Introduction

Coombes Church, West Sussex is famous for its medieval religious frescoes, discovered when a piece of plaster fell from a chapel wall during maintenance work in 1949. The Church, built into a hillside amidst lush pastoral surrounds has served congregations for nearly 1000 years in this beautiful part of the South Downs. For the Lindupp family it is an important historic landmark as two family weddings took place here in 1681 and 1709.

The Village of Coombes

In his 1923 book Off the Beaten Track in Sussex Arthur Stanley Cooke provides a charming description of Coombes’ village.

“Five houses and the little church comprise the village of Coombes. It is the place for a pastoral poet to dwell, if peace and unbroken solitude are what his soul delights in. The very road towards it gets grass grown and uncertain where to trend, and finally decides to leave it lying undisturbed in its hollow. If seclusion means peace, surely this is the home of peace. Its name is derived from the Saxon for a deep valley, ‘an expression perfectly suited to the situation.'”

A Saxon and Early Norman Church

Dating from the Saxon and early Norman period, the Church is a simple flint stone building, bearing humble adornments, probably reflecting the small rural community it served centuries back.

Cooke describes Coombes Church, West Sussex as:

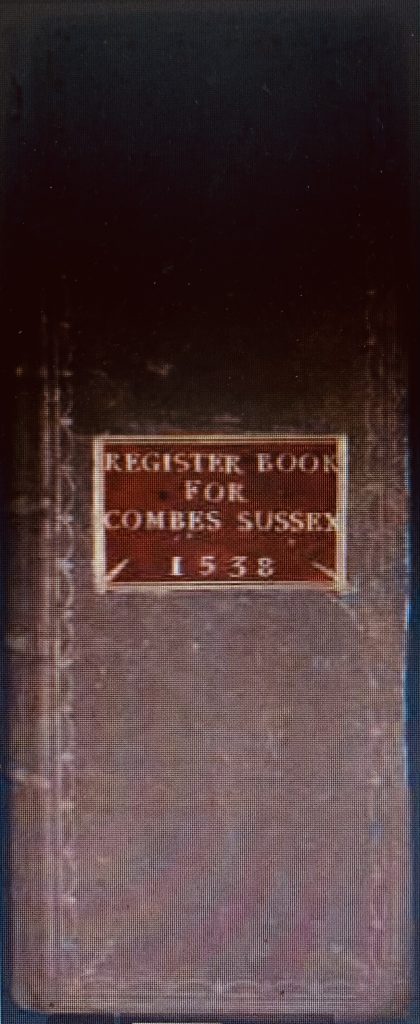

” … being Saxon or very early Norman. The south and priest’s doors, and the font, are all Norman. Perpendicular windows have been inserted, and there is a circular low side or ‘leper window’, splayed internally eastward, so that the alter could be seen. On the priests door are circular marks which maybe sundials, and there is some old stained glass. The chalice is dated 1588, and the register goes back to 1538, a very early date.”

The Leper Window

Leper Windows or Leper ‘Squints’ were common in medieval churches. These small windows were installed just above ground level so Lepers, who were forbidden from mixing with the general population, could stand outside and watch church rituals.

Leprosy came into Britain via soldiers returning from the Crusades.

