Henry “Harry” LINDUPP (1827-1905)

Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex to Healesville, Victoria

Introduction

Henry “Harry” LINDUPP (1827-1905) a poor working-class boy from Shoreham-by-Sea joined the Merchant Navy when he was 17 years old, jumped ship in Sydney, Australia in 1852 and joined thousands of others seeking their fortune during the gold rush. He married an Irish orphan Mary Jane WALSH in 1853 and together they carved a life on the Talbot goldfields for fifteen years where they had seven children. They continued their pioneering life in the late 1860s in Healesville, Victoria having another child and through his hard work and charitable nature Harry went on to earn the respect of the Healesville community.

Shoreham-by-Sea

I walked along Ship Street when I visited the seaside town and port of Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex in September 2018. This is the street where Harry lived and grew up. It was charming, quaint and very quiet. I doubt it was so quiet when Harry was growing up as along with the Lindupp family residence there were around 21 other residences -probably full of kids – as well as stables, a cowhouse, salterns, a rope tackle field and a shipyard at the sea end after you crossed High Street. (The Parish Poor Rates Book of 1827)

Harry was born here on 26 September 1827, the second child of William and Barbara (nee HARDS). They were a poor working family with William described in the Census records as a “Common Labourer”, probably picking up whatever work he could whenever he could. Earning wages at the lowest end of the scale, when work was available, meant life for the family would be one of hard work, uncertainty and struggle.

Harry had five brothers, William, John, Thomas, Rueben and Edward. These boys would be a noisy bunch playing in the street without the added noise of the neighbouring kids, horses and carts rattling up and down, cows mooing and workmen going about their business.

I probably walked past the old Lindupp home and stepped in a few ghostly footprints as I wandered the street. I don’t know the number of the house they lived in.

The Shoreham-by-Sea history portal has a story about Harry’s brother Rueben, who at the age of 65 and then living

in West Street secured himself permanent employment as a ‘turncock’ with the local waterworks company. He was described as one of the old characters of the area and was probably heard before he was seen with his water cart clattering up and down the streets. After Rueben died in 1912 at 77 years the Lindupp name apparently disappeared from the town of Shoreham-by-Sea.

Harry disappeared from the town in 1844 to join the Merchant Navy when he was 17 years old. He worked on numerous ships until 1850 and for a time lived at London’s Sailor’s House a place where unemployed sailors could stay until they secured another seaman’s job.[i]

His seafaring career ended abruptly when he arrived in Australia as a crewman onboard the brand-new Saladin in August 1852. He disappeared, jumping ship a month after arriving in Sydney and finding himself on the NSW Inspector-General of Police’s ‘Wanted’ list with a reward of £3 for his return.

This is Harry Lindupp’s story. A pioneer of the Colony of Australia. My GG Grandfather. I thought I’d start at the end.

Harry’s Death – Healesville, Victoria

Harry died when he was 77 years old, the same age as his brother Rueben. There was an obituary to him in the Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian on Saturday 22 April 1905.

“OBITUARY

It is with the sincerest regret that we have to record the deaths since our last issue of two of the oldest residents of the Healesville district, Mr Henry Lindupp and Mrs McGretton.

The former, who attained the age of 77 years and some months, died early on Friday morning from senile decay, at the residence of his son, Mr John Lindupp, in Blannin-street. He had been suffering from the maladies attendant upon old age for a considerable time and was confined to bed for ten weeks prior to his demise, during which time Dr Baird was attending him. The remains were interred in the Healesville cemetery on Sunday when the Rev. A.C.F Gates conducted the burial service. The funeral cortege was a large one.

The late Henry Lindupp was a colonist of 51 years, and lived in Healesville for 37 years, during nearly all of which time he lived on the Fernshaw-road. He was a prominent contractor, and prior to the advent of the shire council, carried out some important Government road works in and around this district. He leaves the following family to mourn his loss, his wife (Mary) having predeceased him 17 years: W Edward, Henry, George, John, Mrs Holland (Elizabeth), Mrs Norris (Katie), and Mrs T. J. Phillips (Barbara).”

We can surmise from his obituary, that Harry Lindupp through work as a government public works contractor probably acquired modest wealth during his working life. Importantly we can also surmise that he was a highly respected member of the community evidenced by the large turn-out for his final journey. His daughter Mary (Mrs Richard PHILIPPE) who was not mentioned in his obituary also sadly predeceased him, dying from exhaustion four days after giving birth in 1888.

Winding back to England

Call of the Sea

Living close to a port and seeing ships come and go it’s understandable that Harry chose a working life associated with the sea. He was 17 years when he joined the Merchant Navy and according to his ‘Register Tickets’ from 1848-1852, he was 5ft 4 ½- 5ins tall with light hair, blue eyes and a fresh complexion. We later learned that he was able-bodied. He could also write. The picture perhaps of a handsome, fit and intelligent young man who wasn’t tall.

The London Sailors’ House

When he wasn’t on a ship he stayed at London’s Sailors House the brainchild of a Naval Captain by the name of ELLIOT who:

“seeing the miserable lot of Jack ashore set about providing a home for the sailor, where, to some extent, he might be protected from the crimps and boarding-house-keepers who plundered him of his hard-earned wages.” (Launceston Examiner, 12 July 1888)

‘Fool’ or ‘Milksop’?

At the time Harry stayed there it wasn’t very popular with sailors because they felt the House rules were too stringent, much like shipboard. The men who stayed in the house were regarded by many sailors as belonging to two classes – ‘fools’ and ‘milksops’. The ‘fools’ were the ones who got drunk as soon as their feet hit the shore and the ‘milksops’ were the ones, “who were afraid to get drunk in a rational manner or to squander their money on Black-eyed Sue.” And, I don’t think the ‘Black-eyed Sue’ mentioned is of the flower variety. (Launceston Examiner, 12 July 1888)

I am not going to say which category I think Harry fell into. It becomes obvious, I think, as his story unfolds.

Destination Australia

The New Saladin

Harry sailed to Australia in 1852 as a crewman aboard the new Saladin (856 tons), on her maiden voyage. It took 99 days for this new ship to reach Sydney on 6 August 1852 from Plymouth, considerably slower than Captain DAY anticipated due to light winds and calms during the first part of the voyage. On arrival in Sydney Harbour, she was described as “noble” and “as fine a craft as (the) eye could dwell upon”. (Shipping Gazette etc., 14 Aug 1852) She arrived the same day as the schooners, Black Dog, Titan, and the Australasian League.

Man Overboard

The voyage was not without tragedy which struck off the Cape de Verds on 9 May 1852, a day with little wind, still seas and full sail. Ordinary seaman John LYNESS fell off the main yard into the water and was never seen again. There was a thorough search of the area in a manned boat but to no avail. (Empire, 7 Aug 1852) Poor John never re-surfaced. A shocking thing to happen on the Saladin’s first voyage and demoralising for the rest of the crew and passengers.

The Respectable Passengers

A great many “respectable passengers” were on board the new ship enjoying the comfort of “magnificent accommodation”. They were the seven MICHIE family members, Charles TIBBETS, James MACKENZIE, Mr and Mrs Thomas TURNER, Mr H CORNELIUS and 52 passengers in steerage. (Maitland Mercury etc., 11 Aug 1852)

Valuable Cargo

The ship also carried some very valuable cargo, “the greatest quantity of sovereigns hitherto imported in one bottom into the port of Sydney, viz., £126,960”. Not to mention the 5,000 gallons of brandy and 10,000 gallons of rum. (Empire, 7 Aug 1852)

A Leap of Faith

Being a new ship, the crew probably enjoyed better accommodation than they were familiar with on older ships, but it wasn’t enough to keep Harry on board. One month after the Saladin arrived in Sydney, Harry jumped ship. His desertion was reported in the NSW Government Gazette by W.C. MAYNE, Inspector General of Police on 7 September 1852 and a £3 reward was offered for his return. He was described as “A.B.” or ‘Able-bodied’.[ii]

Gold was The Word

Whether planned or coincidental Harry’s timing, securing a job on a ship bound for Australia, was impeccable. The word on everyone’s lips in Australia at the time was “GOLD” and talk on the Saladin was probably about that very subject too.

