mac.

And the pick of the stable the mare he bestrode –

Arab-grey, built to stay, lithe of limb, deep of chest,

She seemed to be happy to bear such a load

As she tossed the soft forelock that curled on her crest.

They crossed Nungar Creek, where its span is but short

At its head, where together spring two mountain rills,

When a mob of wild horses sprang up with a snort –

‘By thunder!’ quoth Mac, ‘there’s the Lord of the Hills.’

Decoyed from her paddock, a Murray-bred mare

Had fled to the hills with a warrigal band.

A pretty bay foal had been born to her there,

Whose veins held the very best blood in the ‘land –

‘The Lord of the Hills’, as the bold mountain men,

Whose courage and skill he was wont to defy,

Had named him; they yarded him once, but since then

He’d held to the saying ‘Once bitten twice shy.’

The scrubber, thus suddenly roused from his lair,

Struck straight for the timber with fear in his heart;

As Charlie rose up in his stirrups, the mare

Sprang forward, no need to tell Empress to start.

She laid to the chase just as soon as she felt

Her rider’s skilled touch, light, yet firm, on the rein.

Stride for stride, lengthened wide, for the green timber belt,

The fastest half-mile ever done on the plain.

They reached the low safly before he could wheel

The warrigal mob; up they dashed with a stir

Of low branches and undergrowth – Charlie could feel

His mare catch her breath on the side of the spur

That steeply slopes up till it meets the bald cone.

‘Twas here on the range that the trouble began,

For a slip on the sidling, a loose rolling stone,

And the chase would be done; but the bay in the van

And the little grey mare were a surefooted pair.

He looked once around as she crept to his heel

And the swish that he gave his long tail in the air

Seemed to say, ‘Here’s a foeman well worthy my steel.’

They raced to within half a mile of the bluff

That drops to the river, the squadron strung out.

“I wonder,” quoth Mac, “has the bay had enough?”

But he was not left very much longer in doubt,

For the Lord of the Hills struck a spur for the flat

And followed it, leaving his mob, mares and all,

While Empress (brave heart, she could climb like a cat)

Down the stony descent raced with never a fall.

Once down on the level ’twas galloping-ground,

For a while Charlie thought he might yard the big bay

At his uncle’s out-station, but no! He wheeled round

And down the sharp dip to the Gulf made his way.

Betwixt those twin portals, that, towering high

And backwardly sloping in watchfulness, lift

Their smooth grassy summits towards the far sky,

The course of the clear Murrumbidgee runs swift;

No time then to seek where the crossing might be,

It was in at one side and out where you could,

But fear never dwelt in the hearts of those three

Who emerged from the shade of the low muzzle-wood.

Once more did the Lord of the Hills strike a line

Up the side of the range, and once more he looked back,

So close were they now he could see the sun shine

In the bold grey eyes flashing of young Charlie Mac.

He saw little Empress, stretched out like a hound

On the trail of its quarry, the pick of the pack,

With ne’er-tiring stride, and his heart gave a bound

As he saw the lithe stockwhip of young Charlie Mac

Showing snaky and black on the neck of the mare

In three hanging coils with a turn round the wrist.

And he heartily wished himself back in his lair

‘Mid the tall tussocks beaded with chill morning mist.

Then he fancied the straight mountain-ashes, the gums

And the wattles all mocked him and whispered, “You lack

The speed to avert cruel capture, that comes

To the warrigal fancied by young Charlie Mac,

For he’ll yard you, and rope you, and then you’ll be stuck

In the crush, while his saddle is girthed to your back.

Then out in the open, and there you may buck

Till you break your bold heart, but you’ll never throw Mac!”

The Lord of the Hills at the thought felt the sweat

Break over the smooth summer gloss of his hide.

He spurted his utmost to leave her, but yet

The Empress crept up to him, stride upon stride.

No need to say Charlie was riding her now,

Yet still for all that he had something in hand,

With here a sharp stoop to avoid a low bough,

Or a quick rise and fall as a tree-trunk they spanned.

In his terror the brumby struck down the rough falls

T’wards Yiack, with fierce disregard for his neck –

‘Tis useless, he finds, for the mare overhauls

Him slowly, no timber could keep her in check.

There’s a narrow-beat pathway that winds to and fro

Down the deeps of the gully, half hid from the day,

There’s a turn in the track, where the hop-bushes grow

And hide the grey granite that crosses the way

While sharp swerves the path round the boulder’s broad base –

And now the last scene in the drama is played:

As the Lord of the Hills, with the mare in full chase,

Swept towards it, but, ere his long stride could be stayed,

With a gathered momentum that gave not a chance

Of escape, and a shuddering, sickening shock,

He struck on the granite that barred his advance

And sobbed out his life at the foot of the rock.

Then Charlie pulled off with a twitch on the rein,

And an answering spring from his surefooted mount,

One might say, unscathed, though a crimsoning stain

Marked the graze of the granite, but that would ne’er count

With Charlie, who speedily sprang to the earth

To ease the mare’s burden, his deft-fingered hand

Unslackened her surcingle, loosened tight girth,

And cleansed with a tussock the spur’s ruddy brand.

