John and Susannah HETHERTON: County Tyrone to Healesville

Their Voyage and Pioneering Life in Rural Victoria, Australia 1840 to 1887

John HETHERTON (1819-1887) & Susannah HARPER (1819-1885)

County Tyrone – Healesville

Foreword

Writing about John and Susannah HETHERTON was so rewarding. At age 22 years they rejected a life of poverty, said goodbye to Ireland and their families and emigrated to Australia. Full of hope and possibility, they seized the opportunity to create a better life for themselves and their family. Their courage and strength of character should be honoured. They started life in Australia with nothing, but a few metal cups, plates and utensils taken from the ship.

Intrepid pioneers facing enormous challenges, they carved a life in the rural areas of Victoria. They were part of the first communities in the Merriang district, Healesville and Gobur. Their lives did not make headlines or become immortalised in monuments or history books. Through hard work, resilience and family devotion they made a significant contribution to the foundation of Australian society and its collective spirit.

We will never know everything about their lives and relationships but we do know they left a legacy through their descendants. There is an invisible thread connecting us to John and Susannah and that’s something we should all be proud of.

I never knew about the HETHERTONS until Lorna Jeffrey contacted me through Ancestry.com. The HETHERTON name was never mentioned in any family discussions about our ancestors. Elizabeth CHANDLER’S maiden name was a mystery to my mother, Dawn McNISH (HOLLAND). I know she would be thrilled if she was alive today to learn about her great grandmother’s parents. I also love that she named me Susan Elizabeth after my 1xG and 2xG Grandmothers Susan and Elizabeth.

We are fortunate these days to have widespread access to online records and information which makes family history research easier and less costly than it did in the past. However, not all questions can be answered. Irish records particularly can be problematic because most historical information is available only at the Parish level and some records have been destroyed completely.

I suspect that the original HETHERTON and the HARPER families came from England or Scotland during the Plantation of Ulster period in the early 1600’s. A turbulent period when the British confiscated land belonging to Irish landholders and populated it with British Protestants from England, Scotland and Wales. But that is research for another day.

Thank you to Lorna JEFFERY for sharing so much information, being so inspirational and for organising the 2017 HETHERTON family reunion. Thanks also to Roger HEEPS for always answering my emails and sharing his knowledge. There are gaps in the story and I would be very grateful if those gaps could be filled. I’ve listed all my sources and I sincerely hope I haven’t misrepresented or misquoted any person, author or organisation. If I have, I apologise unreservedly.

Please contact me if you have any additional information, stories or corrections that I can add to the John and Susannah story. I’d love to hear from you.

Susan

September 19, 2017

Introduction

John HETHERTON and Susannah HARPER were only 22 when they sailed from Plymouth harbour on 16 May 1841 with their toddler son Robert. They were bounty immigrants aboard the barque, Strathfieldsaye. After three and a half months at sea, they landed in Geelong harbour, Port Phillip, on 30 August 1841.

I tell the story of their emigration and pioneering life in Australia using documentary evidence where possible. This includes the ship’s list, electoral rolls, census records, and birth and death records. The tale has pitfalls because not all the facts about their life are recorded or available. I portray their lives in the social and historical context of the period and make assumptions about how they were affected by the circumstances of the day. I used newspaper reports from the 1840’s onward, government reports, historical studies, and academic studies. Family history research and stories of the assisted emigration system and the early colonial days were also used.

John and Susannah could read but not write[i] so early personal diaries, letters or notes do not exist. They weren’t famous or infamous. They didn’t make headlines. They were decent, hard-working people. People who took personal risks to secure independence, dignity and financial security for themselves, their family and for generations to come. Like other early pioneer workers, they helped build a nation. Their story is one of courage, hardship and determination, it starts in Ireland.

Birthplace

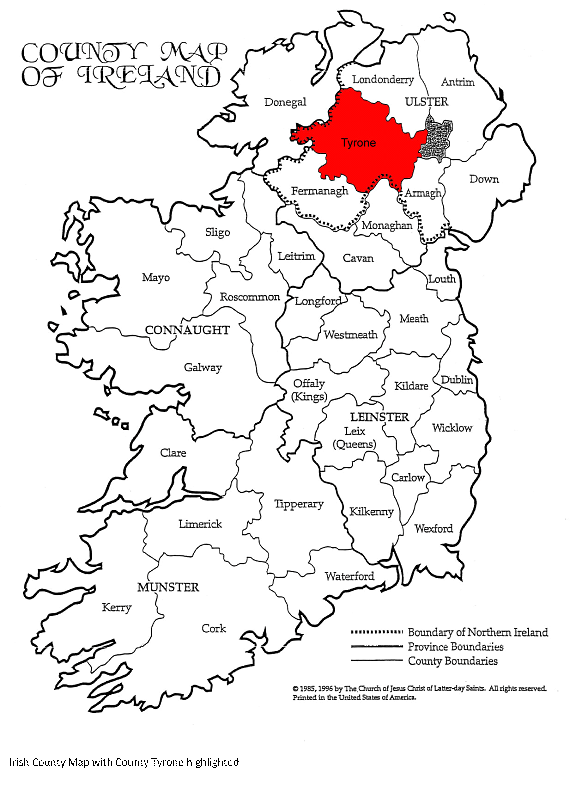

John and Susannah came from County Tyrone, Northern Ireland[ii]. The ship’s records indicate they were both born in 1819, married as teenagers and were no older than 20 years when they became parents to Robert.

John and Susannah came from County Tyrone, Northern Ireland[ii]. The ship’s records indicate they were both born in 1819, married as teenagers and were no older than 20 years when they became parents to Robert.

I have not found records of their births or when their marriage took place even though that information was a requirement for boarding and disembarking the Strathfieldsaye. Their decision to emigrate to Australia was probably influenced by a compelling desire to escape inevitable poverty and a life with little or no future in Ireland.

Parents

To date, John’s parents remain a mystery. They are not named or referred to on any official document or record. His death certificate states they are ‘Unknown’. On the other hand, Susannah’s parents, John HARPER and Susannah ROSS, were named on her death certificate by son John. I wonder why the family knew their mother’s parents and not their father’s?

John and Susannah’s birthplace is also a mystery. The Griffiths Valuation (GV)[iii] of County Tyrone may provide clues even though it was undertaken in 1860, 19 years after the couple emigrated. Within the Clonfeacle Parish in the Barony of Middle Dungannon, there are several Townlands where HARPERS are listed. Either one or all could be related to Susannah – or none!

Something however, stands out; a John and Samuel HARPER leased an equally divided 21-acre plot in the same  Townland of Kilnacart as a James HEATHERTON who had a house with no land or garden valued at 5 shillings. James HEATHERTON appears to have been a labourer for Joseph WHORR, a tenant farmer leasing a neighbouring farm of 49 acres from the same landlord, Sir James Matthew STRONGE Baronet (BT), as John and Samuel HARPER.

Townland of Kilnacart as a James HEATHERTON who had a house with no land or garden valued at 5 shillings. James HEATHERTON appears to have been a labourer for Joseph WHORR, a tenant farmer leasing a neighbouring farm of 49 acres from the same landlord, Sir James Matthew STRONGE Baronet (BT), as John and Samuel HARPER.

While James surname HEATHERTON is a variation of the HETHERTON, it was the same spelling used in Susannah’s Death Notice in 1885.[iv] “HETHERTON” however, was used on her Death Certificate. Other variations to the name include Hetherington, Heatherington, Hitherton, Hatherton and even Hetherston. These inconsistencies show up throughout the research on notices and documents, such as the Strathfieldsaye’s List of Passengers, baptismal, marriage and death certificates, and even the 1856 Electoral Roll.

For romantics like me, it seems too much of a coincidence that a HEATHERTON and a HARPER family were close neighbours in the same Parish and Townland and worked the same lands owned by Sir James Matthew STRONGE Bt. We also know it was common for relationships and marriages to occur within the same or neighbouring parishes and townlands. Poorer classes couldn’t afford to travel long distances for courtships.

For rationalists however, none of John and Susannah’s sons were called James. Old Irish naming conventions have the first son being named after the father’s father. Therefore, John’s father’s name was likely Robert HETHERTON.

The GV names a Robert HETHERTON in the County of Longford, leasing 23 acres from the Rev. John Grey PORTER in the Parish of Columbkille. [v] Maybe this is John’s father. The distance between Longford and the middle of County Tyrone is about 75 miles, a long way to travel in the mid 1800’s – but not impossible for a young male looking for work.

Whatever the truth; somehow, somewhere and at some time John and Susannah fell in love, married and went on to have a large family and live a tough, enterprising and industrious life on the other side of the world.

