Air Fatality in Canberra Scars an Historic Day in Australia

Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Faces Scrutiny After Plane Crashes on the Opening Day of Australia's Parliament House in Canberra, 9 May 1927.

Introduction

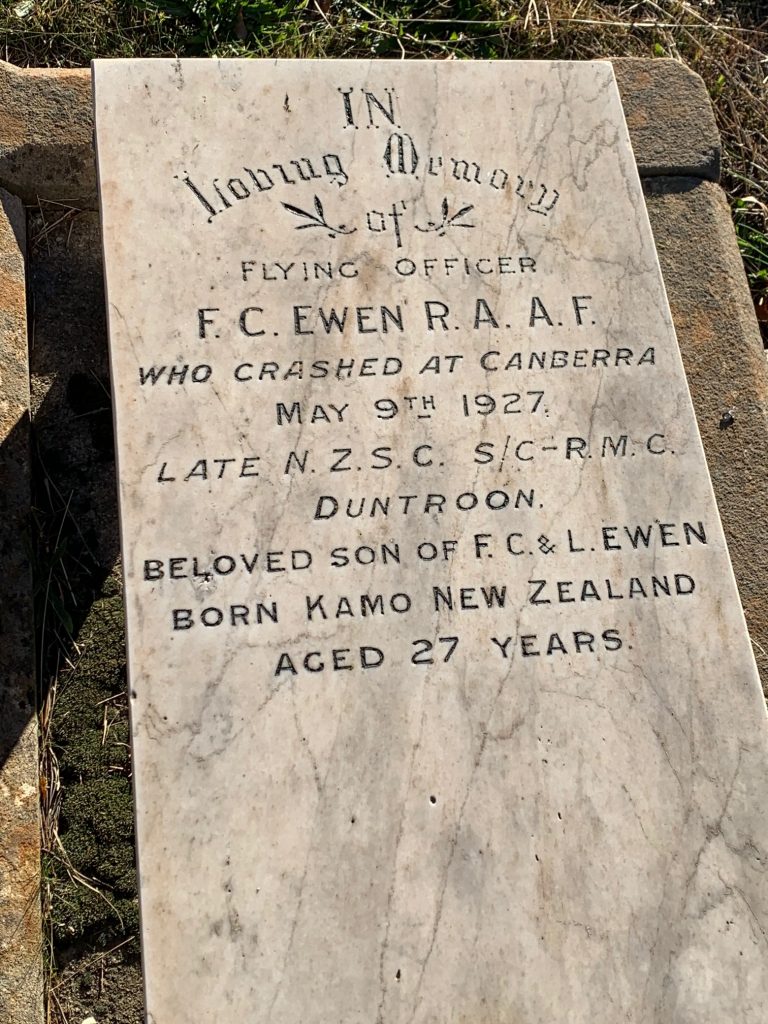

An air fatality in Canberra in 1927 left a permanent yet hidden scar on an historic day in Australia. Flying Officer Francis Charles Ewen died tragically when his plane swept from a flying formation and nose-dived into the ground during a military review on the opening day celebrations of Parliament House in Canberra on 9 May 1927.

The day was meticulously organised to showcase Australia’s capital city and the new seat of federal government amid the pomp and pageantry of a Royal visit and a gathering of the nation’s top brass. What started with excitement and bugle fanfare ended in sorrow with a bugle playing the sombre strains of the ‘Last Post’.

Ewen was accorded a funeral with full military honours two days after his death and is buried in the graveyard of Canberra’s oldest Church, St John the Baptist in Reid.

This is a story of a dashing pilot and the crash that took his life and brought into question the safety procedures and integrity of Australia’s fledgling air force in the 1920s.

Flying Officer Francis Charles Ewen (1899-1927)

Francis Ewen was born on 27 July 1899 in Auckland. He died aged 27 in 1927[i]. An eerie numeric synchronicity perhaps. He received his education at Auckland Grammar School before attending the Royal Military College Duntroon (RMC) from where he graduated as a New Zealand cadet in December 1920.

Ewen appeared to be an above average cadet receiving grades between “Good” and “First Class” in all aspects of training. He played in the first XV rugby team for RMC and excelled as an athlete.

“Determined character, should make a good officer” were the words penned by RMC Commandant Major General J. G. Legge on Ewen’s final report signed 13 December 1920.[ii]

Returning to New Zealand after graduation he served as an officer for over five years with the New Zealand permanent forces until March 1926 having applied to join the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF).

By 15 April 1926 he had received his commission as a Flying Officer with the RAAF and was stationed at Point Cook in Victoria where he was described as a popular officer. (The Sun, 10 May 1927, p12)

Air Force and Flying Experience

Ewen had been with the RAAF for less than 13 months when he was tragically killed on that fateful day in May 1927. According to his service record obtained from the National Archives of Australia (NAA) his role with the Air Force was more administrative than flying.[iii]

On 1 December 1926 he was made Assistant Adjutant at Point Cook and then Adjutant on 14 March 1927.[iv] In less than eight weeks he was killed flying an old reconditioned and overhauled WW1 fighter plane.

His records say that while he was with the New Zealand Staff Corps he attended “ … a course of instruction at Wigram Aerodrome in Duties of an Observer, Theory of Flight, Rigging, Aero Engines, etc and a little flying.”[v]

His flying experience at Wigram included:

| Flying Primary Dual Control | 4hrs 10mins |

| Solo | 13hrs 50mins |

| Secondary Dual Control | 1hr 35mins |

| Casual | 3hrs 15mins |

With limited flight training and hours (in Avros only), Ewen was interviewed and passed medically fit for full flying duties. He was recommended for appointment as a Flying Officer in an Air Board document in March 1926. His appointment later confirmed in the November after receiving a “Distinguished Pass (79.9%)” in “Course A” and described as, “An excellent officer. Keen and industrious”.

After the crash the Canberra Times reported Ewen was a “qualified pilot, a strong man, and of sober habits”. (Canberra Times, 13 May 1927, p2) In little over a year at Point Cook, he had managed to build up his flying hours, qualify as a pilot, and be considered worthy of participating in the first RAAF mass ‘fly past’ at a major ceremony.

The Aircraft

Ewen was flying a Scout Experimenter (S.E.5A A2-24), an old WW1 fighter plane, flown to Canberra from Point Cook for the celebrations. Known in later years as the ‘Spitfire’ of WW1, it was one of the planes surplus to Britain’s needs after the Great War and along with 127 other aircraft, it formed part of the Imperial Gift in 1919.[vi] These British planes were the foundation of the new RAAF.

According to some pilots S.E.5A’s were one of the easiest planes to fly. They were also quick, had good manoeuvrability and were effective fighters. Landing however could be difficult.[vii]

Cecil Lewis, an ace British WW1 pilot, said the aircraft was reliable, quick, and easy to manoeuvre. The hazard, he recalled, was not being able to get out of the plane, not being able to jump, and not having anywhere to go. “You just had to sit tight and take what came. You were wedged into your cockpit.”[viii]

This seemed to be evidence that no matter if you had a parachute or not, it was impossible to get out of the cockpit and jump. However sitting tight in an aircraft in 1917 air battles meant accepting the fact that you were without a parachute and you were “wedged into your cockpit” because of the bulky high-altitude clothing. Flying Officer Ewen was not wearing a bulking flying suit on the day of the crash.

Could Ewen Have Bailed Out?

The question why Ewen didn’t release his parachute and jump was asked by Air Force authorities after his accident. Baling out would only take a few seconds involving him releasing the lap-belt, standing up and jumping. No need to do up straps before baling as the parachute is firmly secured to the pilot’s body. However, with Ewen’s plane heading straight to the ground from 1000 feet he would only have split seconds to act. If he could have, levelling the plane was a better option. So why didn’t he?

The Crash

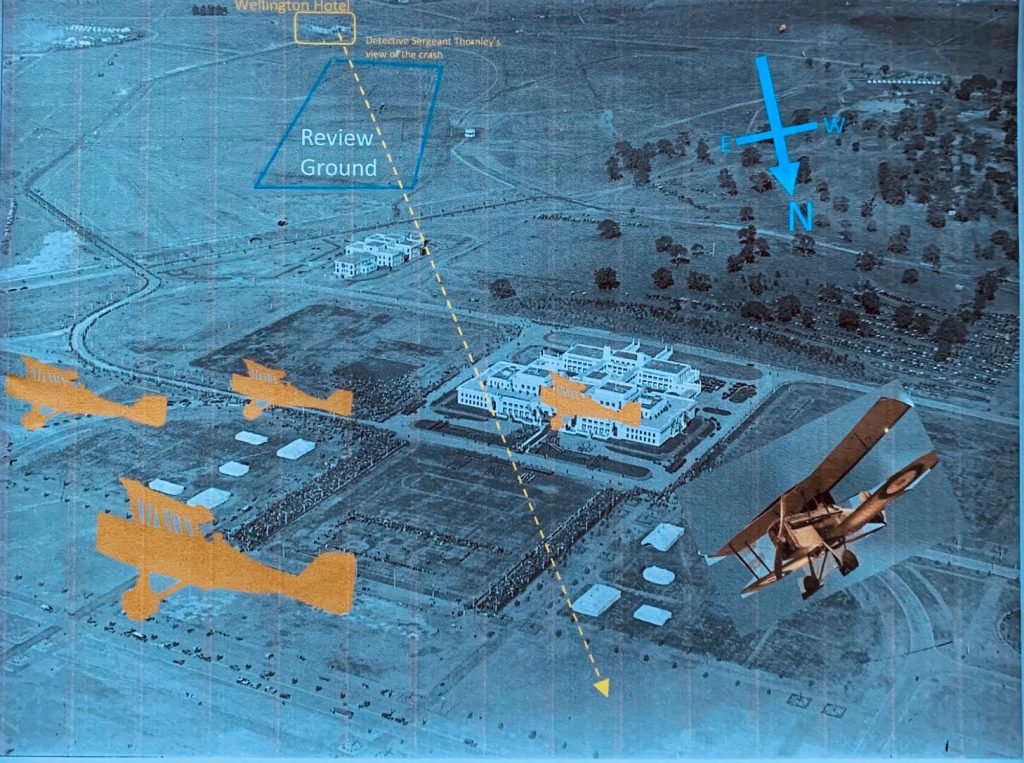

The crash occurred at around 3.20pm in the afternoon when the planes were out for a second time. This time the aerial display was to coincide with a military review taking place on the eastern side of Parliament House with the old Hotel Wellington visible in the distance.