There he lay by the rock – drooping head, glazing eye,

Strong limbs stilled for ever; no more would he fear

The tread of a horseman; no more would he fly

Through the hills with his harem in rapid career,

The pick of the Mountain Mob, bays, greys, or roans.

He proved by his death that the place ’tis that kills,

And a sun-shrunken hide o’er a few whitened bones

Marks the last resting-place of the Lord of the Hills.

The Bulletin, 30 May 1891 [xxvii]

THE MAN FROM SNOWY RIVER by A.B. “Banjo” Paterson (1864-1941)

There was movement at the station, for the word had passed around

That the colt from old Regret had got away,

And had joined the wild bush horses – he was worth a thousand pound,

So all the cracks had gathered to the fray.

All the tried and noted riders from the stations near and far

Had mustered at the homestead overnight,

For the bushmen love hard riding where the wild bush horses are,

And the stockhorse snuffs the battle with delight.

There was Harrison, who made his pile when Pardon won the cup,

The old man with his hair as white as snow;

But few could ride beside him when his blood was fairly up –

He would go wherever horse and man could go.

And Clancy of the Overflow came down to lend a hand,

No better horseman ever held the reins;

For never horse could throw him while the saddle girths would stand,

He learnt to ride while droving on the plains.

And one was there, a stripling on a small and weedy beast,

He was something like a racehorse undersized,

With a touch of Timor pony – three parts thoroughbred at least –

And such as are by mountain horsemen prized.

He was hard and tough and wiry – just the sort that won’t say die –

There was courage in his quick impatient tread;

And he bore the badge of gameness in his bright and fiery eye,

And the proud and lofty carriage of his head.

But still so slight and weedy, one would doubt his power to stay,

And the old man said, “That horse will never do

For a long a tiring gallop – lad, you’d better stop away,

Those hills are far too rough for such as you.”

So he waited sad and wistful – only Clancy stood his friend –

“I think we ought to let him come,” he said;

“I warrant he’ll be with us when he’s wanted at the end,

For both his horse and he are mountain bred.

“He hails from Snowy River, up by Kosciusko’s side,

Where the hills are twice as steep and twice as rough,

Where a horse’s hoofs strike firelight from the flint stones every stride,

The man that holds his own is good enough.

And the Snowy River riders on the mountains make their home,

Where the river runs those giant hills between;

I have seen full many horsemen since I first commenced to roam,

But nowhere yet such horsemen have I seen.”

So he went – they found the horses by the big mimosa clump –

They raced away towards the mountain’s brow,

And the old man gave his orders, “Boys, go at them from the jump,

No use to try for fancy riding now.

And, Clancy, you must wheel them, try and wheel them to the right.

Ride boldly, lad, and never fear the spills,

For never yet was rider that could keep the mob in sight,

If once they gain the shelter of those hills.”

So Clancy rode to wheel them – he was racing on the wing

Where the best and boldest riders take their place,

And he raced his stockhorse past them, and he made the ranges ring

With the stockwhip, as he met them face to face.

Then they halted for a moment, while he swung the dreaded lash,

But they saw their well-loved mountain full in view,

And they charged beneath the stockwhip with a sharp and sudden dash,

And off into the mountain scrub they flew.

Then fast the horsemen followed, where the gorges deep and black

Resounded to the thunder of their tread,

And the stockwhips woke the echoes, and they fiercely answered back

From cliffs and crags that beetled overhead.

And upward, ever upward, the wild horses held their way,

Where mountain ash and kurrajong grew wide;

And the old man muttered fiercely, “We may bid the mob good day,

No man can hold them down the other side.”

When they reached the mountain’s summit, even Clancy took a pull,

It well might make the boldest hold their breath,

The wild hop scrub grew thickly, and the hidden ground was full

Of wombat holes, and any slip was death.

But the man from Snowy River let the pony have his head,

And he swung his stockwhip round and gave a cheer,

And he raced him down the mountain like a torrent down its bed,

While the others stood and watched in very fear.

He sent the flint stones flying, but the pony kept his feet,

He cleared the fallen timber in his stride,

And the man from Snowy River never shifted in his seat –

It was grand to see that mountain horseman ride.

Through the stringybarks and saplings, on the rough and broken ground,

Down the hillside at a racing pace he went;

And he never drew the bridle till he landed safe and sound,

At the bottom of that terrible descent.

He was right among the horses as they climbed the further hill,

And the watchers on the mountain standing mute,

Saw him ply the stockwhip fiercely, he was right among them still,

As he raced across the clearing in pursuit.

Then they lost him for a moment, where two mountain gullies met

In the ranges, but a final glimpse reveals

On a dim and distant hillside the wild horses racing yet,

With the man from Snowy River at their heels.

And he ran them single-handed till their sides were white with foam.

He followed like a bloodhound on their track,

Till they halted cowed and beaten, then he turned their heads for home,

And alone and unassisted brought them back.