Ireland in the Late 1830’s and Early 1840’s

Life was harsh in the years before the young couple emigrated. The Irish economy was in a state of economic transition. For the lower classes it was a time of economic despair and disruption. Mechanisation in the linen industry and the introduction of modern farming methods in agriculture was a looming catastrophe for the small tenant farmer, the agricultural labourer and their families.

County Tyrone

County Tyrone was particularly hard hit by the economic upheaval. If John and Susannah lived in the Eastern half of the county or the so called ‘Linen Triangle’ – the region around Armagh, Lisburn and Dunganoon – their families were vulnerable.

Although we may never identify the ‘real’ HETHERTON and HARPER families belonging to Susannah and John, we can confidently predict they were from the lower classes of Tyrone society. Susannah’s death certificate describes her father, John HARPER as a “Labourer”[vi]. If they were from the agricultural sector they would have been very exposed to the prevailing economic times.

As the lowest class of workers, cottiers or labourers usually received a small cabin and a plot of land from the larger farmers. Their rents were usually high – up to five pounds a year for less than an acre to cultivate. From this meagre acreage, usually on the poorest of soils, the labourer was expected to make a living and feed and clothe his family. There was little prospect for economic improvement and they were at the mercy of their landlord.

Labouring Class

The Census Commissioners of 1841 described labourers’ homes as “4th class housing” and this housing made up nearly one-third of all residences in County Tyrone.

“Living conditions were abysmal and often shared with animals. A typical cabin was a mere mud hovel unfit for the residence of human beings, built on the worst part of the farms, and consisting mostly of but one smoky apartment, without window or chimney.”

Their saving grace was the supplemental income from spinning and weaving which helped pay their rent. Most small farmers had one or two looms in the house and loom income often exceeded the income made from the land.[vii]

When times were good and weaving prospered sub-division between father and son was a viable and regular practice. However, the arrival of mechanisation, ‘wet spinning’ and large-scale factory production forced the collapse of the home textile industry. Farmers were left with high rents and land too small to make a living. In the Clonfeacle parish, over 50% of farms were less than 10 acres like John and Samuel Harper’s.

To make matters worse, while the economy was declining landowners pushed on with new and more efficient farming methods to raise productivity and income. They also shortened leases and began consolidating small uneconomic farms. The traditional practices of common land sharing and subdivision on estates managed by small tenant farmers were also stopped.

The shortening of the land leases can be traced back 100 years earlier to 1740 when Edward Harper, maybe an ancestor of Susannah, had his lease of 105 acres in the Parish of Clonfeacle shortened to “3 Lives” by Lord Powerscourt.[viii]

Throughout the County these new measures caused social and economic distress for small farmers and agricultural workers. Not only did tensions grow between these classes and the landowners, but divisions grew within and between members of the lower classes. Former farmers were being forced into labouring and therefore competing for scarce work with agricultural labourers.

Curran wrote:

“Labourers had been by far the poorest sector of the agricultural workforce, now they had to contend with the class above them – small tenant farmers dropping into their stratum. Naturally with an economic recession affecting all layers of the social makeup of the community, less work became available and this coupled with a massive increase in the number of labourers ensured a wretched existence for this class of people.”

Division between classes and within classes was one thing but a more traumatic division for someone to face was division within the family unit and this was increasingly tested during bad economic times. Land occupancy was the main issue that pitted one family member against the other, especially as land holdings were getting smaller the more they were divided. It meant siblings being left out or disinherited with no future in sight. Maybe this was John’s situation and migration provided an opportunity to escape a miserable future in Ireland.

Bounty Immigrants Bound for Australia

The HETHERTONS came to Australia as bounty immigrants – an assisted immigration system introduced by Governor Bourke in October 1835 with the following set of regulations:

“The Persons accepted should be mechanics, tradesmen, or agricultural labourers;

They should have references as to their character from responsible persons such as the local magistrate or clergyman; and

To prove their age they should have certificate of Baptism.”[ix]

The major goal of the system, funded by the sale of land, was to rebalance the make-up of the population.

Earlier assisted passage schemes were set up to relieve a social crisis in Britain by sending out poor male workers. However, it led to a disproportionate number of single males to females in the Colony. In 1838 men outnumbered women by a ratio of four to one (4:1) in the city. In rural areas however, the ratio was a staggering twenty to one (20:1). This made women vulnerable to abuse and sexual exploitation, especially those from poorer classes, both Aboriginal and European.

To help overcome this problem the government increased the intake of young married couples and single women. Also, the expanding wealthier classes were calling out for more domestic help and manual labourers as the economy grew. John and Susannah fitted the bill perfectly, they were young and married and John was a “Labourer” and Susannah a “Domestic Servant”.

The Bounty Scheme went through several changes. By 1841 when the HETHERTONS emigrated the Colonial Government had started contracting local agents to deliver suitable immigrants to the Colony. The colonial agents then employed agents in the UK to source or advertise for immigrants and to also engage and contract a ship.

The Strathfieldsaye passenger list in August 1841 was headed by the following statement:

“List of immigrants (British Subjects) who have been introduced into the Colony of NSW, under the regulations of March 3rd 1840 by Mr John Marshall of London, through the agency of Messrs Thomas Enscoe and James of Port Phillip in pursuance of the authority conveyed to these Gentlemen in the letter of the Colonial Secretary dated 29th May 1840, and who arrived at Port Phillip in the ship ‘Strathfieldsaye’ Captain (George Warren) under the Medical Superintendence of Dr (Thomas Baynton) on the 30th day of August 1841.”

The Surgeon Superintendent or doctor had one of the most important jobs on the bounty ships. He was responsible for keeping the emigrants as fit and healthy as possible to safeguard the anticipated bounty payment. John and Susannah attracted a bounty of 19 pounds each – the standard payment in 1840 and for Robert the bounty was 5 pounds.

London agents used advertisements like the one below to attract potential emigrants to Australia:

“AUSTRALIAN PACKET SHIPS

TO

PORT PHILIP & SYDNEY

______

Persons intending to proceed to Australia, are

respectfully informed that Ships are despatched from

London and Plymouth, for the above ports, every month

throughout the year, on fixed days, with strict punctuality.

They are all of the first class, and of large tonnage; have

poops, and the best possible accommodations; carry

experienced Surgeons; and are liberally fitted and supplied

with every essential to the comfort of Cabin, Intermediate’

and Steerage Passengers.

A FREE PASSAGE will be granted by these fine Vessels

to suitable Married Agricultural Labourers and Mechanics,

and also to Single Females, if in accordance with the

Colonial Regulations.

The demand for Labour in the Colony is EXTENSIVELY

URGENT, and every competent and well-conducted Person

may reckon, with certainty, on immediate and constant

employment, at liberal wages.

All particulars may be known on application (post

paid) to Mr. JOHN MARSHALL, Australian Emigration

Agent, 26, Birchin Lane, Cornhill, London; or to his

Agent, Mr. May, Bookseller, Taunton.”[x]

If they met the requirements, applicants were then required to fill out application forms. If you could read but not write like Susannah and John, you probably received assistance completing the form.

Some of the mandatory information required included: names and ages of all family members emigrating, their birthplace and date of birth, whether an individual had suffered smallpox or been vaccinated against smallpox, whether an applicant could read or write; current trade and length of current employment, name of employer, name of Parish minister, whether married (and if so a marriage certificate to be provided) and whether you were in debt. Applicants were warned that if Inspectors found any information to be false, or if an individual was found to have an infectious disease or be in a poor state of health, they would be refused permission to board the Ship.

Once applications were approved considerable planning and preparation was involved. It was also costly. Emigrants were told they would be provided with items for use during the voyage which they could keep afterwards such as cooking utensils, bedding, cutlery, metal plates and mugs – useful basics for their new life ahead. Clothing however, was the sole responsibility of the emigrant with minimum requirements essential for the voyage.

“15. The Emigrants must bring their own Clothing, which will be inspected at the Port by an Officer of the Commissioners; and they will not be allowed to embark unless they have a sufficient stock for the voyage, not less, for each Person, than –

FOR MALES

Six Shirts

Six pairs Stockings

Two ditto Shoes

Two complete suits of exterior Clothing

FOR FEMALES

Six Shifts

Two Flannel Petticoats

Six Pairs Stockings

Two ditto Shoes

Two Gowns

With Sheets, Towels and Soap. But the larger the stock of Clothing the better for health and comfort during the voyage, which usually lasts about four months, and as the Emigrants have always to pass through very hot and very cold weather, they should be prepared for both; 2 or 3 Serge Shirts for Men, and Flannel for Women and Children, are strongly recommended.”