The Duke received the salute from troops while seated on a magnificent black charger and the Duchess viewed proceedings from a special rotunda with other distinguished guests. Fortunately, from where they were positioned, the Royal couple didn’t see the crash.

Unfolding of the Air Fatality in Canberra

Fifteen planes flying in three groups of five were each making a “V” formation. Ewen was flying in “B” Group. As the planes flew in their formations about 440 yards (402 metres) from the Hotel Canberra (now The Hyatt) observers said that Ewen’s plane was flying lower than the other planes and also on the outside of his group of five.

As the planes turned towards Parliament House, Ewen’s plane stayed out as if giving way to the others. It started to swoop sideways and appeared to suddenly stop in the air and then nose-dive at a frightening speed to the ground. There are varying reports of where the dive started. Some say it started from around 500 feet others say from 1000, 1200 or 1500 feet. The most reliable witness is Flying Officer Sidney James Moir who was flying behind Ewen with the benefit of his altimeter. He said they were at an altitude of just over 1000 feet.

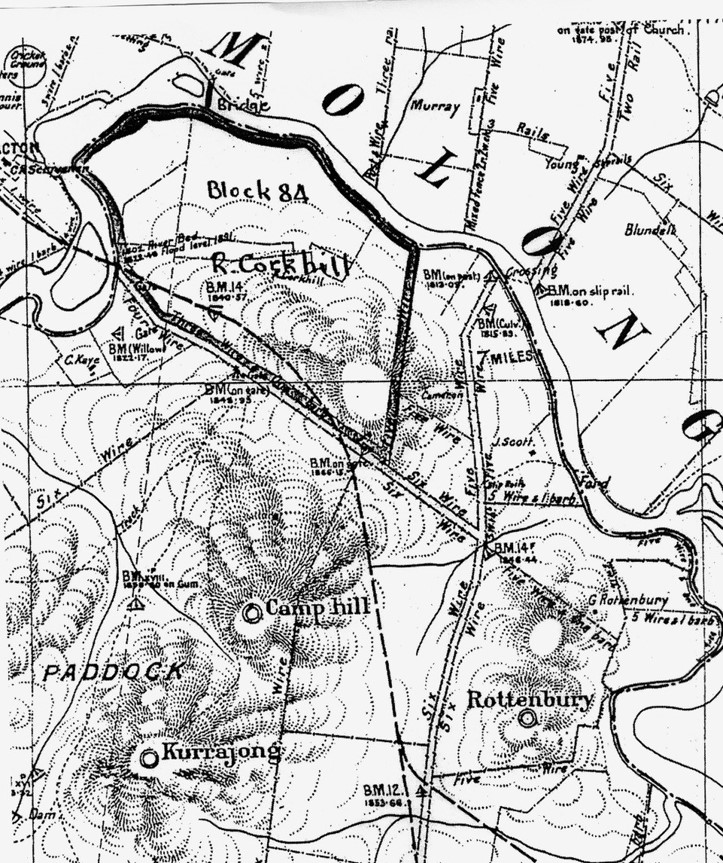

The plane crashed on Corkhill, a small rise visible from the front of Parliament House and 600 to 1000 yards (914.4 metres) away, in the vicinity of where the National Library and Reconciliation Place are today. A history researcher in Canberra using both modern technology and historical maps has located the scene of the crash with a great deal of accuracy. The exact location was revealed on a National Trust (ACT) heritage walk in Canberra in April 2022.

When the plane came hurtling down there were fears for a moment that it would hit the YWCA tent in the camping ground but it missed by 50 yards crashing deep into the ground and sending up a cloud of dust and a sheet of blue flame. Nearby campers fled away in terror.

Rushing to the scene, campers and police found Ewen half buried in the wreckage with horrific injuries including a badly crushed head but still alive and strapped to his seat. His right foot was entangled in the rudder controls and his head crushed against the dashboard. He appeared to have something to say but couldn’t articulate according to a witness. (Daily Telegraph, 10 May 1927, p2)

Parachute Confusion

First responders claimed that Ewen had unsuccessfully tried to use his parachute as it was found attached to his body and half opened.

New information provided from 3 Squadron (2 December 2021) said that journalistic inexperience at the time led to confusing statements about Ewen’s parachute. The fact is, that during flight Ewen was sitting on it, the parachute pack taking the place of his seat cushion. Over the top of the parachute harness was his safety belt, connected to the seat structure. The safety belt was a simple lap belt; the SE5A didn’t have shoulder seatbelts as later planes did. When he crashed Ewen was still strapped to his seat so therefore he was still sitting on his parachute.

After cutting Ewen free from the wreckage and with his body covered in blood and oil he was taken to the Telopea Park School emergency military hospital. From there he was taken to Canberra hospital where he died at 7.00pm that night. (Armidale Chronicle, 11 May 1927, p4)

It was probably during the rescue, that Ewen’s parachute became undone, rather than him trying to release it. When rescuers arrived they would have found Ewen “strapped in”. The first thing immediately seen would be his parachute harness which they would cut first. However, they would have soon found that Ewen was actually being held in by his “lap” seatbelt. Once the seat belt was undone Ewen could be lifted out of the wreckage leaving the parachute behind.

The impact of the crash itself or the efforts of the rescuers could have easily popped the parachute covering, which is designed to pull apart. Signs of the parachute silk probably prompted press reports that Ewen had tried unsuccessfully to release his parachute.

The observation that Ewen was covered in oil may, to the untrained eye, indicate that there was a major mechanical issue with the plane. More likely however, Ewen was probably doused in oil during impact when the engine oil tank, located on the floor of the plane in front of the pilot’s feet (see number 50 on this diagram.), ruptured on impact.

Apart from the machine gun which was found “practically undamaged”, the rest of the plane was smashed to pieces, the propeller splintered, the engine broken in half and the wings and fuselage shattered. (Singleton Argus, 12 May 1927, p2)

Eye-Witness Accounts of the Air Fatality in Canberra

Constable George Williams who had been standing half-way down the hill was one of the first on the scene and said:

“When the planes were on the turn the S.E.5 kept well out apparently to give the others more room for turning. The man who was with me said: ‘Look at this chap. He seems to be doing some stunting.’ I looked again and it seemed to me that the pilot was in trouble. The machine swayed, a little, and suddenly nosedived. It crashed with terrific impact. When I arrived the pilot was still strapped in his seat. I had to get a knife and cut him away. His right foot was still in the rudder control, and the blood on the dashboard showed that he had struck his head heavily. Hundreds of people quickly gathered around the ‘plane, which was completely wrecked. The engine was merely a ball of twisted metal. The left wing was smashed beyond recognition and the tail almost severed.” (Herald, 9 May 1927, p1)

Other witnesses provided vivid descriptions of the impact.

“The plane which dived with terrific force, was smashed to atoms.” (Chronicle, 14 May 1927, p54)

“The machine bit its way into the earth, and was completely wrecked; its wings crumpled, its woodwork smashed to splinters, and its cockpit a wild tangle of wood and steel.” (Armidale Chronicle, 11 May 1927, p4)

“Scarcely a unit of the wings, fuselage, or engine is intact,” said the Daily Telegraph. (Daily Telegraph, 10 May 1927, p2)

One eye-witness, Mr R. Maurice Cantor, an importer, and warehouseman from Sydney said:

“There were few people, near the scene of the smash. The plane landed with a terrific crash. The whole of it except the tail was reduced to splinters. There was nothing left of the propeller and wheels. You could not tell where the pilot’s seat had been. It was a mass of tangled aluminium. Fortunately, the machine did not land among the motor cars. As it was there was fear of the petrol, leaking from the tank, catching alight.” (Daily Telegraph, 10 May 1927, p2)

Mr Cantor’s account was published in more detail in the Sydney Morning Herald:

“It’s most unnerving feature was the suddenness with which it occurred. The machine just prior to the accident was flying at a height of about 500 feet, and it appeared to be behaving in perfect order. Then it appeared suddenly to dip forward and fall heavily towards the ground. In doing so it swerved slightly to the left, with the result that the left wing struck the ground simultaneously with the nose.”