Most seamen have a taste for adventure and Harry was one of them. He seized the opportunity while he could and ‘jumped’. He was not the only seaman to desert his ship during the gold rush, he and thousands of other seamen and workers deserted city and country jobs to chase their golden dream. Unfortunately for many of these fortune hunters, their future was not paved with gold. The Saladin lost a total of thirteen seamen to the gold rush[iii] in the days between 25 August and 9 September 1852.[iv]

The Ship Jumpers

The reported absconders from the Saladin were: Robert HARVEY, William READ, John NOMMES, Joseph GREEN, John WILLIAMS, Thomas MOREILEN, Henry LINDUPP, Francis WEDDO, Augustus LITTON, John NICHOLE, John LEISHLATER, Edward SMALLEY and Stephen DURANT.[v]

Missing became The Word

“Missing” was a word that must have been on Captain DAY’S lips on this voyage. First to go missing was poor crewman John LYNESS overboard, then a mailbag with 149 letters went missing resulting in charges being laid against him for breach of the Colonial Postage Act, a costly fine and other legal costs, despite the bag being found and handed in (Shipping Gazette etc, 31 Aug 1852) and lastly thirteen of his crew went missing after jumping ship.[vi] He was probably glad to sail off to Calcutta on 6 October 1852, “in ballast” (SMH, 7 Oct 1852) and thankful that the Saladin he captained didn’t meet its end “in an act of mutiny and piracy which began with the murder of its captain and officers” like the previous Saladin ship in May 1844. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saladin_(barque)

Harry on the Run

We know Harry went on the run to Victoria – probably to check out the goldfields and lie low from authorities – because the next record of him is in the ‘Victorian Outward Passengers Lists 1852-1915’, as a passenger aboard the Prince of Wales, which departed Victoria in March 1853 destined for Sydney. The record after this is his marriage in Sydney on 10 October 1853.

Harry Meets Mary

As well as gold fever Harry seemed to have a dose of lovesickness. When and how he met Mary Jane WALSH we do not know, but she was the girl of his dreams and it was a whirlwind romance whichever way you look. Maybe he met her while on shore leave before he jumped ship and promised to come back for her after a time in Victoria. After all, he returned to Sydney some seven months later. Even if he met Mary when he returned to Sydney it was only a few months and they were married. At first glance, they seem an unlikely couple.

Mary arrived in Sydney, Australia with her sister, Elizabeth (Eliza) aboard the Tippoo Saib on 29 July 1850. The girls were Irish Famine ‘Orphans’ from the Mullingar Workhouse in County Westmeath. They came from a town called Castlelost where they’d lived with their parents and siblings until their mother, Elizabeth (Betty), presumably died[vii] leaving father, Peter, to care for the children during the great famine. In Ireland, children were classed as orphans even if they had a surviving parent. Mary was 16 years and Eliza 15 years when they arrived in Sydney. Both were listed as ‘Nursemaids’ and of the ‘Church of Rome’ faith. https://irishfaminememorial.org/orphans/

A Marriage Made in Sydney

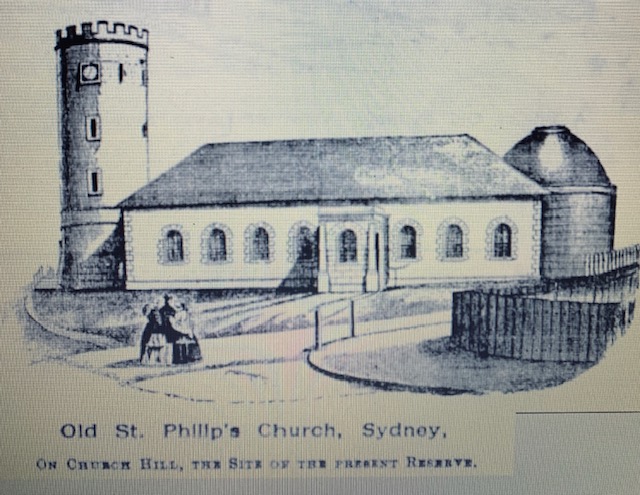

After the devasting events in Ireland Mary may have felt forsaken by the Catholic faith and agreed to marry Harry in St Philip’s Anglican Church, Sydney. Then again, she probably didn’t care. She had fallen in love with Harry, the man she wanted to live with for the rest of her life and share his golden dream. They were married by Banns with the Government’s consent, the ceremony being witnessed by her sister, Elizabeth and one James SCOTT on 10 October 1853. A mixed marriage if ever there was one. A Protestant and a Catholic, an Englishman and an Irishwoman. What would their parents have said?

Harry and Mary’s marriage certificate is the last we hear of Mary’s sister Elizabeth or Eliza Walsh. It’s a family history mystery waiting to be solved. https://www.historysnoop.com/eliza-walsh/

Harry and Mary were married in the second built St Phillips Anglican Church named after the first Colonial Governor, Captain Arthur Phillip RN. (Australian Town and Country Journal, 28 Jan 1888) The first church was built by convicts in 1793 and burnt down by convicts in 1798. The second church operated from 1810 to 1856 and was described as the “ugliest church in Christendom”. The current church is on York Street in Sydney’s city centre. St Phillips is the oldest Anglican parish in Australia.[viii]

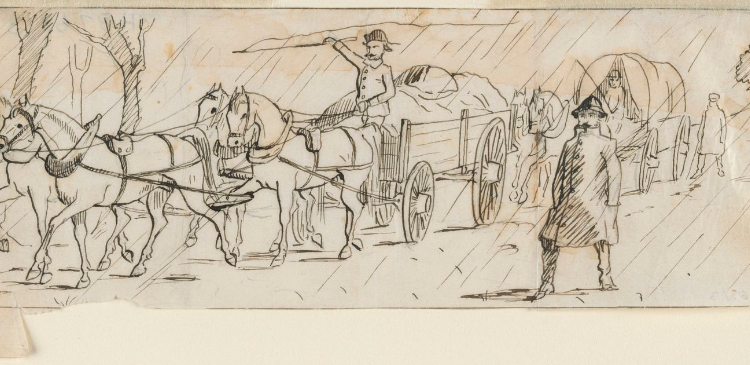

To the Victorian Goldfields

The newlyweds, Harry now 26 years and Mary 19, headed overland to the goldfields of Victoria. There are no records of them sailing in the coastal passenger lists. They faced a long, arduous, uncomfortable and hazardous journey with the limited choices of travel available to them. They could walk (unlikely), go by horseback (unlikely), cart, wagon, dray or coach. Whichever way they travelled it was no honeymoon. It would also cost money.