Tools of trade could be included but overall baggage for each adult could weigh no more than half a ton or be bigger than a 10-cubic foot box.

Good-byes were final. The excitement and prospect of a new life thousands of miles away were tempered by the sadness of leaving loved ones behind forever. If you couldn’t write like Susannah, John and their respective families, communication across the seas would be impossible.

Getting to Port

Travelling to a port of departure was a big exercise and probably expensive. Several stages were necessary for the HETHERTONS. As Tyrone is an inland county and in the heart of Northern Ireland the first stage was getting to an Irish port. The second stage was catching a vessel across the Irish Sea to England and the final stage, getting to Plymouth. All stages challenging journeys in themselves, especially with a toddler in tow.

Their families and Parish probably helped in financial and practical ways to assemble and prepare their sailing ‘kit’. London agent, John Marshall, most likely helped with travel expenses to ensure they arrived at Plymouth harbour in time for the compulsory ‘orientation’ to ship life and pre-voyage checks.

Florence Chuk writes:

“The journey to the point of embarkation was an adventure in itself to untravelled agricultural workers. Many emigration agents advertised free travel to the port as part of their inducement to emigrate, and parishes often paid a few pence per mile to assist a parishioner on his way.”

We can only speculate on the route they took from their hometown in County Tyrone. With limited means of road transport in 1840 Ireland the HETHERTONS probably travelled by a Bianconi car, the equivalent of Australia’s Cobb and Co. An adventure but an uncomfortable one on rough dirt roads.[xi]

Crossing the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea leg was not always plain sailing either and depending on the weather could be unpredictable and dangerous. A witness gave a bleak description of the crossing to an 1854 British Parliamentary Select Committee Inquiry.

Q: “Were you ever in a gale of wind?”

A: “I cannot say that I was but I have had the unhappiness to come from Cork – this is going across to England – with a large body of immigrants, many of whom had to be put in hospital after arrival. And one man of the name of Ryan from Nenagh in the county of Tipperary, the father of seven children, died an hour after he landed from cramps produced by the wetting and fatigue he passed through during the night.”

Q: “How many might there have been upon that occasion on the deck?”

A: “I think the numbers were about 140.” [On a boat about the size of a current Manly ferry according to Perry.]

Q: “No shelter?”

A: “Not the slightest.”

Q: “What length was the run?”

A: “30-odd hours.”

Q: “What year was that?”

A: “1840.”

Q: “Fifteen years ago?”

A: “Yes. That occurrence terminated my connection with the bounty immigration from the port of Plymouth.”

Q: “Do such things occur now?”

A: “I cannot answer that. All I am prepared to state or prove is that there is no shelter or protection given to Irish immigrants proceeding to English ports.”

Q: “You have heard the evidence of the last witness with reference to the deck passengers, does your own experience bear that out?”

A: “Yes, entirely. I have gone to Liverpool expressly to wait the arrival of Irish steamers, and no language in my command can describe the scenes I have witnessed there. The people were positively prostrated and scarcely able to walk after they got out of the steamers. And then they were seized hold of by unprincipled runners so well known in Liverpool. In fact, I consider the manner in which passengers are conveyed from Irish to English ports, disgraceful, dangerous and inhumane.”

Q: “Was that because they were just off a voyage and seasick or merely because they had been on an upper deck exposed to the weather?”

A: “Prostrated from the inclemency of the weather.”

Q: “And the cold?”

A: “Yes.”

Q: “And wet through or anything of that sort?”

A: “As wet as if they had been dipped in the sea.”

Q: “But the great majority of the passengers shipped in a vessel for a passage from Ireland to England who had never been at sea before would be seasick all the way?”

A: “Yes, and if you add to that the wetting I described, they would be in a most helpless state.”

Q: “Do you think not the greater part of that would probably be from seasickness?”

A: “Seasickness must always leave a very debilitated feeling for a long time, and that must be greatly increased by the suffering from cold at night.”[xii]

While comparatively short the Irish Sea crossing may have been the worst part of the entire journey especially for emigrants with children, like John and Susannah. There was also a general whisper during the 1840’s and 1850’s, “that any couple setting out from Britain with two children under five could expect one to die at sea” – a terrible warning, that must have sent shivers of dread through the minds of young parents contemplating emigration to Australia.

Plymouth Emigrants’ Depot

After crossing the dangerous Irish Sea emigrants were required to stay in accommodation at the docklands before departure. They were housed for a few days in cramped and generally unhealthy conditions while being checked medically and issued with their ‘mess kits’ for sailing. Liverpool had a notorious reputation for housing emigrants and in 1853:

“(they)continued to be exposed to infection at an emotional, perhaps traumatic, time of their lives, before being packed into cramped, unfamiliar quarters which encouraged the rapid germination and spread of any disease. In 1854 three Australian vessels put back into Liverpool with cholera on board. Many others sailed on in spite of illness with tragic consequences.”

Plymouth’s accommodation, in 1840 according to Chuk:

“… was little better than that of Liverpool. In September the death of an emigrant was reported in the local newspaper: an Irish emigrant, waiting with others for a passage to Australia, fell from the doorway of the upper floor of a loft.”

“In July 1849 cholera spread through the dockland area of Plymouth. Cesspools, piled-up filth, and appalling privies between dwellings exacerbated the problem. The Navy made efforts to cover the worst of the refuse with newly burned lime, but could do little about the drains. A report stated that ‘Sewers, when any exist, are in a very bad state … Heads, entrails of fish, putrid vegetables clogged the drains in a stinking mess, while pigs kept in backyards added to the foul smell. One of the worst areas was within fifteen yards of a ward of the Naval Hospital’.”

John and Susannah travelled in 1841, 8 years before this report and conditions then were probably similar if not worse.

They were also sailing before the 1842 Passengers Act which surpassed the previous Passengers Acts of the British Parliament in terms of the protection it gave passengers, agents and ship masters.

“Based on past errors and mismanagement, it laid down rules for every possible exigency at sea. Strict guidelines also specified the construction of the vessels, modifications for passenger use, space needed per passenger, and amount and quality of rations.”

They were protected to some degree by regulations implemented on 3 March 1840 following the Report of the Immigration Committee of 1839. Here, ship owners were subject to strict requirements before receiving any bounty. These conditions included certificates covering the character of emigrants and also that provisions and accommodation during the voyage complied with the Passengers Act. In addition, the Government could withhold the payment of gratuities to the ship’s surgeon and officers if there was evidence of misconduct or negligence in their duties. The system however, was still open to abuse.

Life Aboard the Strathfieldsaye

Despite the limited safeguards and the uncertainty ahead it was probably with relief and optimism that a healthy John, Susannah and little Robert finally boarded the Strathfieldsaye with their fellow passengers. They included: 225 bounty emigrants; Master of the Ship, George Warren; Surgeon Superintendent, Dr Thomas Baynton[xiii]; the crew – a 1st, 2nd and 3rd mate; 27 unassisted passengers; 15 convicts, 5 policemen, a bull and a cow. The HETHERTONS were Family Number 21.[xiv]

Their accommodation in the lower decks or steerage class was cramped with only 6 ‘4” or 193cms of headroom. There was a dining table stretching down the centre of the ship with double storey bunks either side – each 3 ft or 91 cms wide. Susannah and John shared the equivalent of a single bed today.[xv]

In steerage class, whole families were allocated single bed sized accommodation. Photo taken at the Dunbrody Famine Ship display.

The Health of Emigrants a Major Priority

The ship’s doctor as mentioned earlier had the important task of maintaining good hygiene and nutrition standards. Disease and infection spreading in the confined conditions was the biggest risk. Prior to the Bounty Scheme, many deaths occurred on ships due to Scarlet Fever, Typhus and Cholera – an important reason for ensuring that only healthy emigrants boarded ships.

No system is perfect and no matter how strict the medical checks, there was no guarantee that individuals incubating disease did not embark. After the Bounty Scheme and despite supposedly stricter regulations for emigrant ships the infamous Ticonderoga had a disastrous voyage in 1852.

The double-decker ship carrying 795 passengers became a ‘fever-ship’ with tragic consequences – 168 passengers and 2 crew members died of Typhus on the ill-fated voyage from Liverpool.[xvi] A memorial to the people who died on board the ship or in quarantine was unveiled as recently as 10 November 2002 on the site of the old Quarantine Station at Point Nepean, Portsea.[xvii]

Personal Hygiene

Personal hygiene was an issue for females as many women wouldn’t bathe during the entire journey due to lack of privacy. Men could make do with a saltwater dip on the upper deck. Shipboard rules and routines kept decks, floors, toilets, bunks and tables scrubbed and cleaned frequently. Bedding was shaken and aired twice weekly and stored away daily. Washing was allowed twice a week on deck. There were also rules about shipboard behaviour in relation to alcohol, smoking, gambling and fighting.