A fortunate aspect of the tragedy was that the crash was seen by no more than perhaps one hundred people. The pilot at the time was flying on the opposite side of Parliament House to the review, and this, coupled with the fact that he was flying at a comparatively low altitude, resulted in his not coming under the notice of the thousands of people whose attention was concentrated on the review ground. Although the noise of the crash was exceptionally loud the bulk of onlookers did not appear to hear it.

The pilots of the other machines showed remarkable devotion to duty. For a few minutes their natural anxiety concerning their comrade made them circle above the scene of the disaster, but they then carried on with their Programme until its conclusion.” (SMH 10 May 1927, p13)

Another eye witness, Mr Walter Witters a visitor to Canberra was close to the scene of the crash and said he:

“… watched the ‘plane closely, and it seemed to be in trouble. It turned towards Parliament House, and stopping suddenly, plunged down nose first. I thought he was going to loop the loop but he came down too low, and then fell.” (Armidale Chronicle, 11 May 1927, p4)

Poor Mrs Maria Grazia, wife of Angelo Virgona proprietor of the Orpheum Picture Theatre in Sydney was so shocked by the sight of the crash that she died of heart failure. (Daily Examiner, 12 May 1927, p5)

In a sweeping and detailed account of the disaster the Sydney Morning Herald said:

“The ‘planes this morning were in the air very early, and their flying in formation was favourably commented on. They were out again this afternoon very early for the review, at which they were to take part. Around and around Parliament House their movements took them, and the crowd was entertained while waiting for the Royal couple. They had been in the air for an hour flying in formation of fives, forming the letter “V.” One of the ’planes in one of the groups appeared to fall behind its companions, and then appeared to be attempting to spurt to catch up to those ahead. Suddenly this ‘plane appeared to make an upward movement, and almost immediately turned straight towards the earth from a height of 500 foot, rushing at an alarming rate downwards. The pilot seemed, as he neared the earth, to be trying to make the ‘plane volplane, but its downward career continued, and he hit the earth with a tremendous report and turned over. The ‘plane came down on what is known as Rottenbury Hill[ix], almost in front of Parliament House. Just over the brow of the hill from which the battery this morning fired the salute, and just beyond the tents of the Y.W.C.A. When the ‘plane hit the earth a cloud of dust shot up fully 50 foot. There was an immediate rush of people from the parade ground to the scene. The field ambulance rushed to the spot.” (SMH, 10 May 1927, p13)

Where Did Ewen Crash, Rottenbury Hill or Corkhill?

There was some confusion in reports as to where the plane actually crashed. The confusion was probably a mix up with the names and geographical locations of the hills in question by interstate reporters not familiar with the area.

Some reports say Rottenbury Hill and others say Corkhill. Eye witness accounts say the plane came down about 600-1000 yards in front of Parliament House not far from where the 21 gun salute took place during the morning ceremonies. The salute was fired in front of Parliament House and is visible in the original film footage released by the National Film and Sound Archives (NFSA).[x]

An expert observer, a Detective Sergeant from Sydney, Thomas Thornley, saw the crash unfold from the verandah of the Wellington Hotel, which lies south-east of Parliament House. He said:

“I was on the verandah of the Wellington Hotel, watching the review and a number of planes flying east in formation. I noticed one machine pointing north when it suddenly swooped down, and its right side seemed to be canted towards the east. I lost sight of it behind Parliament House just after it appeared to be nose-diving.” (Mercury, 11 May 1927, p9)

Detective Sergeant Thomas Thornley’s position at the Hotel Wellington looking westward and his account of Ewen’s plane peeling from the formation and falling behind Parliament House, confirms Corkhill as the likely crash site.

Corkhill[xi] was located in front and ever so slightly west of Parliament House. Rottenbury Hill however is to the east of Parliament House and within view of the review grounds. Thousands of people could have witnessed the disaster if the crash happened on Rottenbury Hill. Reports say the accident was not seen by the Royal Party who were at the military review at the time.

Corkhill, named after the prominent pioneer family who farmed the area, was more a rise than a hill and was in front of Parliament House and near the Molonglo River. Many people stood on this rise to watch the opening celebrations in the morning. It was removed in 1962 to improve the view of the Lake from the steps of Old Parliament House. The earth from Corkhill was used in the foundations of the Commonwealth and King’s Avenue Bridges and for levelling the lakeside area.[xii]

The Coroner’s Inquest into the Air Fatality in Canberra

If the military chiefs thought they could bully Mr John Gale, the 95 year old Coroner conducting the inquiry into the death of Flying Officer Ewen, they were wrong.

RAAF’s Initial Lack of Cooperation with the Coroner

The military wanted the inquiry held at Duntroon, but Mr Gale insisted the inquiry must be held at the Canberra Hospital where the body lay. Whether through military bullheadedness or an inflated perception of their status, the military authorities issued an ultimatum and refused to attend as witnesses unless the inquest was held at Duntroon.

Mr Gale ignored this imperiousness, called their bluff, and replied in very plain terms: “The military authorities were supreme amongst the soldiery, but they had no control of civil law.” He reiterated that the inquest would be held at the hospital, “ … and that the witnesses from Duntroon would fail to attend under peril of process to compel their attendance.” (Muswellbrook Chronicle, 3 June 1927, p4)

The inquest was held at the Canberra hospital on 10 May 1927 and military witnesses attended.

A Rushed Inquest

The Inquest according to the ‘Cootamundra Herald’ only lasted a few minutes before a verdict of accidental death was recorded by Coroner Gale. Officials were anxious to get the inquiry over quickly but gave no reason for the rush.

It was carried out with “unseemly haste” said the Daily Telegraph in Launceston, with no one there to ask pertinent questions about the machine’s soundness. (Daily Telegraph, Launceston, 12 May 1927, p4)

Usually in a case where the mechanical condition of a machine is likely to be questioned, the relatives of the crash victim are represented by Council, but the Ewen inquiry was held without relatives or their representatives being present. (Cootamundra Herald, 11 May 1927, p1)

Inquest Witnesses

Several witnesses appeared before Mr Gale, including the medical officers who attended the patient at the scene of the crash and later at the hospital; the chief mechanic and the pilots who saw Ewen’s plane go down.

Dr R.J.W Malcolm, the temporary medical officer said that when Ewen was brought to hospital he:

“ … was conscious but suffering severely from shock. There were compound fractures of the right and left arms and left thigh. The ribs were fractured and there was a large wound on the chest and lacerated wounds on other parts of the body. His death which occurred at 7 o’clock was due to shock following his injuries.” (Chronicle, 14 May 1927, p54)

Arthur Poole Lawrence, Director of Medical Services, R.A.A.F. who arrived at the scene shortly after the crash had a similar view to Dr Malcolm.

Flight Lieut. Ellis Charles Wackett, R.A.A.F, the principal witness and chief mechanic, who was at the review ground when the accident happened said he saw Ewen’s plane leave the formation and fall steeply before it disappeared from his view.

The same officer examined the plane wreckage to determine if there were defects with the controls declaring there was nothing to show that the accident was due to a defect.

Wackett said that there might have been several reasons for the crash, but he could not say what was the cause. He said the machine was in perfect order and “ … had been carefully examined before it left Melbourne a week ago.” (Cootamundra Herald, 11 May 1927, p1)

He didn’t appear to mention that the aircraft had also been repaired and overhauled at Cootamundra on its way to Canberra after a forced landing caused a tyre to blow and the plane to flip and land upside down.

Flying Officer Sidney James Moir (No. 3 Squadron) in giving evidence said that:

“ … he was flying slightly above (and behind) Ewen at an altitude of just over 1000 feet. They were turning into squadron formation to give the salute. Ewen’s plane left the formation, suddenly divided (sic) to earth.” He also said: “… he had no idea of the cause of the accident. If Ewen had had engine trouble he had ample room in which to right his machine.” (Canberra Times, 13 May 1927, p2)

Flying Officer Howard Bowden-Fletcher (who was flying in the plane with Moir) also gave evidence and said:

“… he noticed Ewen’s machine leave the formation in a stalling turn, which was continued in a further half turn to the ground. Ewen’s formation had just completed a turn, and it appeared that he stalled in doing so. Under ordinary circumstances he had every chance to pull out. Ewen had been in the air for about two hours, and after that length of time in the air a pilot was apt to grow tired.” (Canberra Times, 13 May 1927, p2)

It can be dangerous if a plane goes into a wing-lift stall where the speed of airflow over the wing falls below the minimum speed and the airflow becomes turbulent, greatly reducing the lift of the wing, and the plane suddenly drops.* In most cases pilots can recover from this with practised manoeuvres. Flying Officer Bowden-Fletcher believed something was wrong with Ewen which prevented him from pulling out of the stall. Interestingly he seemed to think that Ewen may have been drowsy or ‘asleep’ at the controls after being in the air for two hours. But, why weren’t other pilots affected by the lengthy time in the air?

* James Oglethorpe 3rd Squadron, Sydney.

Coroner’s Verdict of the Air Fatality in Canberra

After hearing the evidence, Mr Gale delivered a verdict of accidental death adding:

“This is one of those inexplicable happenings which cannot be explained by experts or others. The deceased was alone in his machine, and his secret has died with him; no one is to blame.” (Richmond River Express and Casino Kyogle Advertiser, 11 May 1927, p3)

The ‘Cootamundra Herald’ reported further comments made by Gale relating to the machine:

“There was nobody to blame, and there is nothing to show there was any defect in the machine. On the contrary the evidence showed it to be in good condition.”