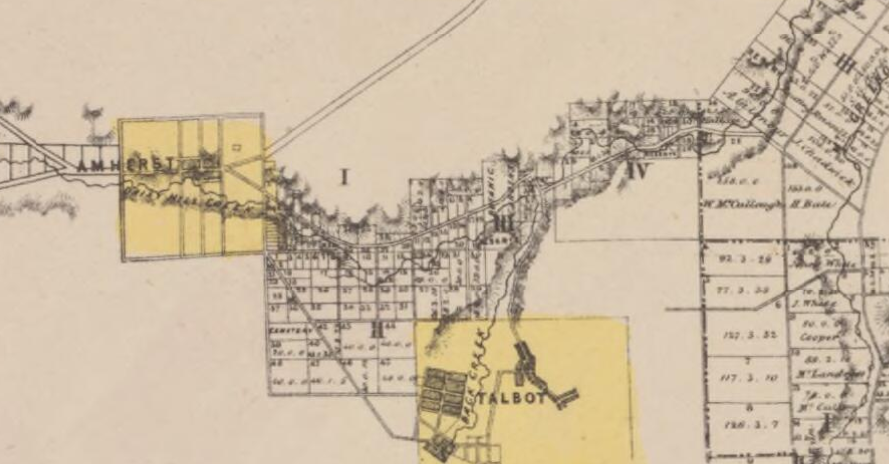

Their final destination was either Sandhurst (later Bendigo) or a newish gold mining area called Nuggetty Gully, in the area of Talbot and Amherst about halfway between Ballarat and Bendigo. Today the 930 km (578 miles) or so car trip takes around 10 hours from Sydney using the most direct route. In 1853 they were travelling on poorly made roads or tracks dodging holes and stumps, in good weather and in bad. Rain meant mud and mud meant getting bogged.

For some perspective, it took around 14 days to get to the Bendigo goldfields from Melbourne by bullock dray, a trip of around 95 miles (153 km). The trip from Sydney is around six times further and equates roughly to 85 days on the road. Phileas Fogg travelled around the world in less.

Planning and Saving for the Journey

I believe Harry put some serious thought into planning their travel to Victoria and their future life on the goldfields. He probably acquired work and saved money before leaving Sydney with Mary by his side. One of the theories suggested by a descendant, GG Granddaughter Carol Yates, is that he may have worked on coastal ships travelling between Sydney and Melbourne. Money could be easily saved in this work as food and board came with the job while at sea. It was the temptations onshore that saw many a seaman skint.

Work onshore was probably easy to find in both city and country areas as there was a huge exodus of working-age men leaving their jobs for the goldfields. Another possibility is that he may have already been to the goldfields in Victoria and sussed the area out before heading back to Sydney with enough earnings to enable him to marry Mary and take her to a new life.

Whichever way acquired, money was needed to buy something on wheels and an animal to pull it, plus camping equipment, food and feed for the horse or bullock. Costs may have been shared with other people or another couple. Travelling with others on such a long journey would make sense for company and safety reasons alone. Opportunistic bushrangers lurked. They probably camped under the stars or under their cart, wagon or dray hearing strange noises coming from the Australian bush by night and seeing strange looking animals and birds by day.

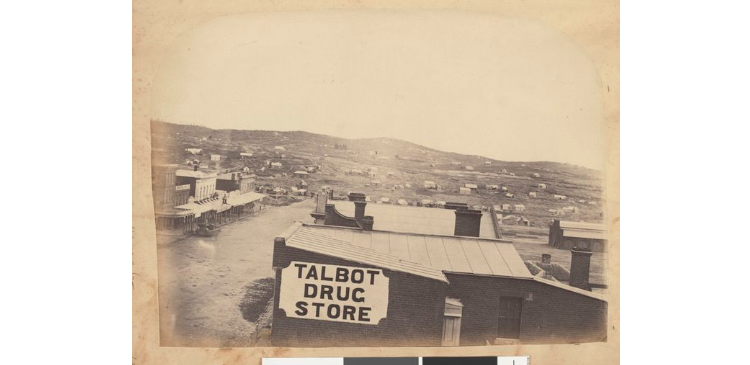

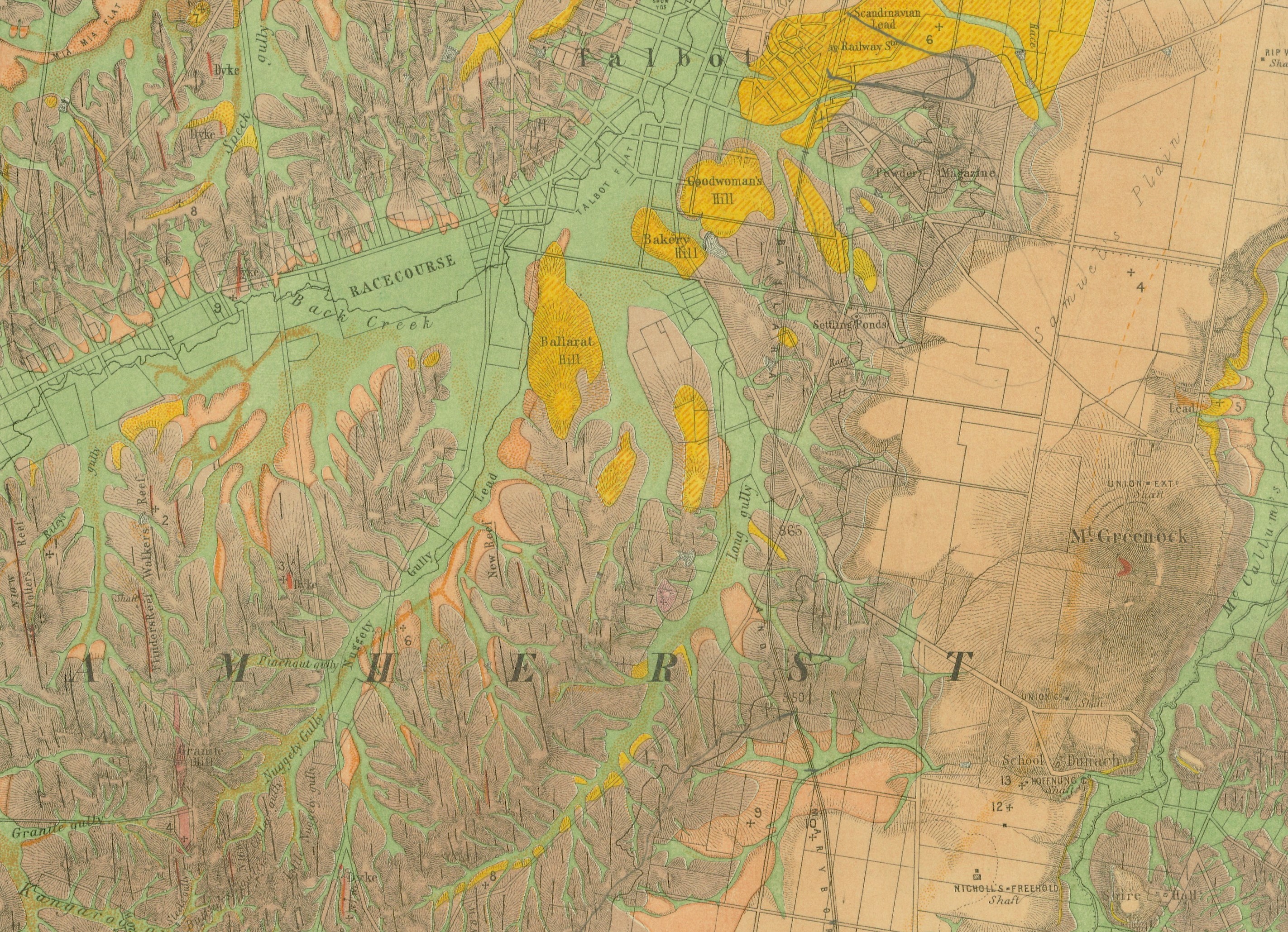

Living on the Goldfields – Nuggetty Gully,[ix]Back Creek, Talbot

Nuggetty Gully later called Talbot was in the area of Daisy Hill later called Amherst. The first unofficial record of a gold discovery was at Daisy Hill on the Hall and McNeill’s “Glen Mona Run” in 1849. Shepherd, Thomas CHAPMAN made the discovery but kept it a secret fearing he’d be prosecuted for gold-digging. The first official discovery was made by two South Australians, CROWLEY and John POTTER at Daisy Hill Creek in 1852 while digging out a bogged wagon.