Mealtimes and Food

At meal times emigrants were usually grouped with others from the same neighbourhoods, church or parish. This probably encouraged friendships and useful support networks to form. Susannah and John may have been put with the MCMAHON’S, Family number 27 and the only other family from County Tyrone. James and Maria were travelling with their three children, Robert (5 years), John (4 years) and Corlina (10 months). Twelve young unmarried men and women were also from County Tyrone.

Meals were shared and made from rations including: meat, preserved meat, bread, flour, suet, rice, peas, sugar, vinegar, tinned bouillon, biscuits and raisins. Water was kept in “well-charred casks” but passengers were advised on some voyages to “bring jam and things to mix with the water when it gets stale.” In addition, the ship carried so called ‘medical comforts’. These included: arrowroot, sugar, scotch barley, port wine, stout, rum and lemon juice that was given out regularly by the ships’ doctor to prevent scurvy.

A Successful Voyage

There isn’t much written about the Strathfieldsaye and her May-August 1841 voyage probably because it was relatively incident free. Florence Chuk describes the sea journey:

“… as pleasant and the 288 immigrants enjoyed good health throughout the voyage, expressing themselves completely satisfied with their treatment. There were no deaths on board, and only one birth, that of a baby girl. At Geelong, all documents of baptism and character were found to be in order.”

It was either sheer luck or good fortune that there were no deaths on this 1841 voyage, given the young and inexperienced Dr Baynton who at 22 years, the same age as Susannah and John, had just qualified as a medical practitioner after being apprenticed to his father.[xviii]

On other voyages, there were horrendous stories of accidents and mishaps, unfavourable weather and tumultuous seas, death and disease, malnourishment and filthy conditions. Like today they were the stories that attracted the news headlines. Nevertheless, John, Susannah and Robert were very fortunate to arrive safely in Port Phillip with their health intact.

Arriving at Geelong Harbour, Port Phillip

Emigrants on the Strathfieldsaye were lucky that the new 1840 regulations prevented shippers from discharging passengers immediately upon arrival. Immediate disembarkation had previously caused serious problems for young single women especially. Shippers were now required to provide emigrants with suitable accommodation on shore or allow them to remain on the ship for up to ten days. They were also required to provide emigrants with the same rations they’d received during the voyage.[xix] These regulations gave the HETHERTONS and fellow passengers time to acclimatise to their new surroundings before their pioneering lives began.

Finding Employment

In terms of employment, agents were under no obligation to find work for the migrants they imported or care about their well-being. A ship’s arrival was announced in the newspapers of the day and it was met by employers looking for the best workers.

“The Surgeon of the Ship and the Immigration Agent (at Melbourne) supervised the residents who came either to the ship or the Immigration Depot seeking employees. If an immigrant refused a reasonable offer, the authorities turned them out of the immigrant depot and they had to fend for themselves.”[xx]

When Susannah and John arrived in August 1841 they were greeted by high unemployment and a shortage of accommodation. Migrant ships were arriving weekly in 1841 and the tightening labour market was partly due to the large number of emigrants now preferring Australia over America as their destination. In addition, the ‘speculative’ land and property boom in Melbourne was losing traction, and there was a depression in England affecting wool and livestock prices. These factors had flow-on effects throughout the colony eventually sending it into a financial depression in 1842-43.

Pioneering Life Begins in the Agricultural Area of Merriang (including Kinlochewe and Donnybrook)

It appears that John was offered a job in the agricultural shire of Merriang[xxi] about 20 miles north of Melbourne. The family settled in the parish of Kalkallo or more specifically Kinlochewe. Although there are no records of John’s first employer there was plenty of work available in these rural outskirts. The earliest records of his occupation are the 1844 and 1845 baptismal certificates of daughters Elizabeth and Sarah Jane where he is described as a ‘Labourer’ and then a ‘Farm Servant’.

Naming nightmares and area confusion

The re-naming of geographic locations muddies the waters for researchers and the Merriang area is a clear example. Rocky Water Holes became Donnybrook which then became Kalkallo. Donnybrook has been described as two miles north of Kinlochewe which was previously Morang which was previously Mernda, and one and a half miles east of Kalkallo. A part of Donnybrook, perhaps the old settlement of Merriang, was renamed Beveridge and although the railway station was in Beveridge it was still called Donnybrook Station!

Kinlochewe

How did ‘Kinlochewe’ fit into this geographic puzzle, the place where John and Susannah first settled and where four of their children were born? One document suggests Kinlochewe covered a large area and others suggest it was just the extent of the village.

Kinlochewe became the first settlement in the Parish of Kalkallo springing up in defiance of the 1840 Parish Survey which had earmarked a section of land to be reserved for a township and a small settlement called Rocky Water Holes (present-day Donnybrook). The village was established downstream of the reserve where there was a natural ford on Merri Creek. This was the only way travellers could get to the Sydney Road and later to the northern goldfields.

A small community of tenant farmers also developed about a mile east of the ford on the properties of Thomas Walker’s ‘Banchor Farm’ and William McKenzie’s ‘Kinlochewe Estate’ and this too became known as Kinlochewe. It became a thriving area of 400 residents living in dwellings described as: “being a slab hut with a bark roof and an earthen floor.” [xxii]

In the early years as suggested by Elizabeth’s and Sarah Jane’s Baptismal records, John most likely worked for one of the large property owners as an agricultural labourer or farm servant. He may have graduated to a tenant farmer after that. Certainly, by 1856, he had pulled together enough money to own freehold property in the Merriang Shire.[xxiii]

To add to the confusion and ‘mystery’ of Kinlochewe the Victorian Heritage Council in a document on Mt Ridley Station states:

“In the Crown Land Sales of April 1840, the land on the hill, then known as Kinlochewe, 640 acres of Section 12 of the Parish of Kalkallo, was purchased for £1312 (41/- an acre) by Duncan Cameron.”

Even more confusion when reading the Craigieburn Historical Interest Group (GHIG) website which states:

“The geographical region once known as ‘Kinlochewe’ covered a relatively large area. It ran approximately from the Merri Creek at the township of Kinlochewe in the east, out as far as Donnybrook and Kalkallo in the north, across to the Deep Creek in the west and as far as Somerton in the south.”

The CHIG site also says that today’s Craigieburn was once known as Kinlochewe.

It seems that settlers either lived in the Kinlochewe township that had spontaneously developed next to the Merri creek ford (now Summerhill Road) or they lived on tenant farms. The 1990 City of Whittlesea Heritage Study says:

“Kinlochewe began as a village reserve centred around a natural ford in the Merri Creek. The Kinlochewe inn opened in 1841 followed by a blacksmith John Kent and wheelwright William Kirkpatrick. Those who farmed at Kinlochewe included William and Daniel McKenzie, Robert Campbell, Alexander and Josiah Harrison, Alexander and Godfrey McDonald, James Malcolm, Thomas Walker, Andrew Munson, McCrae Moritz, William Hartley Budd, Captain James Pearson and Dr Thomas Wilson.”

Thomas Combe Esq described a beautiful area:

“I came upon Kinlochewe and gazed on an open and magnificent county, hill and valley alternating in fanciful and grotesque irregularity. My eye wandered over this richly diversified country with great delight resting at last on the deep blue mountain ranges that everywhere abounded the horizon.”

Another reference in a National Trust article refers to: “the mysterious 1840’s Scottish tenant farming settlement of Kinlochewe.” The site in the northern area of Merri Creek is now part of an archaeological precinct. John Batman had two sheep stations on the Merri Creek at Kinlochewe and ran the largest flock of sheep in the first period of settlement. Writing about the Batman outstations in Kinlochewe, David Moloney said:

“The surrounding red gum woodland plains are integral to the northern site. They are a surprisingly intact representation of Melbourne’s original landscape and clearly illustrate the rationale of the (Batman’s) outstation.”

The woodland pastures were often described as “just like a gentleman’s park and a delight to gallop through”.

It is largely an unknown era and there are concerns about the area’s heritage going unrecognised. A concerned Moloney wrote in 2010:

“The heritage of the Merri Creek area and early farming era, including the ruins of stone buildings and possibly unique dry stone ‘cultivation’ paddocks, remains little known or explored. There is a threat that these areas will be engulfed by urban growth plans.”