Coroner Gale’s verdict as officially recorded says Francis Charles Ewen died in Canberra Hospital on 9 May 1927 from:

“Effects of shock, result of injuries accidentally received through the nose-diving to the ground of an aeroplane he was manoeuvring.”[xiv]

Under pressure after a series of airplane accidents over the week in Canberra, Air Force authorities probably breathed a sigh of relief when they heard Mr Gale’s conclusion, “ … no one is to blame.” And also importantly, the machine wasn’t to blame.

One of the mishaps happened on 7 May in the lead up to the celebrations. A plane developed engine trouble hundreds of feet above the ground and, “… after spluttering badly for some time, the engine suddenly ‘seized’ and stopped.” The pilot Flight Lieutenant McGillivray made a heavy landing in a lightly wooded gully beyond Eastlake where the plane stayed until an air mechanic could install a new engine or retrieve what hadn’t been broken. A standard procedure in those days.

The rushed inquest into Ewen’s death led to a wave of a skepticism in Canberra and beyond. Brisbane’s Daily Standard had a headline of “Policy of Hush. Death of Aviator at Canberra. Public Inquiry Urged.” The accompanying article said:

“Amazement was expressed at Canberra yesterday afternoon when it was disclosed that the inquest into the death of Flying Officer Ewen had been held. It was confidently expected that at least some little time would be allowed to elapse before the legal seal was placed on the tragedy, so as to allow relatives or friends of the dead aviator to attend.

The coroner returned a verdict of accidental death, attaching no blame to anybody. He could hardly have given any other verdict in the short span of time allowed for the investigations. It was considered when the inquest was concluded that many important aspects of the tragedy had been entirely overlooked. The fact that there had been eight other crashes at the aerodrome since the arrival of the squadron last week should have repaid at least some inquiry.” (Daily Standard, 11 May 1927, p6)

The article goes on with the question:

“Was the machine safe and sound? The opinion of the coroner that the tragedy was one of the inexplicable events which could never be accounted for by experts hardly coincides with the rumours than men of the Air Force stationed here had their morale considerably affected by the long sequence of smashes and the lack of confidence in the aeroplanes.”

And another question raised in the article:

“The fatal plane crash at Canberra was the eleventh since 1920, and Flying Officer Ewen’s death was the seventeenth in that time. Is this an indication that all is not as it should be in the Royal Australian Air Force? This question was warmly discussed in flying circles yesterday. The opinions expressed were sufficiently divergent to indicate that an inquiry into the whole question is essential, if only to satisfy the public doubts. Though the Air Force professes to be satisfied with the present state of affairs, it is understood that other branches of the Defence Force would welcome an exhaustive public inquiry into the whole question of aviation.” (Daily Standard, 11 May 1927, p6)

Was There an Air Force Cover Up of the Air Fatality in Canberra?

Immediately after Ewen’s crash the Air Force went into damage control. His accident added to the heavy toll on life, limb and machine that had beset the RAAF since its establishment in 1921 and more so in the recent days and weeks. People wanted an explanation. They wanted answers.

Was our RAAF jinxed? If you include the deaths of Captain J. Stutt and Sergeant A.G. Dalzell who were lost in Bass Strait while searching for a missing schooner in July 1920, 17 airmen had lost their lives in fatal crashes in seven years. (Herald, 10 May 1927, p5)

The statistics look even worse over the 15 month period from February 1926 to May 1927 when 12 airmen lost their lives. And even worse over a 19 day period from 21 April to 9 May 1927 when 5 aviators lost their lives.

Not three weeks before Ewen’s death four pilots perished during a fly past in Melbourne for the Royal couple. A crash witnessed by the Duke and Duchess and thousands of Royal wishers. Five deaths in 19 days. Five families wanting answers.

The List of RAAF Casualties 1921-1927

The list of accidents since the RAAF’s inception on 31 March 1921 to the time of Ewen’s crash on 9 May 1927 included:

- April 6, 1921: Corporal B. Whicker killed at Laverton when his Avro machine crashed through engine failure.

- March 5, 1925: Flying Officer S. E. Mailer killed and Flying Officer A J. Charlesworth injured when their Avro machine crashed at Point Cook owing to loss of control by Pilot.

- February 11, 1926: Flying Officer P.M. Pitt. and Photographer W. E. Callander, killed in DH9A crash at Canberra when landing.

- February 19, 1926: Cadet Albert John Greenwood killed at Point Cook when his SE5A overshot a landing and crashed.

- June 3, 1926: Cadet Aubrey H. Percival, killed at Point Cook through losing control of Avro (A3-27) machine and crashing from a height of 2000 feet.

- July 1, 1926: Flying Officer W. A. Holtham and Cadet Thomas Stuart Watson, killed near Point Cook in an Avro training machine through suspected engine failure causing engine to nose dive.

- September 5, 1926: Sergeant Ernest Brian Eball, killed when his DH9 (A6-17) crashed while attempting a forced landing near Geelong in a storm.

- February 13, 1927: Cadet Alexander Dix, killed Point Cook when his SE5A crashed owing to error of judgment.

- April 21, 1927: Flight Lieut Thornton, Flying Officer Dines, Sergeant Hay and Corp. Ramsden, killed when two DH9 machines crashed in mid-air through error of judgment when flying in close formation.

- May 9, 1927: Flying Officer F. C. Ewen, killed at Canberra in SE5A machine through losing control. [xiii]

In Ewen’s case the Air Force seemed too quick to claim that the cause of the crash wasn’t the machine, but the pilot. This seemed to be a standard official line according to Captain Geoffrey Hughes, President of the Australian Aero Club, NSW.

RAAF authorities suggested that Ewen must have had a fainting fit or a heart attack, otherwise he would have levelled the plane or opened his parachute and jumped. It certainly wasn’t a fatal heart attack because Ewen was still conscious immediately after the crash. Could he have had a fainting fit? If so what could cause a reduction of blood flow to his brain?

Quick Disposal of Wreckage

Not only was the inquest rushed, but the Air Force wasted no time in disposing of whatever evidence may have remained in the wreckage of Ewen’s plane.

After the gravely injured Ewen was taken away and air force officers gathered at the crash site orders were given that what remained of the machine was to be burnt. And so it was.

“The ‘plane was dragged away forthwith, and soon a match ended all possible hope of ever finding out what caused the accident.” (Labor Daily 12 May 1927, p1)

Why did the Air Force want the wrecked machine so quickly destroyed without a proper examination of what was left?

Clearly the Air Force wanted the matter to stay within Air Force control and not be subjected to a police or civilian investigation. Their grip on control however was loosening with every crash. Getting rid of this latest evidence was a quick way of deflecting blame and in modern day language indicate, “nothing to see here.”

Political leaders had questions, a concerned public had questions and bereaved families would certainly have questions. The Opening of Parliament was an historic day and to have the celebrations marred by a shocking Air Force crash caused immense disquiet all-round. Newspapers started demanding answers on behalf of the public. People wanted to know what was going wrong with their Air Force.

The Daily Examiner reported that there:

“ … is a general demand being expressed for an open inquiry into every aspect of the Royal Australian Air Force administration, personnel, equipment and training.” (Daily Examiner, 12 May 1927, p5.)

The Labor Daily called for a Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Commonwealth Air Force. In a blunt statement it said:

“The day has passed when flight should be regarded as a gamble as to whether a man would come down alive or not. Yet that is what the Royal Australian Air Force is rapidly becoming. The service is frankly described here as a ‘suicide club’.” (Labor Daily, 12 May 1927, p1)

While witnesses in Australia said that Ewen couldn’t articulate words after the crash, in New Zealand the ‘Ashburton Guardian’ reported that Air Force authorities were aware of the cause.

“Before he died Ewen said the machine was caught in an air pocket or wind slide. He couldn’t free himself and use the parachute as he was busy trying to flatten out and secure the machine’s position as it fell 1500 feet.” (NZ Ashburton Guardian, 12 May 1927)

This seems a lot of articulated words for a semi-conscious and gravely injured man to put together. In any case, an air pocket or “wind-shear” as it is known today is quite recoverable from 1,000 ft. Also, the other aircraft in Ewen’s formation didn’t experience that phenomenon.

A Private Air Force Inquiry

On the afternoon of the crash a private Air Force Inquiry began and was expected to last for three days. Squadron Leader Drummond led the inquiry and members included Squadron Leader Delarne and Flying Officer Knox-Knight.

A day later in an official statement the Commandant of the Air Force Camp, Squadron Leader Hepburn said:

“The crashed machine was piloted from Point Cook by Sergeant Carroll. He was forced to land at Cootamundra last Monday week, damaging one wheel and a wing. The damage was repaired, and the machine was flown to Canberra four days later.

Flying Officer Ewen flew the machine in formation on Monday without trouble, and had been flying for an hour yesterday before the crash. The machine had been passed by the mechanical branch as airworthy.

After the crash Flight Lieut. Wackett, brother of Wing Commander Wackett, as officer in charge of Point Cook workshops, made an examination and found the controls in perfect working order. The engine switches were on.

The fall was clearly seen by me from the review ground. The machine’s behaviour was like that of a machine in war, the pilot of which had been shot. It glided out of formation and the glide quickly developed into a nose dive.