First Rush

By the end of 1854, there was a big rush to Daisy Hill and Back Creek. This was the area where Harry and Mary made their tent a home along with another 2,500 diggers, including 300 women and children.[x] Stores opened up at Back Creek (also later called Talbot, from 1862[xi]) to cater for the needs of the growing population. In May 1855 the Chinese started arriving and setting up camps in Long Gully and Nuggetty Gully increasing the population further.

Lindupp Babies Start Arriving

1855 was also the year Mary gave birth to their first baby, William Edward. Records say that William, known as Edward, was born in Sandhurst, the old name for Bendigo. This suggests that Harry and Mary may have first lived on the Bendigo goldfields, a distance of some 43 miles (69ks) from Nuggetty Gully.

If they were living in Nuggetty Gully major planning would be needed to get to Sandhurst for the birth given that it would take around six days by wagon to reach Bendigo on the poor roads. Such a trip may have been necessary if there was no doctor or midwife in Nuggetty Gully at the time. This was after all their first baby – a daunting and stressful prospect for young Mary. Then again, Sandhurst may have been where the birth was actually recorded, not where the birth took place.

Baby number two, Henry was born in 1856 at Daisy Hill followed by a third son, George born in 1858 at Amherst, the new name for Daisy Hill.

Nuggets Galore – Another Rush

Nuggetty Gully lived up to its name because it was rich in gold but especially good-sized nuggets of good quality. There were regular newspaper reports of large nuggets being dug up weighing between 100-200ozs (2.8-5.6kgs).

In May 1858, the Mount Alexander Mail reported:

“Our correspondent informs us, that on Tuesday last at Nuggetty Gully a nugget weighing 85ozs (2.4kgs) was found at 2ft sinking. Hundreds of nuggets have recently been found, and the locality is described as yielding a sterling living to all engaged. Moreover, it is said, that there is plenty of unoccupied ground which would pay well, and miners who are not at profitable work should visit the spot.” (Mount Alexander Mail, 14 May 1858)

A month later a lucky Irishman discovered a nugget weighing close to 116ozs (3.3kgs) resembling the shape of a vine leaf and was very pure. (The Age, 24 June 1858)

The population in the area kept rising, especially after two deep leads one from Nuggetty Gully and the other from Ballarat Hill joined up in 1859. These leads were rich in gold and the population exploded. Tents were going up in every available spot and there were estimates of 15,000 people at one point.

Rumours of gold finds would quickly sweep around the town and diggings. A newspaper correspondent reported in October 1859:

“There was a current rumour through the town that a nugget of a most enormous size had been discovered yesterday in the neighbourhood of “Nuggetty Gully”. The weight was stated to be 160 pounds (72.5kgs), but despite all my enquiries at likely quarters, I entirely failed to obtain satisfactory accounts.” (The Star [Ballarat], 31 Oct 1859)

By November 1859, ‘The (Ballarat) Star’ reported that the rush near Nuggetty Gully:

“… is now likely to become a valuable acquisition to our mining resources. There are about 5,000 diggers at work, but none have bottomed except the prospecting claim. Idle diggers we have none. Everyone finds an opening in some hopeful spot or other, and certainly there are no symptoms of any miner’s family being in want of their domestic requirement. We have at the present moment room for double the number of our diggers, but the extra number must be possessed of some little capital, as our sinking is deep and remarkably wet.” (The Star, 7 Nov 1859)

The Star report paints a positive picture of the area and for the Lindupp family. From the report, we can presume that Harry is working hard and providing well for Mary and their children.

The Scandinavians

Prospecting became a form of mania and as soon as prospectors announced a find of quartz, claims were staked. In May 1859 two Scandinavian prospectors Charles OLSON and John LARSON discovered quartz at Little Cockatoo and 40 claims were taken up in the area. The reef was christened the Scandinavian. (Argus, 25 May 1859)

By 1862 there was a street named Scandinavian Crescent and while the reef might have brought riches a devasting fire in December 1862 wiped out many businesses including five hotels along the street. The Argus reported:

“A destructive fire broke out this morning in the Scandinavian-crescent, Talbot. Cause unknown. The following houses destroyed: – Henderson, bootmaker; Bowman, bootmaker; Ford, fruiterer; Frazer, hairdresser; Golden Cross Hotel; Samuel’s, gold assayer; Theatre Royal and Hotel; Wilarke, stationer; Evans, tentmaker; two unoccupied buildings, London Tavern, Scott’s hay and corn store; opposite side street – Municipal Chambers, London and New York Hotel, Rob Roy Hotel, Harris’s school. Total loss, about £12,000. Fire burning for two hours and a half.” (Argus, 5 Dec 1862)

The 1859 rush turned out to be massive. More and more people converged on the area and the population at Back Creek reached 30,000 within a few months. More and more businesses started up to cater for the growing population and Scandinavian Crescent became the High Street of Back Creek and Back Creek became Talbot.[xii]

The list of businesses and the type of businesses destroyed by the 1862 fire is an indication of how the area had grown since the first rush in the mid-1850s around the time Harry and Mary arrived. They would have met many people from diverse backgrounds and witnessed many events and incidents both positive and negative that would make a lasting impression and help shape their future values and beliefs.

Crime but No Cops – A “Reign of Terror”

Crime grew as the population grew but there were not enough policemen to protect the lives and property of the 30,000 people who had assembled into an area of around 3 to 4 square miles, or 4.8 to 6.4 square kilometres. It was high density living in the extreme. There were nine policemen, two mounted men, two sergeants, and five constables – a ratio of 1:3,333, hardly sufficient for proper law enforcement.[xiii] Criminals – murderers and robbers – were set free from the Back Creek lock-up because there was no sentry to guard them. They weren’t even handcuffed.[xiv]

An unnamed correspondent wrote a descriptive piece dated 20 April 1859 for the Argus about the level of crime at Back Creek, which painted a grim and terrifying picture:

“All the usual characteristics of a populous rush are to be observed here: drunkenness and dissipation in all its multitudinous phases are to be encountered at every step; crime stalks abroad; midnight robberies and burglarious entrances form the principal records entered on the sheets of the police court. The storekeepers are being plundered almost with impunity; brass is palmed off for gold; sticking-ups are frequent; broken heads and blackened eyes manifest but too plainly in the morning the doings of the previous night. The police are powerless, and we of the peaceable and industrious classes are literally left to the fury of the waves.

Such in a few words – and the picture is not heightened by coloring (sic) – is a description of these diggings at the present moment. I have visited many rushes in this and the neighbouring colony of New South Wales, but never have I seen one abounding with more of open-day immorality than that of Back Creek. Take Friday and Saturday nights last as an example; as specimens of brutality on the lowest scale – as examples of what men can and will do when they are infuriated by overdraughts of alcohol – as proofs of how the animal propensities predominate, over the human reason, these two nights are without parallel. The evenings of these days opened somewhat calmly. There was no indication of a row. The theatres were well filled. The singing and dancing rooms fully tenanted. The professors of biology and electro-biology were famously patronised. The panoramas had numerous visitants. Music was in the ascendant; and the streets presented a multitudinous array of young and old, grave and gay, of both sexes. But between the hours of 12 and I, when the process of nobblerising had begun to operate – when very many parties were as full as they could hold – when, staggering upon their legs, another glass would have toppled them right over, out they came and for Ballarat street they made. They were ready for a fight, firmly intent upon preparing themselves for the duties of the Sabbath by brandishing sticks, hurling stones and bottles, and making these and every other available missile tell with powerful effect upon the sconces of all who would dare to ‘tread upon their coats.’ About 2 o’clock the battle commenced – and such a battle. They seemed like so many demons let loose from a place unmentionable. Hundreds were engaged in the mélée, and friends and foes were alike assailed. There was very little of deliberate aim taken. A blow anywhere satisfied the fiercest of the belligerents; a clip on the crown of the head of the antagonist, the smash of an arm, the staving in of a rib, or the dislocation of a thigh, was all the same to them, provided they so disabled the combatant as to render him an imbecile or a cripple for life; and this they succeeded in doing in many instances.”[xv]

The unnamed author went on with a description of the morning after – a street bloodied and littered with sticks and broken glass; weary inhabitants of the neighbourhood who didn’t get a wink of sleep because they needed to guard their “frail calico tenements from destruction.”