Family Life

Back to the HETHERTON family. John and Susannah’s second baby and first Australian born child, Elizabeth arrived on 28 May 1843 at Kinlochewe, or Morang NSW[xxiv] as stated on her birth registration. She was baptised nearly a year later on 12 May 1844 and on that certificate, John was described as a Labourer. Like most babies in that era she was probably born at home with the help of the district midwife. Three more children were also born in Kinlochewe, Sarah Jane on 3 August 1845, Susannah on 11 October 1848 and John in 1849. John and Sarah unfortunately died in 1850. The three children who followed were all born in Donnybrook, John in 1852, Henry in 1857 and Isobella Jane in 1859.

Seeking Medical Help

Kinlochewe didn’t have a doctor until a Dr STEWART took up residence in April 1850, nearly 9 years after the HETHERTONS arrival. His residency was announced in ‘The Argus’ on 1 April of that year:

“A medical gentleman (Dr Stewart) has taken up his abode here, and doubtless he will be a welcome resident in the neighbourhood, for in the absence of medical aid both poor and rich are not only inconvenienced but frequently great sufferers upon a road subject to many casualties. We believe he is of Scotch origin and good connections and reports speak well of his abilities. We wish him every success.”

The arrival of Dr STEWART probably couldn’t have come fast enough for the Kinlochewe residents. But for the HETHERTONS, even his presence didn’t prevent the deaths of Sarah Jane, aged 5 years and John aged 1 year, in October 1850. The children died days apart John on October 21 and Sarah Jane on October 26. A time of heartbreak and deep sorrow for the family.

A Time of Grief

Poor Susannah and John (who was then described as a farmer on the death certificates) had to endure two burials within 5 days of each other. Describing the burial of her 4-year-old nephew in the early 1850’s, a Scottish immigrant, Jane McCracken, wrote: “The funeral represented ‘the laying of earth of the First of a Race in a New Country, the land of their adoption. An act of History in a Family, the consecrating of a sacred spot, that indissolvable (sic) link of connection to that soil.’” [xxv] By burying their babies in their adopted land Susannah and John’s connection to Australia was now irrevocable.

We can only speculate on what caused John and Sarah Jane’s deaths. 1850 was a year of exceptionally hot and dry weather.[xxvi] This may have compromised the local water supply and created conditions where dysentery or other diarrhoeal diseases put the family at risk, especially the younger ones. Dysentery was the biggest killer of babies and young children at the time.

However, the first outbreak of measles occurred in Victoria in 1850, brought in on the ship ‘Persian’ from England. [xxvii] There was also a report from Geelong in ‘The Argus’ on 5 October 1850 that said: “There is no news stirring, the town is very quiet and dull, and many people suffering from the influenza.” Whatever caused their deaths whether it was dysentery, diarrhoea, diphtheria, measles or influenza, it is highly likely they died from the same contagious disease.

Old Folk Remedies

Mothers, like Susannah generally played family doctor in the pioneering days where folk remedies from ‘back home’ played an important role. They faced epidemics of influenza, measles, whooping cough, scarlet fever, diphtheria, and dysentery as well as infections like bronchitis and pneumonia, not to mention injuries from accidents and the general aches and pains associated with hard physical labour.

Medicine cabinets were filled with concoctions for aches and pains usually made from methylated spirits, camphorated oil, and vinegar. One liniment consisted of a mixture of ½ pint vinegar and turpentine, 2 egg whites and 4 cakes of camphor which was usually stored in a corked bottle. A mixture of methylated spirits and camphorated oil for hot, sore and aching feet made by Lily HOLLAND in the 1960’s may have been a recipe handed down from the HETHERTON/CHANDLER women.

Many home remedies were created for; drawing pus from infected wounds and boils, bruises, bronchitis, pneumonia and pleurisy. These remedies were usually made from whatever was available in the kitchen or garden at the time and usually revolved around hot poultices made from bread, vegetables like carrot, onion and potato, flour, oil and bran.

A mustard plaster was the strongest poultice – a combination of mustard, lard, linseed meal, castor oil or egg white. Ingredients were cooked up, mashed and spread on a cloth and placed carefully on the patient to avoid burning the skin and causing a ‘double injury’. Sore throats were often treated with a mixture of kerosene and eucalyptus oil on a lump of sugar.

A more interesting remedy for infected sores and wounds was made by leaving a covered jar of separated cream in a warm place until it went mouldy. It was then warmed up until the mould settled on the bottom of the saucepan and the remainder poured off into jars and sealed. Apparently, the cream lasted for years. Without knowing maybe our women pioneers made the first antibiotic ointment.[xxviii]

Daily Life for Pioneering Women

For most colonial women, especially the wives and mothers in rural and remote areas, life was one of harsh domesticity with their role probably taken for granted by the household males. They made do with cramped conditions in a one or two-roomed hut with floors of compressed soil, ceilings of unbleached sheeting and walls of lime plaster or wheat bags needing regular whitewashing. There was little or no privacy for parents.

Life was not for the faint-hearted – it was physically tough, ‘back-breaking’ and exhausting. Creature comforts were not available let alone affordable. Susannah’s day would begin after waking on a mattress probably stuffed with; “cocky-chaff, dried grass, fowls’ feathers or gum leaves”. A long list of jobs awaited her: fire stoking, bread making, collecting and boiling water, cooking breakfast, attending to babies and children, milking, churning butter, washing, ironing, tending the kitchen garden and preparing an evening meal. All laborious and exhausting tasks made more taxing during pregnancy or with toddlers underfoot. At night there was always mending, knitting, sewing, crocheting or spinning to do.

These unsung heroines didn’t have time to complain, they had no choice but to take everything in their stride. No wonder Susannah’s death notice in June 1885 said that her “work on earth” was done:

“Heatherton – At Healesville, on the 6th June, after a lingering illness, Susannah the wife of John Heatherton, aged sixty-seven years. Her end was peace.

Farewell to Husband and children dear, My work on earth is done, my sufferings o’er; I hope to dwell with Jesus evermore.”[xxix]

Black Thursday 6 February 1851

The HETHERTONS not only contended with the close deaths of baby John and Sarah Jane in October 1850. Four months later, on 6 February 1851, a devastating fire, the Black Thursday bushfire, descended on the area burning Kinlochewe to the ground. The baptism certificates of the children show there were no more births in Kinlochewe. After 1850 all were born in Donnybrook.

The Black Thursday bushfires ravaged the colony. Sweeping through the northern outskirts of Melbourne around Merriang, the fire avoided the major homesteads of Olrig and Mt Ridley thanks to a change in wind direction. The village of Kinlochewe, home to 400 residents wasn’t so lucky.

People woke to an oppressively hot day with strong gusty winds from the north. By 11 am the temperature had reached 117°F (or 47°C) in the shade. By midday, the wind was gale force; so fierce that it blew thick smoke over Bass Strait ‘where day turned to night’ on the north coast of Tasmania.

The CHIG has information on its website about the bushfire and describes the havoc wreaked on the area.[xxx] The bushfire broke out in the north and west of Melbourne around Sunbury. It gathered force as several small fires converged into a single fire front destroying everything in its path as it swept down Merri and Darebin Creeks and the Plenty River. Melbourne itself was in grave danger as the fire encircled the town.

Twelve people (5 from the same family) were killed and a million sheep and thousands of cattle were lost. The fire left behind:

“blackened homesteads, smouldering forests, charred carcasses of sheep, oxen, horses, poultry and wild animals and the face of the country presented such an aspect of ruin and devastation as could never be effaced from the recollections of those who witnessed and survived the calamity.”

Equipment available to fight a fire of such ferocity was primitive and water scarce due to the prolonged drought. Also, pioneers who had largely come from much wetter and colder climates had little or no experience with bushfires of this magnitude. William Strutt’s famous ‘Black Thursday’ painting depicted the terror of people and animals alike as they raced to escape the inferno.

It took years and thousands of pounds to recover from Black Thursday. Some places never recovered like the village of Kinlochewe. Now considered unprofitable to rebuild because the Sydney Road had become a more reliable northern route. The township disappeared after 1851 – literally raised from the map.

The HETHERTONS may have been one of the families burnt out on Black Thursday and as a result moved further up the road to Donnybrook.[xxxi] There is no record of this. All we know is that by 1852, a year after the fires they are recorded as living in Donnybrook. By 1856 John HETHERTON had become a freehold property owner in the Merriang Shire.[xxxii]

Local Aboriginal Activity

Around the time Susannah and John arrived in the area, Richard Kirby one of the early land holders in Kalkallo noted that: “There were plenty of blacks about, but they were quiet and harmless.”[xxxiii] The HETHERTON family probably witnessed the local indigenous activity with interest and curiosity. Living until she was 95 years, daughter Elizabeth’s obituary in the local Healesville newspaper mentioned her “most retentive memory” and that, “it was most interesting to hear her relate incidents that happened in the early days of the colony when the blacks roamed around.”[xxxiv]

The territory of the Wurundjeri-willam clan,[xxxv] the original inhabitants of the area, ran all the way along the Merri Creek from the Yarra bend to its source in Wallan.[xxxvi] The creek provided plenty of food such as eel, fish and duck and the grasslands plenty of emu and kangaroo.