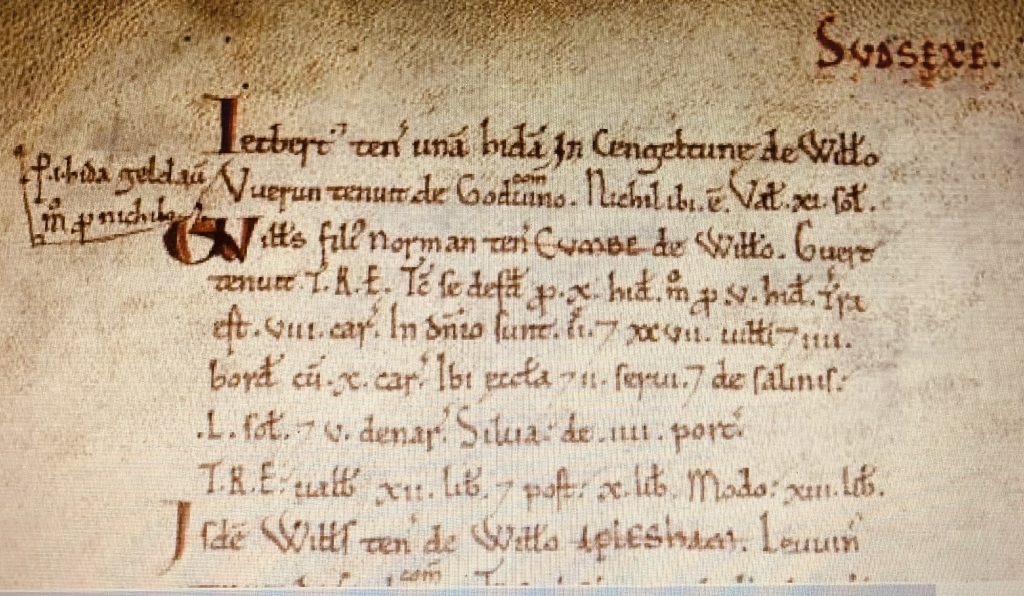

Coombes Church Older than the Domesday Book

Coombes Church, predates the Domesday Book of 1086 making the Church nearly 1000 years old or maybe even older. The Domesday Book now digitised and translated from the original Latin to English can be accessed via the National Archives UK.

Conveniently translated the entry for Coombes reads:

“William fitzNorman holds COOMBES of William. Gyrth held it TRE. Then it was assessed at 10 hides; now at 5 hides. There is land for 8 ploughs. In demesne are 2 [ploughs]; 27 villans and 4 bordars with 10 ploughs. There is a church, and 2 slaves, and from the salt-pans 50s5d, [and] woodland for 4 pigs. TRE it was worth 12l; and afterwards 10l; now 13l.”

This means Earl Gyrth owned the land and manor prior to 1066 with William Fitz Norman taking over twenty years later in 1086. ‘A Bit About Britain’ hints at 33 people living in Coombes village in 1086. Incredibly, that’s one more person than than lived there in 2021.

“By the time of Domesday, the manor was held by a William Fitz Norman (possibly a kinsman of the Conqueror) and consisted of 27 villani (villagers who owed labour service to the lord, but also farmed on their own account), 4 bordars (unfree peasants) and 2 serfs. The population peaked at 99 in 1931 and, according to the Coombe Farm website, was back down to 32 in 2021.”

Visiting Coombes Church,West Sussex

Travelling with my cousin and aunt, I knew what Cooke meant when we arrived in Coombes from Shoreham-by-Sea and walked up to the little Church through a field of plush carpet-like grass begging us to run barefoot. This was the “place for a pastoral poet to dwell” and the “home of peace”. Lush grass like this is such a rarity in Australia and to see it surrounding headstones was a unique experience. Rural cemeteries in Australia are often dusty dry places with weather beaten headstones and damaged grave sites. In fact, a wombat hole or two isn’t uncommon.

Protective Nettles

Apart from the soft lush grass, the other thing I loved about the Coombes churchyard were the prolific stinging nettles shrouding the headstones and graves. I thought how well protected these grave sites were. As the great classical herbalist Nicholas Culpepper joked (I think) in his early 1800s Complete Herbal:

“Nettles are so well known that they need no description; they may be found, by feeling, in the darkest night.”

While you probably wouldn’t go walking about Coombes churchyard at night feeling around for Nettles it’s worth remembering the old saying “Nettle in, Dock out”. Dock can usually be found growing in close proximity to Nettles and the juice of the Dock if rubbed into the affected area acts as an antidote to the Nettle sting. This is just one of Nature’s little balancing wonders.