Questions were asked of why there was no police presence to deter the street fights at midnight and the robberies and burglaries that you could hear happening in the streets; where “the shops and stores of the butchers, bakers, shoemakers, grocers, tobacconists and jewellers” were plundered; where tents were “ripped open” at the top or sides and whatever was in reach taken; and where highway robberies happened all too frequently. Even a case of child sexual abuse was noted by the author.

There was a hint of desperation and helplessness in this article, a feeling that the government had let the area down. Law and order were out of control and something needed to be done to end “the reign of terror.”[xvi] The author called for storekeepers to form night patrols to protect themselves and their neighbours;

“if the Government will not help us, we must help ourselves.”[xvii]

Back Creek Residents vs Amherst Council

Around the same time friction was brewing between Back Creek residents and the Amherst Council. Amherst had been made a municipality with an elected Council before the boom at Back Creek. The problem was, Back Creek’s population had become vastly bigger than Amherst’s, requiring more and more government services. Amherst collected rates from the people at Back Creek but spent most of the ratepayers’ money in Amherst. Back Creek residents were understandably aggrieved and there was a hint of growing rebelliousness within the community. (Wilkie 1947)

While I don’t know where Harry and Mary lived specifically, they probably lived in an area close to other families and away from the town’s excesses. Wherever they lived personal safety and property protection would be uppermost in their minds. Schools and hospitals would also be important to them as a family and eventually, these services came to the area.

By1864 Talbot could boast:

“ … a Court house, borough offices, 7 schools, a street of shops, 2 breweries, churches, 2 soap and candle factories, 16 hotels, coach services and general carriers. It also had a population of 3,400. There were also cultivation blocks and dairy farms and a common pasturage which operated with the aid of the pound keeper.”[xx]

Harry and Mary’s family kept growing while they lived in the gold mining area. Talbot was officially named in 1861, the same year Mary gave birth to their first daughter, my G Grandmother, Elizabeth. Mary was born in 1863, John in 1865 and Kate in 1868. Seven of their children were born on the goldfields. This was the average number of births for women on the goldfields over a fifteen to twenty-year period according to Susan Lawrence.[xxi]

Harry and Mary ended up spending fifteen years at Nuggetty Gully/Back Creek/Talbot which suggests Harry made a steady living from mining and adapted to life on the land rather than the sea. Whether he was a self-employed miner or working with a group of miners or for a gold mining company we do not know for sure.

Susan Lawrence says:

“changes in the mining laws of the 1850s provided for Miner’s Rights and goldfields commons. As well as giving the miners authority to vote and make laws, these provisions entitled bearers to claim land to live on as well as to work and to use the land for subsistence farming and stock raising. It was within the space that those with Miner’s Rights built their homes and planted their gardens.”[xxii]

I can imagine Harry and Mary establishing a garden and growing their own food on a small piece of land on the goldfields. It would certainly stand them in good stead for their later life in Healesville where gardening was more than a hobby.

The quality of life of miners and their families improved throughout the 1860s and ’70s as the transportation network improved and agriculture expanded around Ballarat. More goods could be brought into the area to make work and domestic life easier and more diverse from machinery and construction materials to luxury household groceries like jam and soft drinks.[xxiii]

Alluvial to Deep Shaft Mining

By 1862, Wilkie writes that both Amherst and Talbot had reached their peak as alluvial gold mining towns and the trend moved to deep shaft mining which continued for several decades. This sort of mining required capital which only companies could provide. The days of the individual self-employed miner were numbered and they started to disappear from the scene. (Wilkie, 1947)

Mining Days Come to an End and Healesville Beckons

Harry had decided his mining days were over by the late 1860s but his pioneering spirit was still very much alive. He would have read or heard of new land and opportunities opening up north-east of Melbourne in the Healesville District, and this is where he took his family to continue their pioneering life.

Family Life in Healesville

The Lindupp’s moved to Healesville sometime between 1868 and 1870. We know this because Kate was born in 1868 in Amherst and Barbara was born on 13 October 1870 at Gracedale, Healesville. The journey to Healesville was about 134 miles (216 km). By bullock dray, the trip would take around three weeks.

Healesville was another Victorian town established because of gold, not because it was discovered in Healesville, but because the township was situated near the junction of the Watts River and the Grace Burn and provided better access by road to the Woods Point goldfields.

The township was surveyed in 1864 and the first land sales took place in June 1865, so by the time the Lindupp’s arrived the township was established but the surrounding area was still developing. The Woods Point General Directory of 1866 had around 50 listings.[xxiv]