“Women waded through the Merri with string bags suspended around their neck, searching the bottom of the stream for shellfish. Emu and kangaroo were hunted in the surrounding grasslands. In the forests and hills, possum was a staple source of food and clothing. The flesh of the possum was cooked and eaten, while the skin was saved to be sewn into valuable waterproof cloaks.”[xxxvii]

Five years before the HETHERTONS arrived in the area, Rev. J. R Orton described the traditional life of the Aboriginal people of the Port Phillip district. In an 1836 report to the Wesleyan Missionary Society he said:

“They associate in tribes and are in constant habit of wandering having no houses of any description nor fixed place of abode, though in their wandering they generally confine themselves to certain limits, beyond which they seldom stray.

The only means of screening themselves from the inclemency of the weather is by erecting a sort of breakwind of boughs of trees, under the lee of which they squat or lie down and sleep for the night, and they usually seek for fresh quarters for the ensuing night wherever they may happen to be in the course of their excursions.

The whole tribe seldom wander together but separate into families consisting from ten to twenty persons, to scatter themselves for the purpose of obtaining food. The men hunt and fish for their subsistence. The kangaroo and opossum are the principal objects of their hunting pursuits, which they practice in a singular and artful manner. They usually cover themselves completely with green boughs of trees so as to resemble a bush, then they move gently along so as to be unperceived by the unsuspecting object of their prey, until they are within reach by their spear, which they use with great dexterity and throw to considerable distance with amazing force and precision. Having struck the animal they throw off their disguise, advance and secure their game.

The women, during the hunting excursions of the men, are generally employed gathering succulent roots which are their only substitute to bread and form a principal ingredient of their food.

Their clothing principally consists of a garment of kangaroo or opossum skins sewn together with the fibrous parts of the animal, which they throw over their shoulders and which reaches down to the knees. Their hair is black, coarse and long, usually decorated with kangaroo teeth, claws of animals, bones of fish, pieces of earthenware and buttons from Europeans, or anything of the kind.

Many of them have their faces whimsically painted and have fish and other small bones pierced through the ears, and other small bones on the dividing cartilage of the nose, which are worn as ornamental appendages. (in Cannon (ed) 1982 82-84)”[xxxviii]

Three years later in 1839, Rev. Orton realised that European settlement had changed the traditional Aboriginal way of life forever. Lands that had once been used by Aboriginals for hunting and gathering to Melbourne’s north and west had now largely been taken over by squatters for grazing livestock.

Between 1835 and 1845 several settlements and mission stations including the Merri Creek Aboriginal school were established in the area but then abandoned. The school was poorly attended probably because a standard English curriculum was taught without the inclusion of any traditional Wurrundjeri teachings.

In 1859 a group of Woi Wurrung and Daung Wurrung, tried to settle on land near Yea, (about 40 miles away) to live and farm their own country like white men. It was strongly opposed by European settlers and the Aboriginals were forced to relocate to a new government station, Coranderrk, at Healesville in 1863. Coranderrk eventually became the home to all remaining Woi wurrung and other Port Phillip District Aboriginals.

Most of the Coranderrk settlement was built and maintained by William (Bill) HOLLAND and his father, John HOLLAND.[xxxix] William was the Father-in-law to a HETHERTON descendant, Lily KEARNEY (Elizabeth’s granddaughter), who married Allan HOLLAND in 1922.

Bushrangers

Our early settlers lived in constant fear of being terrorised by bushrangers. In 1842 the area around Merriang, “was in a state of dismay with bushrangers at large.” J. W Payne writes a graphic account of a gang causing trouble along the Merriang Road in April 1842. [xl] We don’t know for sure if John and Susannah were in the area at the time as our earliest record is Elizabeth’s birth in May 1843. If they were, this escapade would have been the talk of the settlement.

Four men, John WILLIAMS (a bounty immigrant), Daniel JEPPS (a sailor), Charles ELLIS (an expired convict) and Martin FORGARTY (a bounty immigrant) headed Merriang’s way, “sticking up and robbing everyone they met.” They were chased by a posse of four constables on horseback from one property to another along the Merriang Road. The gang targeted six properties, PIKE’S station first, followed by HARRISON’S, RIDER’S and then BEAR’S. Mr RIDER ended up joining the pursuit which headed to SHERWIN’S station where the gang stole a watch and a pistol after exchanging shots with the SHERWIN brothers. The pursuit ended at Mr Campbell HUNTER’S hut with a bloody gun battle.

The tale has a gruesome finale. Spectators from neighbouring properties and further afield lured by rumour and the sound of gunfire, gathered near HUNTER’S property to watch events unfold.

The leader of the outlaws, John WILLIAMS became separated from the other three who had barricaded themselves in the hut. WILLIAMS ran to a nearby store house where he was hunted down by constable Oliver GOURLAY. Constable GOURLAY forced his way through the door and was confronted by WILLIAMS holding a gun in each hand. The account goes:

“The man fired the pistol with his right hand, Mr Gourlay dodged his head, avoided the shot, and knocking aside the pistol in the man’s left hand, collared him, pushed a pistol into his mouth and pulled the trigger…… but it missed fire.”

A frantic tussle ensued with more gun fire and pistol butt exchanges between the men until help arrived and WILLIAMS was shot dead. The other three men surrendered and were taken into custody and then to Melbourne. PAYNE writes:

“The narrative continues with the farcical trial when no witnesses for the defence were called, the testimonial dinner to the heroic posse, and the eventual public execution, with the three prisoners seated on their coffins, arriving in a bullock cart, followed by the executioner carrying a sack, later to contain his fee, the clothes of the felons.”!!

The KELLYS

Fast forward to 1854 and the birth in Beveridge of infamous bushranger Ned KELLY. Ned lived in the area for the early part of his childhood until parents John and Ellen moved the family to Avenel in 1860. Ellen’s family, the QUINNS, were established settlers in the area when John Kelly came looking for work at the QUINN farm in the late 1840’s after serving his time in Van Dieman’s Land. He took a fancy to Ellen, the QUINN’S daughter, and married her in St Francis church, Melbourne, despite their age difference and her parents’ lack of consent. There was always local rumour about the QUINNS’ and KELLYS’ involvement in horse and cattle rustling in the area. The HETHERTONS probably knew the families and if not personally certainly by reputation.

Community Life – The Local Pub

The local hotel was integral to community life in colonial days. Apart from the times when local landowners opened their properties for community and sporting events, the pub was the only place where people could gather and socialise for celebrations, dances and for swapping local information. James MALCOLM, one of the wealthy landowners often made Olrig Station available for big community events including fairs, family picnic days, cricket and horse racing.

John may have enjoyed a drink or two at the local Kinlochewe pub situated on the Kinlochewe Estate near the junction of the old and new Sydney Roads. The hotel, a 14-roomed brick and wood property was built in 1841 but the first owners, the MUIRSON brothers, went bankrupt. William BUDD bought the property in 1844 along with its “stabling, fruit garden, 50 acres of arable land, 108 acres of grazing land and six paddocks.”[xli]

The new publican settled in and became not only mine host of the Kinlochewe Inn and Hotel but the principal organiser of horse races between Kinlochewe and Donnybrook. Early horse racing was popular and usually went hand in hand with hoteliers. It was an important community pastime attracting interest from the population at large and was something that all levels of society could participate in and enjoy.

Horse Racing

On 2 February 1847, the Kinlochewe race meeting was held at MALCOLM’S Olrig Station with George LEACH of the Somerton Hotel, judge and Kinlochewe Inn’s William BUDD the treasurer. James MALCOLM and another local landholder, William KIRBY were stewards.

The first and main race of the day was fittingly the ‘Publican’s Purse’- a race of two miles with prize money of 20 sovereigns. Two two-mile races followed and a ‘Hurdle Race’ of five, four-foot-high leaps. Horses were obviously bred to stay. The final races included a ‘Hack Race’ for a “splendid hunting saddle and a double rein bridle” and a ‘Trotting Race’ twice around the course for £10.

Mr BUDD applied to the Licensing Board to erect a tent or booth on the racecourse that day to celebrate Robert BURN’S Birthday. The day was going to be more than just horse racing and by the end one suspects, the ‘Publican’s Purse’ was overflowing. Hopefully John took the family to the races that day where they enjoyed themselves and he backed a winner.