A parachute was strapped to the pilot ready for use. Any competent airman, if a machine got into a dive at 1000 feet, could do any manoeuvre twice and regain normal flying position.

If the machine were out of control he would have plenty of time to use his parachute; I can say nothing about the cause of the accident, pending the finding of the board, and from what I saw I must regard it as a mystery, except on the hypothesis that the pilot suddenly became indisposed.” (Herald, 10 May 1927, p5)

Hepburn’s statement raises questions such as:

- How could Flight-Lieut. Wackett tell that the controls were in perfect working order as he declared after examining the wreckage, when eye witnesses said that the engine was broken in half and “… merely a ball of twisted metal”?

- How could Wackett tell that there wasn’t a defect with the engine if the engine was mangled?

- Was Flight Lieut. Wackett’s opinion unquestionable because he was Wing Commander Wackett’s brother? Could this reflect a conflict of interest?

- Did Squadron Leader Hepburn doubt Flying Officer Ewen’s competence as a pilot by claiming that a competent airman could bring a plane back to a normal flying position from a nose dive at 1000 feet? Ewen was a competent pilot according to RAAF documentation so the implication is that something went wrong with Ewen. But what?

The Melbourne Air Crash Three Weeks Earlier

A terrible portent appeared in Melbourne’s ‘Labor Call’ on the Thursday before the crash:

“Trouble: Already one of the air fleet from Point Cook to crowd the air at Canberra has met trouble. In making a landing at Cootamundra the tyre of one of the planes burst and the machine did a head-over-heels with the result that the pilot was injured, but the winged authorities refused to disclose his name. It is sincerely to be hoped that there will be no catastrophes at Canberra like that on the day of the Duke’s arrival in Melbourne.” (Labor Call, 5 May 1927, p7)

The prescient article referred not only to Ewen’s plane A2-24 crashing in Cootamundra, but to the serious air fatality in Melbourne three weeks before Ewen’s death. Four RAAF airmen involved in a flying manoeuvre to welcome the Royals were killed after the wings of their two seater planes clipped sending them into tail spins.

The Melbourne accident happened at the very moment the Royal couple were being cheered into the grounds of Government House by a massive crowd of onlookers.

“The ‘planes, luckily, missed the dense crowds in their crash to earth.” (Evening News, 9 May 1927, p13)

In the days leading up to the Royal visit and the ‘Opening’ celebrations in Canberra, RAAF planes had been out doing daily manoeuvres to the delight of Canberra locals. While these manoeuvres were a delight to watch in the air the landing manoeuvres were not so delightful at the aerodrome. There were several landing accidents which left a number of planes damaged and out of action and pilots slightly injured. Nine planes out of 28 from Melbourne and Sydney were disabled in the few days they were at Canberra.

One plane crashed into a gully near the aerodrome and was “smashed to pieces”. Other planes stripped their undercarriages from bad landings. Another came down on its nose, tearing off the propeller and embedding the engine in the ground. (Advocate, Burnie, 11 May 1927, p5) And another plane landed with so much pace, it bounced in the air and landed upside down. (Advocate, Burnie, 13 May 1927, p5)

The combination of incidents had generated “ugly rumours” and the Melbourne Herald reported nine planes, had been damaged in the accidents and were grounded. (Herald, 10 May 1927, p5)

The Daily Telegraph reported that mishaps involving the planes at Canberra were a “daily occurrence”. (Daily Telegraph, 10 May 1927, p2)

Ewen’s death brought the number of young airmen who had lost their lives to six within a four month period and five within a three week period. There were calls for a public inquiry into the affairs of the RAAF to quell the public uneasiness about the crashes. A newspaper headline asked if a “Hoodoo” followed our Air Force planes.[xv]

Eerily, Ewen was said to have “had a feeling that something was going to happen”, and went around saying goodbye to all his friends in the camp. This account survives in the recollections of William (Bill) Glover, a participant in the military review, according to Libraries ACT.

The Cootamundra Factor

The Air Force admitted that Ewen’s plane was involved in a forced landing at Cootamundra on its way to Canberra. After the aircraft was repaired and thoroughly overhauled it flew to Canberra four days later.

“A squadron of aeroplanes from Point Cook reached Cootamundra today en route to Canberra, where they will participate in the ceremonies at the opening of Parliament. … Seven machines landed in the first batch, and three arrived later. Unfortunately, a tyre on one machine burst as it struck the ground, and the aeroplane turned a complete somersault. The pilot was injured, but his name and the nature of his injuries had not been ascertained at a late hour to-night. The machine was only slightly damaged.” (Advertiser, 3 May 1927, p17)

Sydney’s Sun reported that:

“ … the ‘plane somersaulted, landing upside down. The pilot was uninjured, but the machine was slightly damaged.” (Sun, 2 May 1927, p9)

In the official statement released after Ewen’s crash the pilot of the damaged plane was identified as Sergeant D. M. Carroll. Squadron Leader Hepburn, Commandant of the Air Force Camp at Canberra, said that Carroll:

“ … was forced to land at Cootamundra last Monday week, damaging one wheel and a wing. The damage was repaired, and the machine was flown to Canberra four days later.”

Hepburn failed to say what caused the forced landing. He also didn’t say that the plane flipped over in the course of the forced landing and whether the pilot was injured or not.

A modern day definition of a ‘Forced Landing’ is:

“a landing by an aircraft made under factors outside the pilot’s control, such as failure of engines, systems, components or weather which makes continued flight impossible.” [xviii]

A ‘Hard Landing’ is when an aircraft hits the ground at a greater speed than normal and this can be caused by:

“… weather conditions, mechanical problems, pilot decisions and/or pilot error.” [xix]

Whether a forced landing or a hard landing at Cootamundra, the S.E.5A (A2-24) that Ewen flew to his death, underwent a fast repair and overhaul at the Cootamundra aerodrome. The work most likely supervised and declared airworthy by Flight Lt. Wackett the officer in charge of the Point Cook Workshops. The same man who flew one of the De Havilland 9A’s up from Victoria and the same man who declared Ewen’s accident in Canberra was not due to a defect in the machine.

Another nagging question is whether Ewen, as the Point Cook Adjutant, was meant to fly during the celebrations. Did he replace the ‘injured’ pilot Sergeant D. M. Carroll?[xx] Ewen didn’t fly to Canberra. His NAA record states that he “Proc. to Canberra by Train 1/5/27. RO 57/27.” [xxi]

Keeping Air Crashes Out of the News Headlines

Air crashes do make for sensational headlines and the RAAF in the two year period between 1926 and 1927 certainly had its fair share. Ewen’s crash was the final indignity. The crashes became a public relations disaster for the new military arm forcing them to devise a strategy to manage the press and keep air crashes out of the news headlines.

It started with RAAF authorities issuing pilots a directive that they were not to give any details of any accidents to the press, no matter how minor. And it didn’t stop there. A notice appeared in the Victoria Police Gazette forbidding constables from informing newspapers about air accidents as well, a move designed to stop news reporters getting to the scene before Air Force investigators. (C.D. Coulthard-Clark, 1991)

Funeral for a Fallen Airman

Within two days of his death on Wednesday 11 May 1927, Flying Officer Ewen was buried with full military honours. The cortege left Canberra Hospital at 10am and followed roads that two days previously were crowded with an excited public.

Making its way across Lennox Crossing from the hospital, passing Corkhill along what is now King Edward Terrace, it turned right into Scott’s Crossing before reaching the Church cemetery grounds via the western entrance. All the time being escorted by two RAAF planes.

One of the planes flew low and dropped a wreath into the cemetery with a message: “From his dearest friend in New Zealand.” Maybe this friend was the love of his life.

Ewen’s mother residing in New Zealand, agreed to his burial in St John’s Canberra because of his RMC and RAAF connections as well as it being close to the crash site.

One of the most touching and evocative descriptions of his funeral appeared in the Hobart Mercury:

“The remains of Flying Officer Francis Charles Ewen were interred in the churchyard of St. John the Baptist this morning. Under a sombre sky, the sad procession came slowly toward the ancient church along roads still gaily decorated from the festival of Monday. It was a grim irony of fate that brought about his tragic death in, the midst of the celebrations, and it gave the preacher’s words, “In the midst of life we are in death,” a poignant meaning.

First came a party of Air Force men, then a firing party with reversed arms, the carriage, draped with the Union Jack, the dead officer’s sword and flying cap on the coffin, and parties representing, the navy, the army, and the boy scouts. Following the coffin were representatives of the Duke of York, the Governor-General, the Commonwealth, and the Federal Capital Commission. The cold wind brought to the little group waiting at the church fitful passages of Handel’s majestic “Dead March from Saul,” and overhead the Air Force escort circled slowly.

The Bishop of Goulburn, assisted by Canon Ward, both military chaplains, conducted the brief service, and as the Firing party paid its last tribute, and the “Last Post,” with its two notes that seem to say ” gone home,” was sounded, two civil airplanes came down so close that they seemed to skim the church spire, and dropped wreaths on the grave. The other wreaths included one from the New Zealand Government – Flying Officer, Ewen was a New Zealander, one modelled in the shape of an airplane from the Air Force, and the other from the army sisters, who nursed him in his last hours.