Fernshaw Road

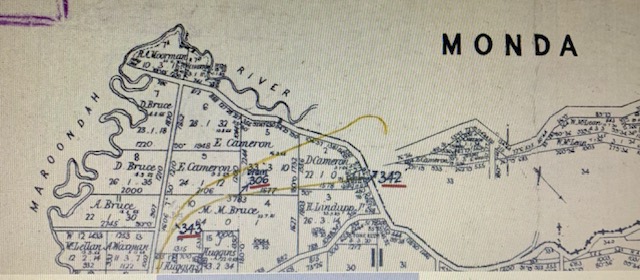

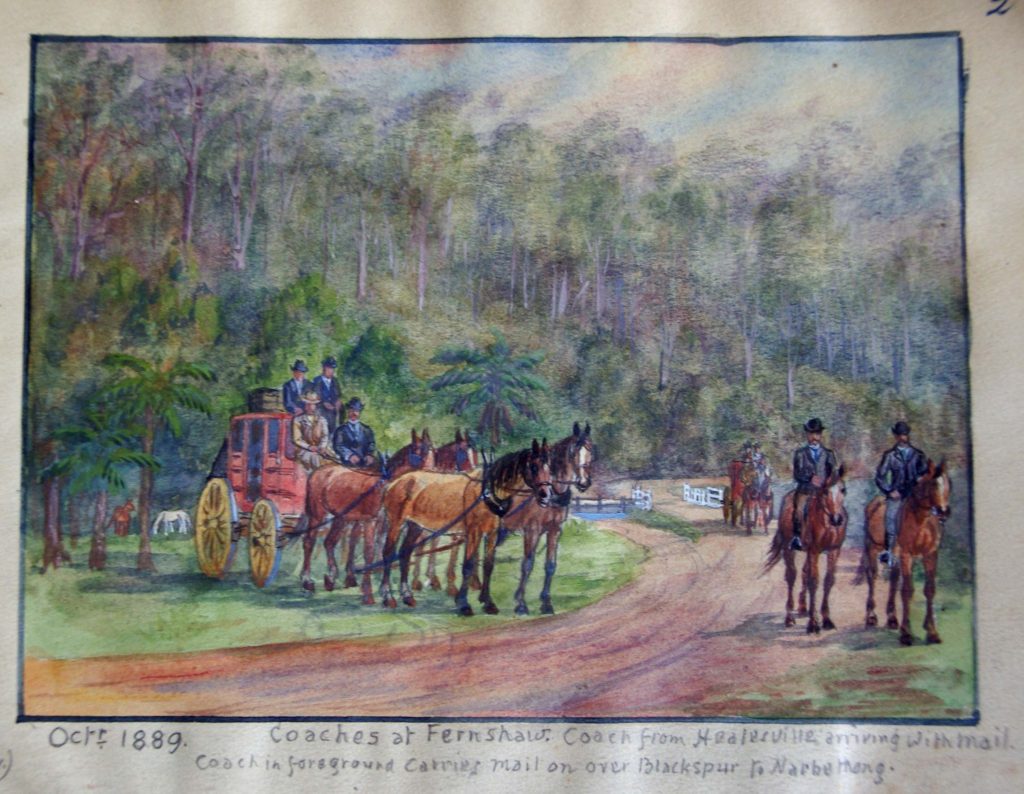

According to my grandfather, his grandparents, Harry and Mary were the first residents of Fernshaw[xxv], a small township 63 km (39 miles) northeast of Melbourne and 10 km (6.2 miles) northeast of Healesville. But, they actually lived on the Fernshaw road three miles out of Healesville in a spot referred to in Electoral rolls as Gracedale. Fernshaw, about three miles from the Lindupp’s gate, was a place renowned for its natural beauty and is described in ‘Victorian Places’.

“Situated on the Watts River, near where a log had fallen making a convenient crossing, Fernshaw was settled in the 1860s. It provided good country for orchards and berry growing.

The location was at the foot of Blacks Spur with Mounts Juliet and Mondah rising on either side, providing spectacular scenery. There were nearby fern gullies giving rise to the name – ‘shaw’ is old English for thicket or wood. By 1875 Fernshaw had a post office (1865), two hotels, a school (1871) and stores. It was famed for its beauty, attracting tourists.

In 1886 the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) began work of the Watts River Catchment Scheme – later to become Maroondah – and the Board obtained approval for the catchment country to be reserved and kept free of settlement. This required the removal of the Fernshaw township which was completed by about 1890. (https://www.victorianplaces.com.au/fernshaw)

In 1903 it was described in the Australian Handbook:

“FERNSHAWE … , on Watts River, in the county and electoral district of Evelyn, 45 miles NE of Melbourne. The Healesville railway station is a distant 7miles. Coaches run to Marysville. The surrounding country is famed for the beauty of its scenery, there being numerous fern-tree gullies, lofty water-falls, and extensive mountain views, and the timber is reported to be among the largest in the world, the mountain ash attaining the height of 420 ft. There is also much valuable wood, such as the myrtle, sassafras, &c. There is no township, the Crown having reserved the land for water supply purposes.” [xxvi]

Orchardists and Contract Labourers

In the Healesville and District Historical Society publication, ‘A Pictorial History of Healesville – From A Village to a Town 1864-1920’, the Lindupp family were described as early settlers in the Healesville area. It says:

“In the 1880s Harry Lindupp and his family had a small orchard and farming property on the Fernshaw Road near Gracedale House. The property produced fruit and flowers of very good quality which were supplied to the coach travellers passing through to Fernshaw and Marysville. ‘Lindupps’ became a regular stop for the coach traffic.”[xxvii]

The property became a landmark of sorts. Mentions of ‘to’ and ‘from’ “Lindupp’s Gate” and “Lindupp’s Hill” appeared often in local newspaper stories.

Henry Lindupp Snr was consistently described as a “Labourer” in the Rate Paying Rolls of 1889/90 (“owner of House, Gracedale”) and 1894 (“Land, Gracedale”) and in the Electoral Rolls of 1889-90, 1894 and 1903. Henry Lindupp Jnr was described as an “orchardist” in Gracedale in the 1906 Electoral Rolls. The description above sounds as if the orchard and farming was a joint family enterprise. Later documents show that Henry Jnr and William Edward both produced fruit.

In William’s case, he cultivated apples, peaches and raspberries on about an acre and a half of land. (The Age, 15 Dec 1993) In Henry Jnr’s case, he cultivated blackberries as well as other fruit and voiced his concern about the Shire Council bringing blackberries under the Thistle Act in January 1900.

He said: “Very often a hedge of blackberries saved an orchard, as the birds would attack the berries and leave the other fruit alone.”

“He did not think that for the sake of those who let the berries grow wild others who cultivated them for use should be made to suffer as would be the case if it came under the Thistle Act” (Healesville Guardian and Yarra Glen Guardian, 12 Jan 1900)

Henry Jnr wouldn’t get much support today, with blackberries such a scourge on the bush environment and a costly weed for farmers, graziers and National Parks people to manage and control.

As growers of fine fresh produce, members of the family were very involved in the establishment of the Healesville Horticultural Society and were prolific and successful exhibitors at the shows. The men did well with their fruit and vegetables and the women did well with their preserves and baking.

Grapes Fit for a King

Even though Henry Jnr was described as a “Carter” in the 1894 Electoral Rolls and a “Labourer, Owner, Land, Gracedale” in the 1889-90 Roll, he grew grapes fit for a King. The Healesville Guardian reported on Friday, 23 March 1894:

“On Monday last we were presented by Mr H Lindupp Jun, of Gracedale, with a really magnificent sample of grapes of the Black Prince variety. The sample was simply excellent, and the fruit most delightful to the taste. The bunches were large and well formed, while the berries were uniform and of great size. We take this opportunity of thanking Mr Lindupp for his kind present, and at the same time assure him that we experienced a treat to be “envied by a King.” The numerous examples of perfection to which the grapes attains in and about Healesville proves without a doubt that this fruit can be successfully cultivated and the wonder is that more attention is not bestowed upon the raising of this fruit for the market, especially the table varieties, which seem to thrive best.” (Healesville Guardian, 23 Mar 1894)

Little did the Healesville Guardian know in 1894 that the Yarra Valley in the next century and the century after would gain national recognition as one of the finest wine growing regions in Australia.

Men of Temperance

Henry Jnr was probably not that inclined to grow grapes of the wine variety as he and his father Henry Snr were both members of the Healesville Tent of the Independent Order of Rechabites (IOR) Lodge 119 – the only fraternal or friendly society based on temperance. Members signed a pledge to abstain from alcohol and by making small regular contributions they could insure themselves against sickness, death and hardship. The IOR became established in Victoria in 1847 and you could say, was the precursor to modern-day health insurance.[xxviii]

The two Henrys obviously took their membership and temperance seriously. In 1902 “Bro. H. Lindupp Snr” was re-elected Treasurer of the Healesville IOR and Henry Jnr was elected the money steward. Henry Snr was also elected a “juvenile superintendent”. (Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian, 20 Dec 1902)

This was a period when there were over 36,000 members of the Victorian Rechabites encompassing around 250 tents (as their meeting halls were called). Today there are only 700 members.[xxix]

An Oddfellow

John Lindupp, son number four, was a member and office-bearer of the other fraternal order in town, the Oddfellows or specifically the Loyal Healesville Lodge M.U.I.O.O.F.[xxx] (Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian, 3 Dec 1904)

Being a member of either Lodge, the Rechabites or the Oddfellows was a way of helping others and being a part of something bigger than yourself. If you drank the Oddfellows was for you. In a similar fashion to the Rechabites, the historic command of the Oddfellow is to “visit the sick, relieve the distressed, bury the dead and educate the orphan.”[xxxi]

A Musical and Sporty Bunch

John was “one of Healesville’s favourite singers” (Lilydale Express, 8 April 1893). He was a baritone and rated mentions regularly in the old local newspapers. He also rated mentions in the local papers as being associated with Healesville’s Turf Club, Cricket Club, Football Club, Rifle Club and Billiard tournaments – a local entertainer and all-round sportsman by the look. Older brother, George, was also a cricketer and shooter.