A few years later John had more choice if he wanted a drink as more hotels were built in the area to cope with the large number of passing travellers to the gold fields in northern Victoria.

“Donnybrook, once had no fewer than seventeen hotels. Its main street, Hawkey Street was now part of Sydney Road and there were fifteen other busy streets in the town which in 1850 could handle 150 coaching and travellers’ horses simultaneously.”

The Merriang Hotel

The Merriang Hotel built in 1858 was purchased in 1859 by John CHANDLER who became the licensee. It may well have become John’s hotel of choice as the HETHERTON and CHANDLER families developed what appears to be a close and trusting relationship. The families were joined by matrimony not once, but twice. Elizabeth HETHERTON married William CHANDLER in 1864 and Susan HETHERTON married James in 1870.

Schoolmaster, Stephen Skinner lived at the Merriang Hotel when he first arrived in 1861 until his new cottage was built. His diary provides a colourful account of the frustrations he experienced getting the cottage finished. He refers to a Mr HETHERINGTON, who is most likely our John HETHERTON who seems to able to turn his hand to anything:

“March 11, 1861. Cook, the carpenter, began putting up our cottage, to be finished and ready in a week.

Good Friday. Committee agreed to lay out 2 pound on my house, in canvas and papering, and contribute 1 pound towards 5 pound to move furniture from Melbourne.

Thurs. 4th April. My worthy host Chandler, under pretence of getting canvas and paper, set off about 3 a.m. on Monday and has been on the ‘spree’ ever since at the Rocky Water Holes’, Kalkallo. Consequently, my place remains in a state of nature.

Sat. 6th April. Nothing more done to the cottage though the lining paper etc. are all ready. No doors or windows yet and it will be 8 weeks next Monday since it began and I have lost money and pupils.

Sun. 7th April. Rev. Hollis in afternoon, pretty good attendance.

Tues. 9th April. Mr Hetherington will puddle floor of my place, it will want 2 days to dry.

Tues. 16th. Harvey nearly finished cottage, no door or ceiling. Mr Hetherington promised to put wood work in ceiling (calico very cheap), to whitewash fireplace, to put bark on floor, to help build privy. Door is being made.

Sunday 22nd April. Entered home.”[xlii]

Healesville

Around 1866 the Merriang area started to decline economically and many residents moved away, the HETHERTONS (and CHANDLERS eventually) moved to the newly established township of Healesville, about 40 miles (or 67.5 kilometres) southeast of Donnybrook. According to the Healesville and District Historical Society:

“About 1866 a Mr Hetherton built a cottage beside the Grace Burn River in ‘The Nook’. He selected a site under a mining statute, but his permit was withdrawn and he was not allowed to stay on and purchase the land.” For years, The Nook, which is part of Queens Park, was known as Hetherton’s Reserve. After the cottage was removed the reserve was planted with trees and ferns to create a shady and popular spot for picnics in summer. In the early 1900s a group of local ladies raised funds to enhance Queens Park and erected a fountain in ‘The Nook’ but unfortunately it no longer works. The RSL and the Shire of Healesville placed a plaque at the base dedicated to service men and women who served their country overseas between 1945 and 1973.”[xliii]

The cottage John HETHERTON built was made of bark and it was the second cottage in Healesville. [xliv] A Miner’s Right was taken out by John Harrison in 1886 twenty years after the original cottage was built. This didn’t deter John HETHERTON Jnr (b.1852) from erecting a paling house on the site in 1889. A heritage sign at The Nook says that:

“There was fencing and a garden consisting of fruit trees, grape vines, vegetables and raspberry canes.”

His family were allowed to live there despite the land being reserved for public use in 1890. The house was eventually removed in 1909 to the corner of Nicholson St and Recreation Road (Badger Creek Road).

Healesville to Gold Mining in Gobur

Not long after the family arrived in Healesville the lure of gold must have been too enticing and John moved to Gobur around 67 miles (104ks) away. Gold was discovered there in 1868 when John was 48 years old. The story of Gobur is one of ups and downs and ups and downs. Previously called Godfrey’s Creek, the renaming to Gobur caused a stir in nearby Alexandra, but the Government was insistent that all new names be native ones. Gobur, comes from the Aboriginal word “Goburra” meaning Kookaburra.[xlv]

Gobur was the location of Susan’s marriage to James CHANDLER on 27 October, 1870. According to their marriage certificate, the ceremony was conducted by Rev. Andrew Toomath, a United Church of England & Ireland clergyman and held at “Mr Hetherton’s”. This suggests the family did have a home in the township. The certificate also reveals John’s occupation as a “Miner”.

His willingness to explore another frontier, start another job, change towns and residence shows remarkable resilience and adventurousness. John may have gained gold mining experience while living in Kinlochewe where there was a minor rush in the early 1850s. If he hadn’t, I don’t think he would have been deterred anyway. He was the sort of person who grabbed opportunities as they arose beginning from the day in Ireland when he and Susannah decided to emigrate.

The Gobur Township Arises

The township sprang up when people flooded to the area after gold was discovered in Godfrey’s Creek. This was seventeen years after the first discovery of gold in Victoria. It was a new opportunity for people to get lucky and make their fortune. At first, there were only a few prospectors sleeping rough under their wagons or bark shelters. A smattering of tents dotted the stream. These early prospectors panned for alluvial gold and had some luck finding small gold nuggets near the surface of the gullies.[xlvi] By November 1868 however:

“there was a rush to peg out claims and all the ground for at least two miles downstream from the infant township was pegged out and registered without delay.”

John either worked as an individual miner, a tributer (a group of miners who worked on a contract basis with the companies for an agreed share of the gold dug up) or mine worker for a mining company. There were about 500 miners on the field in 1868 and by the end of that year, they were better off than they’d ever been or were ever going to be in the future.

A report in 2011 on the environmental history of the area said:

“Deep lead and quartz reef mining (for antimony as well as gold) rapidly began in the valleys of the Gobur and Godfrey’s creeks, leading to the establishment of a rough township consisting of the usual assortment of stores and grog shops catering to 500 or so miners. Some 1,300 ounces of gold was found in the district in three months ‘like digging spuds’ (Wylie 1995:42) and the township, a place of rough stringybark buildings, reflected a legendary masculine rip-roaringness with ‘twenty fights before noon on Saturday’ (Flett, 1970:119). Complementary to such frontier mythologising, the presence of families at Gobur is underlined by an enrolment of 43 children at the Gobur School in 1869.” [xlvii]

Henry aged 12 and Isobella aged 10, were not included on the list of children attending the school at that time.[xlviii] Perhaps Susannah stayed in Healesville with the young ones where her married daughters lived.

There were seven deep lead mines operating in the early days including the ‘Never Can Tell’, ‘Golden Gate’, ’Working Miners’, ‘Ballarat Star’, ‘Sons of Freedom’, ‘Cosmopolitan’ and ‘Dwyers Claim’. John may have worked for any one of them.

While gold was being found Gobur flourished. The number of hotels, always a good economic indicator, showed booming times with 200 hotel establishments at the end of 1869. Some however, were only in business for a year and closed their doors when gold became harder to find. It turned out most of the Gobur gold was deep and required sophisticated machinery to extract it. The gold rush for the individual prospector was soon over.

A Nasty Accident

John however still appears to be working in the area in 1874 as a well-crafted ‘Letter to the Editor’ written by John Hetherton appears in The Alexandra Times. In the letter, he thanks the Alexandra Cottage Hospital for the care and attention he received after an accident – probably a mining accident. It goes:

“Through the columns of your valuable journal, will you please grant me space to return my sincere thanks for the skilful (sic) and attentive treatment I received from Dr Fergusson while an inmate at the Alexandra Cottage Hospital, he having restored to me the use of my hand, which I expected to be deprived of through the mortification of my thumb. I also wish to express my approval of the courteous attention of the matron and the committee of the same institution. I am, &c., JOHN HETHERTON, Gobur, July 26, 1874”[xlix]

For someone who couldn’t write when he came to Australia in 1841, he could certainly put words together in 1874.

Final Days

By 1877 John was once again described as a farmer on Robert’s marriage certificate to second wife, Mary DEVERALL on 21 November 1877. And again on Henry’s marriage certificate to Mary GLENNIE on 31 January 1883 when John was 64 years old. Where he farmed is not recorded but we do know that he and Susannah spent their final days in Healesville.[l]

Susannah died on 6 June 1885, less than two years after Robert remarried. She was 66 years old and her death certificate states that she died from “hepatic” or liver disease which she had suffered for twelve months. She had been a colonist in Victoria for 44 years. Susannah is buried in the Healesville Cemetery where John also rests.