Near Flying Officer Ewen’s grave is the historic tombstone with its message of faith and hope …

“For here we have no continuing city, but we seek one to come.” “(Mercury, 12 May 1927, p7)

Air Force to be Probed

Ewen’s crash put the Air Force and its growing fatality list well and truly in the spotlight. However, in the immediate aftermath, Defence Minister Sir William Glasgow and members of the Air Board remained tight lipped about how they would address the issue. The official cloak of secrecy was lowered creating a sense of unease and distrust amongst concerned citizens.

RAAF authorities refused to release information about the accident, including Ewen’s condition and gagged hospital officials from providing updates on their patient.

Soon after the accident photographers were told to “clear out” from the accident scene when they tried photographing the plane wreck just as they were told when trying to get pictures of damaged machines at the aerodrome in the preceding days. (Daily Telegraph, 12 May 1927, p13)

The code of silence only made matters worse for RAAF officialdom as news reporters were forced further afield in their search for a good story. This led to comparisons being made between RAAF landings and civil aviation landings over the same few days in Canberra. It didn’t look good for the RAAF. Civil aviators had made 40 to 50 landings without mishap at the same aerodrome and a further six at the Ainslie air field. The RAAF had daily mishaps.

The better safety record in civil aviation was brandished around in newspaper reports and discussions.[xxii] The six deaths occurring in civil aviation since it began operating in Australia were a small fraction of the military flying fatalities considering the number of flights and mileage covered by the civil airlines. (Worker, 25 May 1927, p13)

Air Force authorities, however, would hear nothing of this comparison saying civil aviators didn’t have to do complicated manoeuvres like Air Force pilots. This reasoning was given short shrift as most of the Air Force accidents had happened in the normal course of flying and landing.

Public confidence in Australian aviation was probably at its lowest with the RAAF seen as a dangerous place to work and watch. Who would want their son, brother or father working in an environment with such a bad safety record? Future recruitment to the service was under threat unless the RAAF was seen to clean up its act.

Inquiry Announced to Regain the Public’s Trust – But Did It?

The Government really had nowhere to go except down an inquiry path to regain the public’s trust in the Air Force. Sir William Glasgow announced a departmental inquiry on 12 May 1927 to fully investigate the whole matter – the number of accidents, number of men killed and injured, cost of damage and pilots’ flying hours – to ascertain whether a fuller, Cabinet endorsed, investigation was necessary. (The Telegraph, 12 May 1927, p5). What the Defence Minister announced was a departmental investigation to determine if there should be an investigation.

Air Board Chief, Group Captain Williams MC AFC., said the RAAF had nothing to hide, and welcomed the fullest inquiry. (Daily Advertiser, Wagga Wagga, 14 May 1927, p4) What else could he say?

The proposed departmental inquiry was ridiculed. Before it even started it was seen as a “white-wash”. Negative headlines ruled the day.

People wanted an exhaustive public inquiry not one held behind closed doors.

The Daily Telegraph said:

“The Defence authorities naturally do not like criticism, but they are going the right way to get it. In fact so sceptical as to the safety of our Air Force machines have the public become that nothing short of a thorough and open inquiry will satisfy them.

If the Defence authorities are so confident that the planes are efficient, why do they not invite such an inquiry and settle the question to the satisfaction of everybody.” (Daily Telegraph, 12 May 1927, p4)

Melbourne’s ‘Herald’ said:

“Nobody ever anticipated the long list of crashes and fatalities and the general feeling is that something is wrong somewhere that needs rectification.

What that something is, the lay mind cannot fathom and the authorities refuse to admit.

How many minor crashes there have been recently only the official files can reveal, and their contents are jealously guarded from the public gaze. Our Air Force is a silent Air Force.”(The Herald, 12 May 1927, p4)

“Discovering the Discovered – Futility of Secret Probes” said the Melbourne Herald as it continued with its criticism of the Air Force in a scathing article about the hypocrisy of the Air Force investigating themselves.

The Herald then revealed the inane recommendations of the inquiry conducted by Group Captain Williams, Squadron Leader Brown, and Squadron Leader L. J. Wackett[xxiii] into the fatal accidents involving Flying Officer W.A. Hotham and Cadet T. B. G Watson in July 1926. Twenty-five witnesses gave evidence to this inquiry which lasted three weeks.

The recommendations made to reduce aeroplane accidents were described by the Herald as “Useless Suggestions”. They included:

- Provision of aeroplanes that cannot be stalled.

- Provision of aero engine power that will not fail.

- Provision of aircraft structures that will not fail, or of multi-engined aircraft.

- Thorough workmanship and inspection in manufacture, overhaul, and repair of engine and aircraft before going into service.

- Thorough inspection and attention to details of maintenance of aircraft in service.

- Thorough training of pilots.

- Proper ground organisation.

- Provision of parachutes for flying personnel.

- Ensuring that persons selected for training as pilots are thoroughly fit for flying duties medically, and that they are periodically examined.

- Discontinuance of training of persons found temperamentally unfit for flying.

The Herald rightly pointed out that there was, “ … not one recommendation which could not have been made before the inquiry was held”, and that the first three recommendations, “ … had no practical application whatever.” And this was because:

- There was yet to be an aeroplane invented which cannot be stalled.

- There was no aero engine power available at the time that would not fail.

- There were no aircraft structures available at the time that would not fail.

“All the inquiry discovered was that if it is impossible for accidents to happen, then accidents will not happen! Surely an extraordinary result from three weeks’ labors (sic).” (Herald, Melbourne, 16 May 1927, p5)

The public wanted to know what was wrong with their Air Force. According to the Herald, they wanted to know why there were so many accidents in Australia if the RAAF had the same principal equipment as other air forces. They also wanted to know how the accidents occurred to decide whether:

“things are being done which ought not to have been done, and whether things are being left undone which ought to be done.” (Herald, Melbourne, 16 May 1927, p5)

In its final pitch the Herald pleads:

“In fact, it wants a public inquiry, so that it can know, not what yet remains to be discovered before air accidents are impossible, but the simple truth about the Royal Australian Air Force.” (Herald, Melbourne, 16 May 1927, p5)

Apart from being ‘bleeding obvious’, the recommendations made by the 1926 inquiry are interesting when looking at Ewen’s accident nearly one year later. The parachute recommendation had been implemented because it was noted Ewen was wearing one and the question was asked by authorities why didn’t he jump and release his parachute? Also, Air Force authorities were very keen not to blame the aircraft or any mechanical defects, including the mechanical workmanship for the accident. Doing so would reflect badly on the efficiency of implementing the recommendations of that 1926 inquiry.

‘The Truth’

On 22 May 1927 the ‘The Truth’[xvi] newspaper in Brisbane published troubling information from Air Force sources who believed that the string of accidents were due to “ … unsuitable machines and incompletely trained men.” Pilots also were not confident and believed every time they went up there was a good chance of crashing down and either dying or being severely injured.

One of the men who was to fly in the Canberra ceremony apparently ran around the mess rooms before departing looking for someone to sign his will. Another pilot took the time to farewell “all and sundry” on the Point Cook base. Both believed that their next meeting “might be at the other end of eternity.”

Ewen was frequently heard saying that he often didn’t know where he was in the air, and everyone on the station knew that he had no ‘air sense’ and was not a good pilot. Neither was young Dix the pilot killed at Point Cook, after his third crash, a few months earlier.

‘The Truth’ report went on to say that the S.E.’s were difficult to fly and described them as “ancient and dangerous … ” and “ … should be sent to the scrap heap.” (Truth ‘Brisbane’, 22 May 1927, p12)

Another Air Force Plane Crashes During Return Flight from Canberra Celebrations

The Air Force, the Government and a concerned public didn’t have long to wait before another crash. Sergeant Ormond Denny after hitting stormy weather was forced to land his S.E.5A on tree tops in wild country near Wangaratta on his way back to Point Cook from the Canberra ceremonies on Tuesday 10 May. He was lucky to escape with only minor injuries but faced a 25 mile (40 km) trek searching for help and was missing for three days.

Exhausted, hungry, and injured he managed to find a farm house and from there he was taken to the nearest railway station. While Denny was missing the RAAF remained silent about their comrade and for all the public knew they made no attempt to find and rescue him. The RAAF also prevented the publication of any information about the incident. (Daily Standard, 13 May 1927, p5)

When he arrived in Melbourne by train from Wangaratta he was met by reporters and said: “I am sorry, but I cannot tell you anything about it.” Asked if he could talk about his experiences after the crash he replied: “I am sorry but I can tell you nothing at all,” as he “nervously hobbled towards the exit.” (Daily Standard, 13 May 1927, p5)

Denny later said that when he was 1000 feet about the mountains his engine failed owing to loss of oil pressure. He said: “I cannot account for the engine trouble. I was flying for three hours on Tuesday and the engine ran well.” (Sun, Sydney, 13 May 1927, p11) Maybe Ewen struck similar trouble.

Prime Minister Bruce Orders Investigation

Whether the Prime Minister Mr Bruce knew about the latest crash is unclear but he was “gravely concerned” about the number of air fatalities and eager to ease the public mind. He announced an independent committee with the tasks of investigating the probable causes of accidents and suggesting ways of preventing them in both the Air Force and Civil aviation.