But his hardy mountain pony he could scarcely raise a trot,

He was blood from hip to shoulder from the spur;

But his pluck was still undaunted, and his courage fiery hot,

For never yet was mountain horse a cur.

And down by Kosciusko, where the pine-clad ridges raise

Their torn and rugged battlements on high,

Where the air is clear as crystal, and the white stars fairly blaze

At midnight in the cold and frosty sky,

And where around The Overflow the reed beds sweep and sway

To the breezes, and the rolling plains are wide,

The man from Snowy River is a household word today,

And the stockmen tell the story of his ride.

The Bulletin, 26 April 1890.[xxvi]

[i] Here on in called ‘The Man’ where appropriate

[ii] In her eighties, Lem McKeahnie in a private letter in 1960 wrote as an afterthought: “Forgot to tell you Charlie was the original of The Man from Snowy River – Mrs Jim Hassall was staying with friends and they told the author of the poem the story of Charlie’s ride and he wrote it there in her presence.” Quoted in Refshauge, W.F., (2012) Searching for the Man from Snowy River, Arcadia, North Melbourne, p 174

[iii] Refshauge, W.F., (2012) Searching for the Man from Snowy River, Arcadia, North Melbourne

[iv] Paterson, A.B., Looking Backward, 1938 included in ‘Song of the Pen A.B. ‘Banjo’ Paterson Complete Works 1901-1941’, Lansdowne, 1983, p 757-759. Originally published in the Sydney Mail, 21 December 1938.

[v] A.B ‘Banjo’ Paterson ‘Wild Horses’ included in ‘Song of the Pen A.B. ‘Banjo’ Paterson Complete Works 1901-1941’, Lansdowne, 1983 p 580-584

[vi] Mr J Morrison from Beechworth did just that at the Yackandandah Presbyterian Church’s Anniversary in November 1897. See write up in the Ovens and Murray Advertiser, Saturday 13 November 1897, p 6

[vii] Sydney Mail and NSW Advertiser, Saturday 30 March 1895, p 647

[viii] T.W Mitchell quoted in Refshauge, W.F., (2012) Searching for the Man from Snowy River, Arcadia, North Melbourne, p 115

[ix] T.W Mitchell writing in the Corryong Courier in 1962 and quoted in Refshauge, W.F., (2012) Searching for the Man from Snowy River, Arcadia, North Melbourne, p 113

[x] From T.W Mitchell’s letter to the Royal Australian Historical Society 1983 and quoted in Refshauge, W.F., (2012) Searching for the Man from Snowy River, Arcadia, North Melbourne, p 113

[xi]Neville Locker quoted in Refshauge, W.F., (2012) Searching for the Man from Snowy River, Arcadia, North Melbourne, p 115

[xii] Refshauge, W.F., (2012) Searching for the Man from Snowy River, Arcadia, North Melbourne p

[xiii] It’s believed Jack Riley was born in 1841

[xiv] Refshauge, W.F., (2012) Searching for the Man from Snowy River, Arcadia, North Melbourne, p 108

[xv] P Daly quoted in Refshauge, W.F., (2012) Searching for the Man from Snowy River, Arcadia, North Melbourne, p.108

[xvi] Historical information board at the Old Adaminaby Cemetery.

[xvii] The other gentlemen included Commander E.G. Rawson, HMS Royalist; Lieutenant Duff HMS Orlando and Mr R.P Garran

[xviii] https://ehive.com/collections/3492/objects/77420/owen-stephen-cummins-b-13th-september-1874-dargo-flat-shire-of-bairnsdale-vic-d-25th-august-1953-wa

[xix] https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/139008492

[xx] Son of the guide, Mr Spencer, named in the article by W.L.E ‘The Tourist’ in 1894 and the favourite amongst Jindabyne folk as The Man.

[xxi] Paterson, A. B., ‘Looking Backward’, 1938 in Song of the Bush,

[xxii] I’m not sure how an angel would ride. Close to perfect I presume. Letter from Rudyard Kipling on Australian Troops to Mr C.M. Muirhead of Adelaide, Sydney Morning Herald, 20 June 1900, p 8

[xxiii] Historical information board at the Old Adaminaby Cemetery.

[xxiv] Copy of original letter in Locker, Neville, (2003) A Hundred Year Old Mystery. Who was The Man from Snowy River? , Locker, Neville

[xxv] Ibid

[xxvi] http://www.middlemiss.org/lit/authors/patersonab/poetry/snowy.html

[xxvii] https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/on-the-range/

I have a book The Man from Snowy river and other verses by A.B Paterson.

The pages are hand made paper and inside it is signed by a lovely signature of

S.P Sweeny dated 31.1.19. I have no idea where it has come from but found it

my mother’s possessions after she died.

I wondered what your reactions might be.

Mary

I think you have a wonderful treasure there Mary. Do you know who S.P. Sweeny is? It was such a popular book in its time and reprinted over and over again by Angus and Robertson. What a beautiful keepsake. Regards

Sue