Nearly two years after Susannah’s death, John died from “Phthisis”, according to his death certificate. Phthisis is an archaic term for a “progressively wasting or consumptive condition; especially pulmonary tuberculosis”. However, John’s condition was most likely work-related ‘Miner’s Phthisis’ or ‘Silicosis’.

“Miner’s Phthisis, also known as silicosis, was a disease suffered as a result of working in underground gold mines. Its symptoms were similar to those of tuberculosis, and it was often fatal.”

The family notice of his death in The Age newspaper said:

“HETHERTON. On 6th March at Healesville after a long and painful illness, John HETHERTON aged 68 years. An old colonist of 45 years standing. Respected by all who knew him.”[lii]

You couldn’t ask for a better tribute than to be respected by all who knew you.

References

Official Records

Baptism Certificate Elizabeth Hetherton (1843-1937), 12 May 1844

Baptism Certificate Sarah Jane Hetherton (1845-1850), 28 October 1845

Baptism Certificate Susannah (1847-1933), 22 December 1847

Burial Record John Hetherton (1849-1850), Died 20 October, buried 23 October 1850

Burial Record Sarah Jane Hetherton (1845-1850), Died 26 October, buried 28 October 1850

Marriage Certificate Robert Hetherton to Jane Donnelly 14 October 1861

Birth Certificate John Hetherton, 2 August 1862 in Wangaratta (First child of Robert and Jane Donnelly)

Marriage Certificate Elizabeth Hetherton to William Chandler, 12 January 1864

Death Certificate Jane (Donnelly) Hetherton, 30 March 1864 in Connelly’s Creek (from childbirth – difficult parturition and puerperal fever)

Marriage Certificate Susan Hetherton and James Chandler, 27 October 1870

Marriage Certificate Robert Hetherton to Mary Deverall 21 November 1877

Marriage Certificate Henry Francis Hetherton to Mary Teresa Glenney, 31 January 1883

Death Certificate Susannah Hetherton (1819-1885), 6 June 1885

Death Certificate John Hetherton (1819-1887), 6 March 1887

Death Certificate Henry Francis Hetherton (1857-1891), 25 March 1891

Death Certificate Robert Hetherton (1839-1914), 29 June 1914

Death Certificate Robert John Hetherton, 30 January 1921 (Second son of Robert and Jane Donnelly)

1856 Electoral Roll – Australian Electoral Rolls 1903-1980 (Victoria, 1856, East Bourke, Whittlesea)

Ship, Strathfieldsaye Record – NSW, Australia, Assisted Passenger Lists 1828-1896 http://indexes.records.nsw.gov.au/ebook/list.aspx?series=NRS5316&item=4_4814&ship=Strathfieldsaye

Books, Journals and Academic Papers

Chuk, Florence The Somerset Years, Pennard Hill Publications, Ballarat Vic., 1987

Wright, Clare The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka, Text Publishing, Melbourne, Australia 2014, p. 175

Hagger, Jennifer Australian Colonial Medicine, Rigby, 1979

Waghorn, John F & Hulley, Pat – Gobur and the golden gate, 1982 John F Waghorn, Thomastown, Vic

Healesville and District Historical Society, Images of Time – A Pictorial History of Healesville – From a Village to a Town, Volume 1 1864 –1920, Northeast Publishing & Roda Graphics Australia Pty Ltd, Kinglake, Vic., 2013

‘The Merriang Road – It’s Discovery and Development (1824-1860’s), The Victorian Historical Magazine, Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria, 184th Issue, Vol. 38, May 1964, No. 2

Curran, Daragh, A Society in Transition: The Protestant Community in Tyrone 1836-42, PH.D Thesis, Department of History, National University of Ireland, September 2010 http://eprints.maynoothuniversity.ie/2588/1/DC_thesis.pdf

Websites

http://eprints.maynoothuniversity.ie/2588/1/DC_thesis.pdf

http://www.angelfire.com/al/aslc/immigration.html – Australia’s Early Immigration Schemes, A Barnes reprinted from ‘Tulle’, Vol 17, No. 2.

Audio Transcript of Dr Perry McIntyre, historian and genealogist, in a series of talks on Irish Immigration to Australia held at the National Museum of Australia in 2011. http://www.nma.gov.au/audio/transcripts/NMA_Mcintyre_20110629.html

www.fairhall.id.au/resources/journey.html compiled by Bruce Fairhall adapted from an article by Philip Bowden Mitchell, The Benedum Bowdens, Magenta Press 1988

http://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/disaster/pandemic/display/95617-%22ticonderoga%22-deaths

http://rootsweb.ancestry.com The Development and Control of the Bounty System 1835-1841 Chapter VIII of Immigration into Eastern Australia 1788-1851, R B Madgwick, Longmans, Green & Co 1937. Information provided by Peter Mayberry, Tuggeranong ACT on 15 April, 2004

http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/AUS-VIC/2001-09/0999844570

http://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/3321/download-report

Cited as (Hopton 1951) in a Victorian Heritage Database Report “Batman Pastoral Run Northern Hut, Former Kinlochewe Township”

http://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/3321/download-report

City of Whittlesea Heritage Study © 1990 Meredith Gould Architects Pty Ltd p.77 https://www.whittlesea.vic.gov.au/media/1762/city-of-whittlesea-heritage-study-1990.pdf

David Moloney, A True Survivor – John Batman’s Outstations, Victoria News Aug 2010, http://www.nationaltrust.org.au

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Thursday_bushfires

http://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM00473b.htm

CHIG Bushfires of Black Thursday 1851 – When Smoke Turned Day into Night, http://www.chig.asn.au

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merri_Creek

http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/AUS-VIC-HIGH-COUNTRY/2002-03/1017311228

Context, Thematic Environmental History Final Revised Report July 2011 – Murrindindi Shire Heritage Study Stage 1 (Vol 1), Context Pty Ltd, Brunswick 2011 www.murrindindi.vic.gov.au/…/heritage-study/heritage-study-vol-1-thematic-history

Craigieburn Historical Interest Group http://www.chig.asn.au

http://www.irish-genealogy-toolkit.com/Irish-names.html

https://researchdata.ands.org.au/journal-miners-phthisis-allowance/152797?source=suggested_datasets

Newspapers of the day accessed on www.nla.gov.au/trove

Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian

The Weekly Times

The Argus

Healesville Guardian

Port Phillip Patriot & Morning Advertiser

Alexandra Times

The Age

Maps

Crown allotments 10 & 11 on Map KALKALLO No. 19 – Merriang BIB: 12995543

Citations and Notes

[i] How could you read but not write? I asked this question at an Irish Special Interest Group meeting at the Heraldry and Genealogy Society of Canberra (HAGSOC) and a member of the group claimed that learning to read was given more emphasis than learning to write in that period because it was considered important that people be able to read the Bible.

[ii] County Tyrone was listed on the Ship’s records as the place where they came from and it was used consistently on other records in Australia as well.

[iii] The Griffiths Valuation (GV) was a land survey commissioned by the Government and conducted by Sir Richard Griffiths, the Director of the Valuation Office in Dublin, between 1847-1864. The purpose of the GV was to provide a starting point for the Government to bring uniformity into the determination of taxes to help support the poor. It was also called a Primary Valuation of Ireland. All privately owned lands and buildings in both rural and urban areas were valued to work out a rental rate for each property. The GV is an invaluable source for family historians as it provides information on tenants, landlords and the extent of property owned or tenanted even though it only identifies heads of households, not the entire household.

[iv] The Weekly Times, Saturday 20 June 1885

[v] http://www.askaboutireland.ie/griffith-valuation/index.xml?action=doNameSearch&Submit.x=31&Submit.y=15&Submit=Submit&familyname=hetherton&firstname=Robert&baronyname=&countyname=&unionname=&parishname=

[vi] Death certificates can be troublesome documents with variations in facts. It depends on the knowledge of the informants.

[vii] Quote is from the 1835 Poor Enquiry 6:67 Appendix E cited in Daragh Curran’s PH.D Thesis, A Society in Transition: The Protestant Community In Tyrone 1836-42. This thesis provided me with most of the quotes and information about the Ireland that John and Susannah left behind.

[viii] In early 1600’s at the time of the Ulster Plantation, Sir Richard Wingfield, later Viscount Powerscourt, was granted 9,000 acres of land in and around Benburb, including the village in recognition of his services to the British Crown. The Wingfield/Powerscourt family were also granted another estate near Enniskerry, Co. Wicktown where they mainly lived and where the Powerscourt Estate still exists. http://www.servitelibrary.org/#!about-us/c8xt