The Medieval Wall Paintings in Coombes Church

Dating from the 12th and 13th centuries the wall art is extensive – covering the north, south and eastern walls of the nave and most likely the work of monks from the Lewes Priory in East Sussex. English Heritage listed Coombes Church a Grade 1 site on 12 October 1954, five years after the paintings were discovered.

The wall art designs include The Visitation, the Nativity of Jesus, Christ in Majesty and Christ delivering the Keys of Heaven to Saint Peter and the Book to Saint Paul.

These paintings are incredibly captivating when you see them up close and in person. One can only imagine what they looked like in their full glory nearly 10 centuries ago. It’s such a pity Cooke never got to see them when he visited the Church in the 1920s as they would have added to his delight.

Face Carving in Coombes Church, West Sussex

As well as the medieval paintings, Coombes Church has an intriguing carved face on the left side of the chancery arch. Carved faces or heads were common on corbels in medieval churches, but why only one in the Coombes Church? What did the carving mean or who did it represent?

Richard Halsey points out in his article Interpreting Medieval Corbel Sculpture that not every stone corbel is of the highest standard and it’s still not fully understood what messages stonemasons were trying to convey.

However, everything within a church has meaning and the carved face in Coombes Church simply wouldn’t be there if it had no meaning. The close up image has a distinctly human appearance and the slightly upturned lips and ‘soft’ eyes convey an air of benevolence. Maybe it was the image of the priest at the time, the main benefactor or an important person in the village of Coombes.

Why Was the Wall Art Painted Over in Coombes Church, West Sussex?

The religious upheaval caused by the rise of Protestantism over the 16th-17th centuries in England spelt doom for the original wall paintings. During this period the protestant movement began purging churches of all religious decoration and images as Puritans thought such ornamentation fostered idolatry.

Today one would consider the white washing an act of vandalism. The paintings had a simple purpose. They told bible stories to those who couldn’t read or understand Latin, the common Church language at the time.

Lewes Priory

Lewes Priory suffered dreadfully, mercilessly demolished bit by bit between 1535 and 1540 under the Dissolution of Monasteries Act, during Henry VIII’s reign. The Priory monks were probably murdered. Thankfully some lesser buildings still stand today and are an important part of England’s medieval heritage. The site is now a Grade 1 listed building.