Calls for a Royal Commission into Aviation Administration Rejected

Mr Bruce announced on Friday the 13th, that the Government had no intention of appointing a Royal Commission to inquire into aviation administration, he instead proposed a permanent body with five committee members: a technical expert not connected to the department or aviation interests as Chairman; a representative each from the Air Force and Civil aviation with flying and technical experience; an inspector of aircraft construction and an officer from the Defence Research Laboratory.[xxiv]

Air Accidents Investigation Committee (AAIC)

Members of the Air Accidents Investigation Committee (AAIC) as it was called, included: Professor H. Payne, Dean of the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Melbourne (chairman); Squadron Leader E. Harrison, (RAAF); Captain E. J. Jones, Superintendent of Flying Operations (Civil Aviation Branch); Mr. M. Bell, Superintendent of Defence Laboratories; and Lieut.-Colonel H. B. L. Gipps, Chief Inspector of Munitions (Inspection Branch). (Mercury, 17 May 1927, p8)

The Prime Minister said there would be no secrecy except when it came to matters of defence. Very convenient. As all members of the committee were Defence people except the Chairman, accusations abounded before investigations even began, that it was hardly independent or unbiased.

Captain Geoffrey Hughes MC., AFC., President of the Australian Aero Club said he could no longer remain silent about the Federal Government appointing a departmental board instead of establishing a full and independent inquiry.

“Everyone knows that there may be the odd accident that cannot be explained, but no man of wide experience in these matters will believe that a succession of accidents, such as have been reported in the last years do not indicate a weak link somewhere.”

He reminded people of the results of an inquiry into Air Force smashes tabled in Parliament in August 1926 which he said, was:

“… a complete vindication of the methods and organisation of the Air Force and with due solemnity attributed all accidents to the everlasting ‘error of judgement by the pilot’. What do you expect when the Board was composed solely of senior officers of the Air Force itself.” (Evening News, 18 May 1927, p1)

This was the very path Air Force authorities were taking immediately after Ewen’s plane crashed. Trying to blame Ewen.

Negative headlines kept rolling out after the investigations began:

- “Star Chamber Methods. Inquiry into RAAF is Kept Secret.” (Tweed Daily, 1 June 1927, p2)

- “Hush Tactics of Air Force to Operate at Inquiry.” (Daily Telegraph, 1 June 1927, p3)

The investigations took exactly four months to complete and on 26 October 1927 the report was released to the press. That is, those elements of the report that were made public. (Age, 27 Oct 1927, p12)

Back in September the Defence Minister told Mr Charlton, Leader of the Opposition, that:

“Except where it is considered undesirable in the public interest to do so, the reports of the Air Accidents Investigation Committee will be made public.” (Daily Telegraph, 29 Sept 1927, p2)

The ‘public’ report was brief and was included in its entirety in Hansard by Sir Neville Howse in reply to a Question on Notice from the Opposition Leader.[xxv]

Not surprisingly, some would say, the findings into Ewen’s crash were really no different to the initial Coroner’s report – machine airworthy, impossible to determine cause. The report said:

“In connection with the review of troops at Canberra by His Royal Highness the Duke of York at the opening of Parliament, a single-seat fighter was seen to leave the formation immediately after the formation had made a left-hand turn.

The machine took up a steep gliding position with a slight turning movement, and this glide was continued until it struck the ground at a point opposite to and some 600 yards away from the front of Parliament House. The machine was badly smashed, and, although the pilot was conscious, he was too seriously injured to make a statement as to what had occurred, and died that same evening.

The evidence brought to light that the machine was airworthy prior to flight, and, as far as it was possible to ascertain from the wreckage, there was no failure of any part of the machine during flight. No evidence was obtainable as to whether or not the controls had been jammed or their function interfered with through any object carried in the machine. There was no evidence that the pilot was other than medically fit.

It was impossible to determine the cause of the accident.” [xxvi]

So that was it. Hardly an adequate explanation.[xxvii]

The AAIC concluded that Denny’s accident was caused by the engine seizing, “… owing to exhaustion of the supply of lubricating oil.” [xxviii]

There was no need to quickly dispose of this wreckage because it couldn’t be found – not even by experienced bushmen.[xxix] (The Age, 20 May 1927, p11) In fact, the Air Force personnel sent out to look for the wrecked plane became lost themselves before it was finally located.

Reading between the lines, recommendations did emerge guised as Government initiatives.

On 20 October 1927 new regulations governing the investigation of air accidents came into effect with the AAIC being made a permanent body. Comprising a Chairman, who would be suitably remunerated, and four members, it would have extensive powers to investigate air accidents referred to it by the Minister and make recommendations to prevent a recurrence. The Committee was given rights to call witnesses and gain access to aircraft establishments to examine equipment and processes.

But, most importantly:

“Any forced landing or accident, or serious structural damage, or injury to any person, whether in aircraft or not, must be reported to the Comptroller of Civil Aviation. Where such an accident occurs in any Federal Territory and involves injury to any passenger, the aircraft or the remains of it shall not be removed until three days have elapsed after notification.” (Telegraph, Brisbane, 20 Oct 1927, p5)

In other words there would be no more quick disposal of plane wreckages as happened with Ewen’s SE5A (A2-A4) on 9 May 1927.

There were other revelations in the Federal Budget handed down in late September by Treasurer, Dr Earle Page. Provision was made for improved Air Force accommodation at Point Cook and Laverton in Victoria and Richmond in NSW. And it was revealed that steps would be taken to purchase additional new aircraft for the RAAF. [xxx] Maybe these budgetary measures were a result of information that came to light, but not made public, during the inquiry into air accidents.

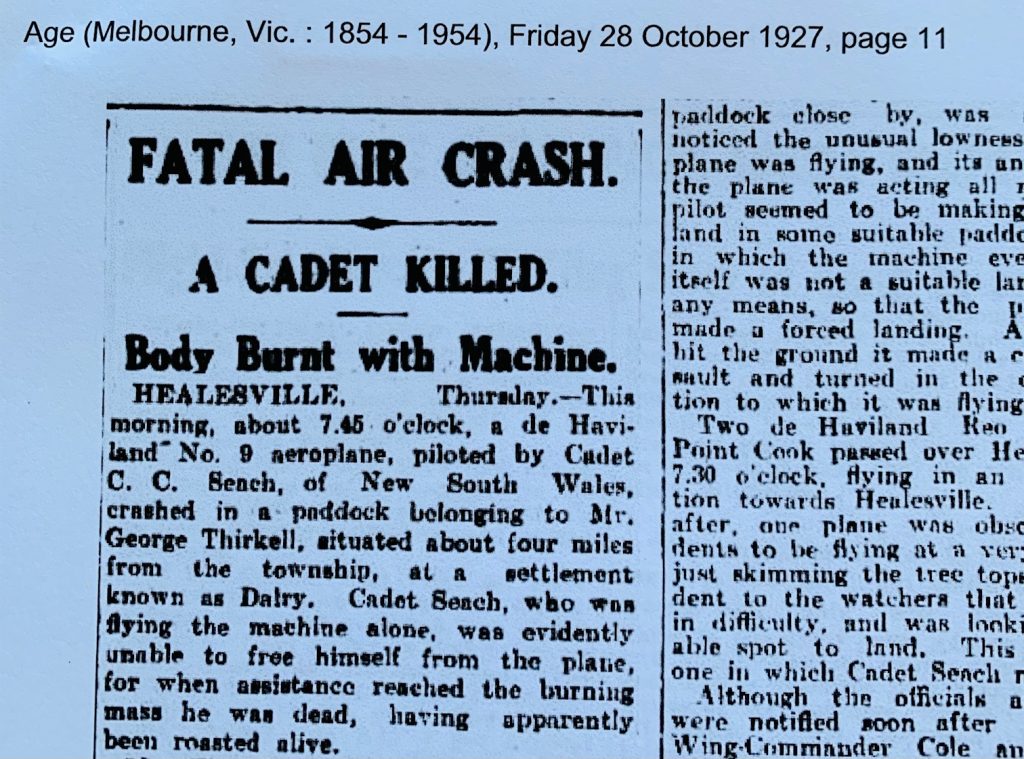

Another Crash Another Fatality

Within days of the AAIC report being released to the press, a young Point Cook Air Cadet, Clarence Seach aged 24 years, was incinerated when the plane he was flying nosedived to the ground from 200 feet in the air and burst into flames. The crash occurred five miles from Healesville.

More work for the AAIC and more questions for the Defence Minister. Mr Blakely (Labor, NSW) asked whether the Minister would consider the question of altering the method of training at Point Cook and investigate the type of machines used.

Sir Neville Howse representing the Minister for Defence said it was still not known what caused the accident adding:

“A Court of Inquiry had been convened by the Air Board and the AAIC was also inquiring. The pilot had done 86 hours of flying, 42 dual and 44 solo, and had flown 22 hours in this type of machine.” (Geelong Advertiser, 29 Oct 1927, p2)

At least Air Cadet Seach’s flying hours were released to the public unlike Flying Officer Ewen’s which didn’t appear to be publicly disclosed.

Mr Blakely kept pressing the Defence Minister with questions and the Minister finally revealed the findings of a court of inquiry[xxxi] which found that:

“… in no case had the evidence indicated that flying accidents in the R.A.A.F. had been due to machines, equipment or training.” (Herald, 2 Nov 1927, p5).

By deduction that leaves only pilots to blame.