In a similar style, Katie and Barbara Lindupp were popular singers and entertained the Healesville community with both solo acts and duets at charity, church and social functions. Not only were they musical but ‘sporty’ too. They are mentioned in the local papers playing tennis and competing in shooting tournaments at the Rifle Club. Katie scored quite well in competition shoots and would probably rate as a ‘good shot’.

Tragedy Strikes

Like many families in the 1800s, the Lindupp family was not without tragedy. The family went through a period of deep sorrow that began just before Christmas in 1888 with death after death after death over a period of four weeks.

What should have been a joyous time turned into a nightmare for second daughter Mary who died from “exhaustion” after four days in labour where she gave birth to an unnamed baby boy on 19 December 1888. The tiny new-born lived for two hours, Mary lasted a few more. Nine days later on 28 December, 1888 Mary’s 11-month-old daughter Louisa Mary (Lu Lu) died from Diphtheria after suffering for three days.

Mary’s death was reported in the ‘Local News’ in the Lilydale Express on 22 December 1888:

On Wednesday last a gloom was cast over Healesville, when it became known that the wife of Mr R. Philippi, an old resident of the town, had breathed her last, at her residence on St Leonard’s road. The sad event occurred about 1 pm. The deceased lady had been ailing for a few days with a sore throat, but nothing serious was anticipated. A few hours before her death Mrs Phillipi gave birth to a child, which lived about 2 hours and then expired, the mother dying a few hours after the child. The deceased was only 25 years of age and had been a resident of the district for 20 years, and was the second eldest daughter of Mr H. Lindupp, Sen., of the Fernshaw Road. She leaves one child, about 12 months old. The funeral took place on Thursday afternoon and the deceased being interred in the Healesville cemetery, a large number of people from all parts of the district attending. Mr J. Green J.P., of the Mission Church, officiated at the grave. Universal sympathy has been expressed for the deceased’s husband and relations in their sad bereavement. (Lilydale Express, 22 Dec 1888)

Little did they know that Mary’s 11-month-old daughter Lu Lu would die from Diphtheria nine days after her Mother and newborn brother. Mary’s death certificate says she died from “exhaustion after childbirth” but maybe her “sore throat” was the dreaded Diphtheria as well. The baby’s death was due to “premature birth” according to his death certificate. The future for this baby would have been bleak arriving in a household in the grips of Diphtheria. Thank goodness for our modern vaccinations.

Unbelievably, within five weeks of her daughter dying after a traumatic birth, Mary aged 54 years, wife of Harry Snr for 36 years and mother of their eight children died on 31 January 1889. Mary died from “disease of the heart”, a condition she suffered for four weeks according to her Death certificate.

You can’t help but wonder if Mary died of a ‘broken heart’ witnessing her daughter die in such a distressing and painful way after she herself had given birth to seven babies in the harsh conditions of the goldfields. Understandably her grief would be overwhelming. To watch her beloved daughter take her last breath and then the only living reminders of her, her two babies, dying as well would be too much for any mother and grandmother to bear.

Mary lies in a grave behind her daughter and grandchildren at the Healesville cemetery.

‘Life Goes On’

As the saying goes ‘life goes on’ and in September 1889 we gain further insight into Harry’s life, values and belief system that namesake Henry Jnr. embraces as well. They both attended a public meeting held at the local Healesville Daly’s Hall to express sympathy with the striking London Dock Laborers (sic) and to raise a fund for their assistance. About 30 people turned up to support the strikers’ demand for 1d per hour.

Two resolutions were endorsed:

“That this meeting desires to express its sympathy with the distress amongst the dock laborers (sic) in London, and urges all who care, to promote and encourage the efforts now being made for their relief.”

And:

“That this meeting resolves to contribute towards the funds now being raised for the relief of the London dock laborers (sic).”

The Lilydale Express reported:

“Mr H Lindup, jnr., had much pleasure in seconding this resolution (#2). He was surprised at the small attendance, seeing that it concerned every working man. They should help their London brethren, as the men here might be placed in the same predicament and they would have the compliment returned. He thought that they could not obtain the 1d per hour unless by strike.” (Lilydale Express, 14 Sept 1889)

“Mr H Lindupp, sen., said he had been a great many years in this colony and he had been about the docks a great deal in his younger days. He described the terrible scenes enacted there for the purpose of obtaining work, if only for an hour. In reference to families being in one room he had seen three families in a room 12ft square. The present meeting was a disgrace to Healesville, as he had seen the Hall crowded for a purpose which was frivolous to the present object. (Cheers) He hoped that Healesville would follow the steps of other towns in the colony and show their sympathy in a practical form. He had much pleasure in supporting the resolutions.” (Lilydale Express, 14 Sept 1889)

The meeting ended up raising £3 12s.

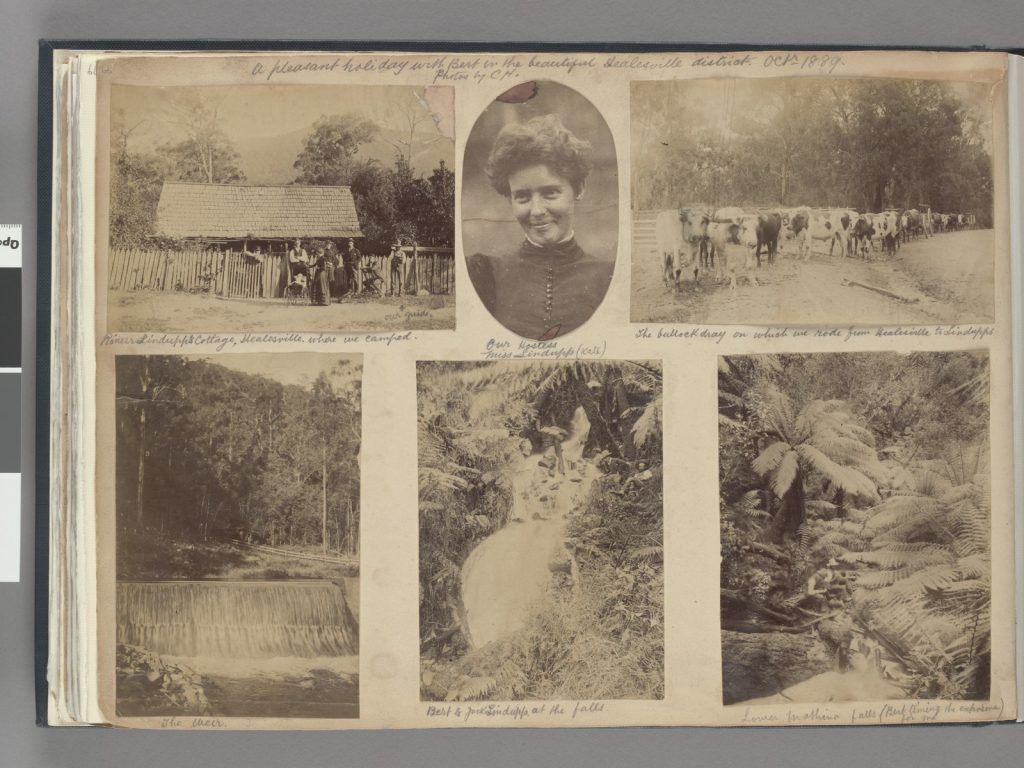

Melbourne Artist Charlie Hammond Camps at The Lindupp’s

In October 1889, Charlie Hammond a talented Melbourne artist and photographer visited Healesville with his brother Bert and camped at the Lindupp property. Some of the photographs of his time exploring the area with Jack Lindupp as a guide and photos of the Lindupp family are on page 91-92 of Sketchbook 2 held at the State Library of Victoria (SLV)

Lives Lived Well

The Lindupp family headed by Harry Snr and Mary was one of the many pioneering families who helped build and define our nation from the grassroots. From poor and humble beginnings they did their best to be good citizens and carve out a future in a new frontier. It is clear that they were well known and well regarded within the Healesville district. Their names appeared regularly in the local papers, from the social and sporting pages to the news pages.