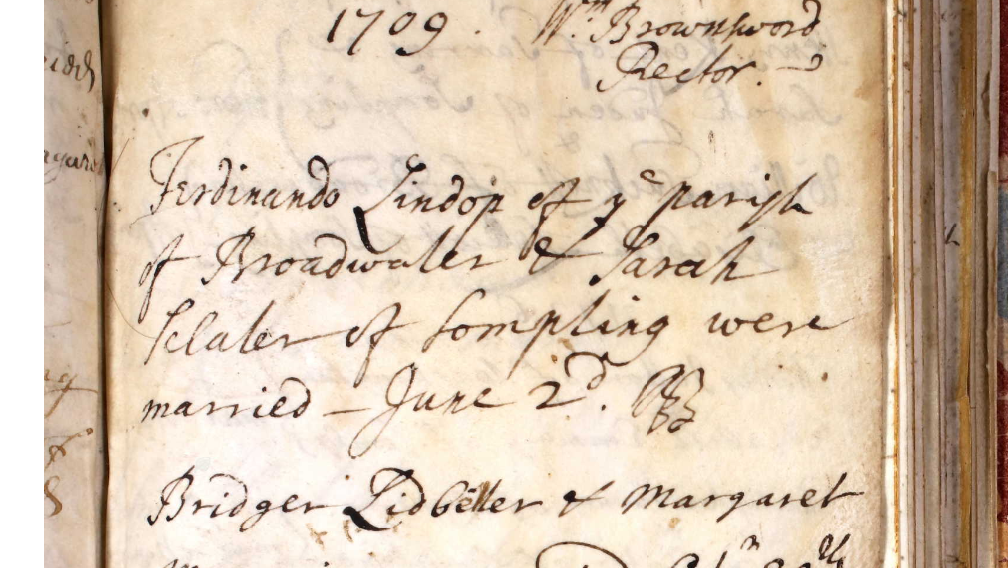

The Lindupp Marriages in Coombes Church, West Sussex

Ferdinando Lindupp and Anne Sylvester married in Coombes Church on 5 May, 1681 and 28 years later their son, Ferdinando, married Sarah Scatler on 2 June 1709. Both marriages are recorded in the ‘Register Book For Combes Sussex 1538’‘. Unfortunately Ferdinando senior never saw his son marry Sarah as he died in June 1700 at age 37. From probate records and other documents we can surmise that Ferdinando took Sarah back to Broadwater, Worthing (five miles from Coombes) where he farmed on land that later became site of The Swan Inn.

The site of the Swan can be tracked back to the late 17th century – a dwelling place, barn and 25 acres of land owned by Ferdinando Lindup, a yeoman of the area – a Yeoman being someone who works his own land. It eventually ended up in the hands of Richard Lindup, who built a more substantial property in around 1790. In 1842, the building became a lodging house and by 1849 it had become an ‘Inn’.

The field leading up to the Church was probably ablaze with summer wildflowers on Ferdinando and Sarah’s wedding day in June 1709. Some of these wildflowers may have been in her bouquet. Anne Sylvester marrying in springtime may have been fortunate enough to have local woodlands ablaze with bluebells and incorporated these in her bouquet in May 1681.

Country Weddings in the 17th and Early 18th Centuries

Having done some quick research on weddings in the 17th and early 18th centuries this is how I imagine the wedding day of the two Ferdinandos and their brides.

The Flowers

Like most country brides at the time Anne and Sarah wore flowers in their hair and carried informal bouquets of whatever fragrant herbs, flowers or greenery were in season. All collected from local roadsides, gardens and fields. Whatever they chose had meaningful symbolism to do with love, purity, fidelity and fertility.

Their bouquets probably included some of the following; wild roses, forget-me-nots, love-in-a-mist, scabiosa, yarrow, myrtle, honeysuckle, sweet woodruff, bluebells, ivy and wheat grass, all bound together with rope or ribbon. A love knot intertwined amongst the stems.

The Wedding Dresses

The wedding dresses were probably not new just their best dresses, but on this special day decorated with meaningful adornments. They may have added a frill or blue ribbon somewhere. Blue was and still is an important colour for brides representing trust, purity and fidelity.

Garters, were often blue, and worn by the bride just above each knee. As festivities got jollier and jollier and the couple retreated to the marital bed two groomsmen, NOT the groom, removed the garters and pinned them to their hats as a trophy.

The Wedding Banquets

There were no formal invitations to weddings like today. It was all word of mouth. If you were told about a wedding you could go and join in the feasting and dancing. It was an exciting time for a village and the whole community helped prepare the celebratory feast for the new couple and their families. There was an abundance of food including cakes, meats, fruits, drinks and other special treats.

The Wedding Cake

Of course there was a wedding cake or cakes. Around 400 years ago the tradition was to have two cakes one for the bride and the other for the groom. The bride’s cake was lighter with a pale covering while the groom’s was much darker and richer.

Children of Ferdinando and Sarah Lindupp

Sarah gave birth to 12 children; Thomas (1710-1729), John (1711-1770), Sarah (1713-1737), Charles (1716-1716), Richard (1717-1763), Henry (1718-1763), Ferdinando (1720-1721), Charles (1722-?), James (1723-1749), Edward (1727-1731), Mary (1729-1766), Edward (1734-1790). Seven or possibly eight children reached adulthood. The death record for Charles b. 1722 is proving difficult to find.