The Minister also said that:

“The government was satisfied that the present system of training which was exactly the same as that adopted in the Royal Air Force (RAF), was the most thorough and efficient yet developed in any part of the world.” (The Advertiser, 3 Nov 1927, p13)

Despite this ringing endorsement, the Minister added:

“Arrangements had been made for the loan of an officer of the RAF for duty as Director of Training at RAAF Headquarters and he was en route to Australia.” (The Advertiser, 3 Nov 1927, p13)

It was a disastrous period for the RAAF in those fledgling days with the spate of horrific accidents. For those in charge it must have been distressing, if not embarrassing. Arguing that the fatalities were not excessive in comparison to other British Empire countries ,[xxxii] didn’t mean much when the accidents kept happening in quick succession. It was a public relations nightmare not only with Australian civilians but within the defence forces. As the infant arm of Australia’s military services the RAAF was still in the process of justifying its existence.

We must not forget that when the RAAF was instituted in 1921, it was only 17 years since the Wright brothers successfully flew the first motorised plane – for 52 seconds – on 17 December 1903. So the aeronautical industry was still young and flying was an adventurous career for young men who probably looked to the WW1 aces for their inspiration.

Excuses, however, were no comfort for the pilots who lost their lives, for their loved ones and for the general public. There was something wrong in those days and the RAAF would have been better placed to face up to rather than cover up possible weaknesses in occupational health and safety, flight training and the application of mechanical knowledge.

A Modern Theory on What Caused Ewen’s S.E.5.A – A2-24 to Crash? – Carbon Monoxide

The question of what caused Ewen to suddenly lose control of his plane is still pondered by aviators and historians today. The crash was never fully explained by RAAF officials and investigators in 1927 and questions linger. There did seem to be a cover-up. The fact that the machine was disposed of means that no theory can be tested and proved beyond reasonable doubt. Experts today do not believe that the flip over accident in Cootamundra caused an aerodynamic fault severe enough to cause the crash in Canberra. This was reasonably tested given that the plane flew safely on to Canberra and was then flown around Canberra in the days leading up to the opening celebrations.

Ewen was trained to bring his plane out of a dive, so what stopped him doing that? The proposition that he suddenly became indisposed as Squadron Leader Hepburn suggested seems plausible and reasonable. But why and how?

The theory is that Ewen ‘swooned’ and lost control like some pilots did in the Great War. If he swooned or fainted it meant that he lost consciousness through the loss of oxygen to his brain. How could this happen?

One strong possibility is Carbon Monoxide poisoning from an exhaust leak. This is where the integrity of Ewen’s machine A2-24 comes into question and the Cootamundra accident. A crack in the exhaust pipe, initiated during the flip-over and getting worse with vibration, is not out of the question. This caused a mysterious crash near Sydney a few years ago.

The critical question is: Why wasn’t this considered in 1927?

RAAF’s Last Words on Ewen

The final words on Ewen’s service record written on an angle in red ink:

“Killed in Aeroplane

accident at Canberra 9.5.27”[xxxiii]

And that was it. No explanation for why he was flying that day. It was just an ordinary day in the eyes of the military recorders.

This young pilot has a special place in the history of our Federal Parliament and should always be remembered for his sacrifice on that fateful day.

Acknowledgements

Thank you Tony Maple for your additional research and support. Thank you also for your inspiration after an impromptu walk in the St John’s Church graveyard where you pointed out Flying Officer Francis Ewen’s final resting place. Thank you to James Oglethorpe from 3 Squadron RAAF Association for setting me straight on a number of technical matters associated with planes and flying in the early days of aviation and providing crucial knowledge to enhance the story. Accordingly, the story was updated on 7 December 2021.

Thank you also to the Canberra and Region Heritage Researchers (CRHR) group for the awakening to look no further than the history of our own region for compelling stories.

Sources

Trove www.trove.nla.gov.au

Coulthard-Clark C.D (Christopher David) & Australia. Royal Australian Air Force, (issuing body) (1991), The Third Brother. The Royal Australian Air Force 1921-39. Allen & Unwin in association with the Royal Australian Air Force, North Sydney, NSW. p316-317

The Duntroon Society Newsletter 1/2020, ‘Duntroon, Aeroplanes and Accidents’, April 2020.

Daley, Paul (2012), Canberra, NewSouth, University of New South Wales Press Ltd, Sydney, NSW., Australia.

National Archives of Australia: https://www.naa.gov.au/

3 Squadron, RAAF Association

Endnotes

[i] Ewen died aged 27 years and 10 months.

[ii] NAA: A9300, Ewen F C, 5371598

[iii] NAA: A9300, Ewen F C, 5371598

[iv] Definition: “Adjutant general, an army or air force official, originally the chief assistant or staff officer to a general in command but later a senior staff officer with solely administrative responsibilities.” (www.britannica.com)

[v] NAA: A9300, Ewen F C, 5371598

[vi] The’ Imperial Gift’ to Australia comprised the following aircraft:

- 35 × Avro 504K trainers

- 35 × Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a fighters

- 30 × Airco/de Haviland DH-9a bombers

- 28 × Airco/de Haviland DH-9 bombers

[vii] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fGNSQrMYRKM (Pilot says in this video that while the SE5A is a “peach to fly” it’s a “little monkey to land” and explains why 12:24/24:44)

[viii] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cK6k0zNxSgA

[ix] Rottenbury Hill was east of Parliament House not in front. Corkhill was the mound/small hill in front of Parliament House and most likely site of crash.

[x] https://www.nfsa.gov.au/collection/curated/opening-canberra-australias-capital-city ‘The Opening of Canberra, Australia’s Capital City. NFSA ID: 43907, 1927

[xi] Within the bounds of the Corkhill family property

[xii] https://www.3squadron.org.au/subpages/Parliament_Opening_Air%20Crash_1927.htm

[xiii] Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 – 1954), Tuesday 10 May 1927, page 5 and Coulthard-Clark (1991) p316-317

[xiv] NSW, Australia, Registers of Coroners’ Inquests, 1821-1937. Sourced through Ancestry.com.au by Tony Maple

[xv] Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 – 1931), Monday 9 May 1927, page 13

[xvi] While ‘The Truth’ was a scandal sheet and sensationalist in its reporting, it broke some of the most important stories around the country including: Agent Orange and Vietnam Veterans, Maralinga and effects of the A-Bomb testing and the Melbourne-Voyager collision. The paper, in which ever State it was published, was renowned for highlighting personal scandals but most importantly exposing social injustices.

[xvii] https://www.nfsa.gov.au/collection/curated/opening-canberra-australias-capital-city ‘The Opening of Canberra, Australia’s Capital City. NFSA ID: 43907, 1927

[xviii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forced_landing

[xix] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hard_landing

[xx] One report said Carroll was “injured” and another said he was “not injured”

[xxi] NAA: A9300, Ewen F C, 5371598

[xxii] Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954), Monday 16 May 1927, page 8

[xxiii] Both Squadron Leaders involved in this 1926 inquiry were Wing Commanders by May 1927.

[xxiv] The members announced a few days later included: Professor H. Payne, Dean of the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Melbourne (chairman); Squadron Leader E. Harrison, (RAAF); Captain E. J. Jones, Superintendent of Flying Operations (Civil Aviation Branch); Mr. M. Bell, Superintendent of Defence Laboratories; and Lieut.-Colonel H. B. L. Gipps, Chief Inspector of Munitions (Inspection Branch). (Mercury, 17 May 1927, p8)

[xxvi] Hansard, House of Representatives 15 November 1927, ‘Air Accidents Investigation Committee’, page 1387

[xxvii] Paul Daley in his book ‘Canberra’ said: “The accident, never adequately explained, … ” p.215

[xxviii] https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;adv=yes;orderBy=customrank;page=0;query=air%20accidents%20investigation%20committee%20Content%3A%22air%20force%22%20Date%3A01%2F05%2F1927%20%3E%3E%2031%2F12%2F1927%20Dataset%3Ahansardr,hansardr80,hansardrIndex;rec=0;resCount=Default

[xxix] Denny’s plane was eventually found in the ranges near Tolmie in June 1927. Parts of the plane were found entangled in trees but the engine was believed to be “still intact”. Members of the Air Force had been out searching for the missing plane for some time and in a touch of irony three members of the search party became lost and spent a freezing cold night in the Tolmie hills without food.

[xxx] https://historichansard.net/hofreps/1927/19270928_reps_10_116/#subdebate-52-0-s0

[xxxi] A Court of Inquiry consisted of flying officers who followed every serious accident.

[xxxii] Defence Minister in Parliament as reported by ‘The Advertiser’, 3 November 1927, p13

[xxxiii] NAA: A9300, Ewen F C, 5371598

Hi, this was a fascinating article, thank you! Are you able to include a footnote to confirm if the exact crash location was revealed and how to find it?

Hi Bill

So sorry for not updating. If you live in Canberra we believe the crash happened at the beginning (the National Library end) of Reconciliation Place on the northwestern corner of the Questacon grounds. The site was revealed on a National Trust (ACT) Heritage Walk. We calculated that the YWCA tent was erected on what is now the Questacon carpark and the plane came down 50-60 yards beyond the tent and on the opposite side of the hill from where the gun salute took place (so the southern side of Corkhill). Corkhill of course isn’t there anymore. I will update in the next day or two. Thanks so much for your interest,

Regards

Sue