They weren’t afraid to voice their concerns about issues affecting themselves or the community at large. We know from reports and documentation that they threw their support behind and became involved in many community organisations from sporting clubs, musical societies, fraternal societies, church societies, educational movements like the Mechanics’ Institute and even for some of the family, the Temperance movement.

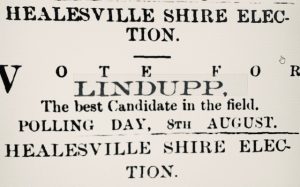

Many times they were at the forefront in the establishment of some of these organisations such as the Healesville Horticultural Society. Henry Jnr was one of the first subscribers to the Healesville Mechanics Institute and he ran for Council (unsuccessfully) at one point.

I believe the family was blessed with an innate sense of fairness, justice, and charity – qualities passed on by parents Harry and Mary who understood from childhood the meaning of being poor and living in hardship. As young immigrants to the Australian colony, they got a second chance and remained humble to end.

It’s been a pleasure researching and writing about Harry Lindupp Snr and his family. They were solid citizens, imbued with an indomitable pioneering spirit and dedicated to their local community.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Carol Yates for introducing me to Harry and his family and for allowing me to use her family history research. Her G Grandfather is John Lindupp and I hope she writes about him one day. It will be a fabulous story. Thank you also to the people at the Shoreham-by-Sea History Portal, the State Library of Victoria (SLV), the National Library of Australia and the wonderful TROVE, and Kae Lewis for the comprehensive website which tells the story of Charlie Hammond.

Author’s Note

I’m sorry if I’ve confused readers with my sometimes inconsistent and interchangeable use of the names Henry and Harry for both Snr and Jnr. I like the name Harry so I favoured its use over the more formal Henry particularly for Henry Snr. I noticed that John Lindupp was referred to as ”Jack” in Charlie Hammond’s pictorial diary but I decided to keep the more formal John for him.

Sources

Healesville and District Historical Society: A Pictorial History of Healesville (2013) – From a Village to a Town, Volume 1 1864 – 1920, Northeast Publishing & Roda Graphics Australia Pty. Ltd. Kinglake, Victoria

Lawrence, Susan (2000). Dolly’s Creek: an archaeology of a Victorian goldfields community. Carlton, Vic: Melbourne University Press

Maps of Talbot, Amherst, Gracedale sourced on-line via the State Library of Victoria

Melton, J. (Jim) (1986). Ships’ Deserters, 1852-1900 including stragglers, strays and absentees from H.M. ships. Library of Australian History, Sydney

Wilkie, Douglas (2015). Education in the Sink of Iniquity: A History of Education on the Goldfields of Amherst and Talbot from 1836 to 1862. Historia Incognita, Melbourne.

Victorian Newspapers from the 1850s-1900s sourced via TROVE and identified within the text.

Yates, Carol (2017) Personal Family History Research of the Lindupp Family

Endnotes

[i] Personal research of GG Granddaughter, Carol Yates, March 2017

[ii] Melton, J. (Jim) (1986). Ships’ Deserters, 1852-1900 including stragglers, strays and absentees from H.M. ships. Library of Australian History, Sydney

[iii] Presumably to the gold rush!

[iv] Melton, J. (Jim) (1986). Ships’ Deserters, 1852-1900 including stragglers, strays and absentees from H.M. ships. Library of Australian History, Sydney.

[v] Ibid

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] There is no record of Betty’s death but their father, Peter Walsh, is the only recorded parent of Mary and Eliza in the Irish Famine Orphan Records.

[viii] Information from Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Philip%27s_Church,_Sydney

[ix] This section on “Nuggetty Gully” is based on information contained in Carol Yates Research of March 2017 and my own current research.

[x] Immunization records held at the Talbot Historical Society show that three of the Lindupp children (George, Elizabeth and Mary) were vaccinated against smallpox in 1865 and in 1866 John received his at 11 months old. The records show that the family resided in Nuggetty Gully/Talbot. Vaccination for smallpox was compulsory.

[xi] Wilkie, Douglas (2015). Education in the Sink of Iniquity: A History of Education on the Goldfields of Amherst and Talbot from 1836 to 1862. Historia Incognita, Melbourne.

[xii][xii] I know it’s confusing. I’m confused too. Nuggetty Gully later became Talbot so I had read. Then I read Douglas Wilkie’s ‘The Sink of Iniquity …..’ and learnt that Back Creek also became Talbot later in 1862. So, was Back Creek earlier on Nuggetty Gully? I throw my hands up. I don’t know!!! I am assuming Nuggetty Gully, Back Creek and Talbot are all the same, at least all in the same area.

[xiii] The Argus, 25 April 1859 – Headed “‘BACK CREEK’ (From a Correspondent.) April 20, 1859”

[xiv] Wilkie, Douglas (2015). Education in the Sink of Iniquity: A History of Education on the Goldfields of Amherst and Talbot from 1836 to 1862. Historia Incognita, Melbourne. p. 132

[xv] The Argus, 25 April 1859 – Headed “‘BACK CREEK’ (From a Correspondent.) April 20, 1859”

[xvi] Ibid

[xvii] Ibid

[xviii] Murray, R., Taylor, N., & Shepherd, R. (1883). Clunes, Mt. Greenock and Talbot gold fields [cartographic material] / geologically and topographically surveyed by Norman Taylor and R.A.F. Murray; lithographed by R. Shepherd. Melbourne: Mining Dept.

[xix] Windsor, G. A & Noone, John & Bailliere, F. F & Victoria. Department of Crown Lands and Survey. (1866). Talbot Retrieved September 8, 2019, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-231000814

[xx] Carol Yates Research, March 2017 from A Pictorial History of Talbot – A Historic Gold Town, by the Talbot Museum Committee (1988). Talbot

[xxi] Lawrence, Susan (2000). Dolly’s Creek: an archaeology of a Victorian goldfields community. Carlton, Vic: Melbourne University Press

[xxii] Ibid

[xxiii] Ibid

[xxiv] Healesville and District Historical Society: A Pictorial History of Healesville (2013) – From a Village to a Town, Volume 1 1864 – 1920, Northeast Publishing & Roda Graphics Australia Pty. Ltd. Kinglake, Victoria

[xxv] From my Mother’s ‘family history notes’. It’s probably more accurate to say that the Lindupp family were ‘early’ residents in Fernshaw given the timing of their arrival in the area.

[xxvi] https://www.victorianplaces.com.au/fernshaw

[xxvii] The Healesville and District Historical Society, (2013) Images of Time. A Pictorial History of Healesville – From A Village To A Town, Vol 1 1864-1920, p104.

[xxviii] In 1991 IOR Victoria combined with the IOR in other states to form a National Health Fund. People wishing to join the fund were no longer required to sign a pledge to abstain from alcohol. In 2002 the IOR Health Fund was sold to HCF Health Insurance.

[xxix] https://www.australianrechabites.org.au/states/vic-rechabites/

[xxx] Stands for Manchester United Independent Order of Odd Fellows