Sixth born Henry starts the branch of the Lindupp family which sees his Great Grandson, also Henry, sail to Australia to start a pioneering life first on the Victorian goldfields and then Healesville in the Yarra Ranges.

The story of Henry ‘Harry’ Lindupp, a merchant seaman from Shoreham by Sea, can be read here.

What a fabulous collection of personal stories and stunning pictures, all wrapped up in a history lesson. Such a privilege to read your blog.

Thanks so much Jo. It was such a beautiful place to visit.

Really Great blog & post. I am a little biased though Ferdinando and Sarah are both ancestors. I think the first Ferdinando (born I believe 1610) & his wife Hester Glasse originally hailed from Staffordshire, possibly migrating south to Sussex during the Civil war period in England… maybe. Thanks for the post, such great information & Coombes really must visit!!!🙂👍 Trev Lindupp

Hi Trevor

Thank you! So pleased you enjoyed the post. Yes I think you are right about our first Ferdinando and his wife Hester hailing from Staffordshire and possibly migrating south to Sussex. I would love to be able to pin it down. My Grandfather’s mother was a Lindupp – Elizabeth. She was born on the Victorian goldfields to Henry (Harry) Lindupp and his wife Mary Jane Walsh (an Irish Famine Orphan). So great to hear from a Lindupp!

Thanks again and cheers

Sue

Just discovered this great site! I also have pottered around (far less professionally..) the area, having Lindup ancestors, and I have put what I can find onto WikiTree for posterity. It’s the first time I’ve encountered Harry the pioneer, and it’s lovely to find so many more relatives down under.

The great Ferdinando mystery I also understand, having got no further than anyone else [see wikitree.com/wiki/Lindup-68 for my ‘dead end’]. A naughty thought: did our Ferdi grab the family silver and scarper to the south coast – he obviously had enough cash to set up in business and property… It’s rather a long way to travel, but there was some trouble and strife at the time. Perhaps he thought the coast was the best place to be, with maritime pickings to be had, and a quick escape route if he was rumbled.

On another subject, last week I was researching a completely different family in Broadwater area – the Congreve-Pridgeons, because both they and I were and are keen bellringers, and I had wondered why Robert of that ilk rang bells here in Oxford way-back. I found that he rang a long peal with a Lindup… and here we go again! In trying to trace the origin of the bellringer Edmund Henry Lindup 1870[Lindup-90] back to the Ferdinandos, and failing, I stumbled on this site, and the claim mentioned in the Coombes article (super bit of story-telling there) that Henry “Harry” the gold-rush pioneer [Lindupp-3] was the great-grandson of Henry Lindup 1718 [Lindup-61] the son of Ferdi and Sarah S[c]later. This being a minefield of similar names and dates, I wondered if anyone can shed some light on this ggson link and how it was arrived at? As you can see, the best I can do currently is a fairly firm shot at William Lindupp 1801 [Lindupp-23] as Harry’s dad (from the 1841 census).

Just to round off, if anyone out there also updates WikiTree (labour of love, eh?) please let me know. Perhaps we can arrange to put up some of the photos if we have right permissions. You can see a few other WikiTree profile-managers names as you move around the Lindups.

One caveat with the WikiTree ID’s mentioned above – a couple of these might have to have spellings changed p to pp or vice versa, if we discover actual baptised names that are different from the LNABs we have – the LNAB-based ID’s will then change but the system will retain a memory of the old one so you can still get there. (I hope I’ve got all the above ones right!]

All best,

David

Thanks David glad you enjoyed my Lindupp story. I rather like your theory about Ferdinand. As you say the minefield of similar names and dates is a nightmare! I’ll check out WikiTree. I mainly use Ancestry.com as a base to help populate my tree, but I must have another look. The Lindupp family moved to Healesville in the 1860s where they became a prominent pioneer family. I think Henry made some smart moves on the goldfields and in Healesville (both far away from the merchant navy and the sea). Good to hear from you! Please stay in touch.

Cheers

Sue